A Key Fed Official Says the Job Market is Just Fine. But is He Right?

Money is not a client of any investment adviser featured on this page. The information provided on this page is for educational purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. Money does not offer advisory services.

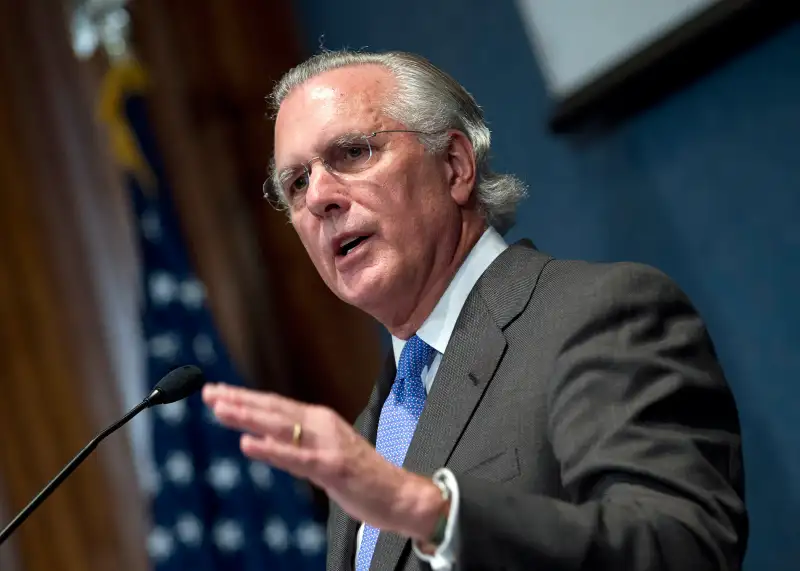

In between references to Shakespeare, beer goggles and Wild Turkey, Dallas Federal Reserve Bank President Richard Fisher— a member of the Federal Open Market Committee that sets the nation's interest-rate policy— expressed concern Wednesday about the risks caused by the Fed's ongoing stimulative policies.

Thanks to a dramatically improving jobs picture, according to Fisher, the Fed should not only cut off its bond-purchasing program (known as "QE3") by October, but the central bank should also shrink its portfolio of assets and begin raising interest rates early next year or sooner.

Whether or not the economy can withstand monetary tightening — fewer jobs means fewer people able to buy stuff — is open for debate. The real question, though, is if the jobs picture is really that strong?

First some context.

In his colorful speech, Fisher, one of the Fed's leading "inflation hawks," reiterated his belief that the Fed’s rapidly escalating balance sheet (now at approximately $4.4 trillion) in combination with a near-zero federal funds rate has led to investors having “beer goggles.” (As Fisher explains it, “this phenomenon occurs when alcohol renders alluring what might otherwise appear less clever or attractive.”) This is what he says is happening with stocks and bonds, which are both relatively expensive.

To make his point Fischer quoted Shakespeare’s Portia in Merchant of Venice: “O love be moderate, allay thy ecstasy. In measure rain thy joy. Scant this excess. I feel too much thy blessing. Make it less. For fear I surfeit.”

Portia’s adjectives (joy, ecstasy and excess) describe “the current status of the credit, equity and other trading markets that have felt the blessing of near-zero cost of funds and the abundant rain of money made possible by the Fed and other central banks that have followed in our footsteps,” Fisher said.

Of course, the Federal Reserve hasn’t bought trillions of dollars of debt, and cut the main interest rate to nothing, for no reason. There was something called, you know, the Great Recession — the once-in-a-lifetime cataclysmic economic event from which the country is still recovering.

But, said Fisher, things are improving, especially in the labor market. Not only did businesses add almost 300,000 employees last month, but there are more job openings, workers are quitting more often and wages are rising. Is he right?

Let’s check out some graphs:

Job openings:

Fisher is right that job openings “are trending sharply higher.” This time last year, there were a little less than 3.9 million job openings. Right now there are more than 4.6 million – an 18% increase.

"Quits":

The healthier an economy, the higher the number of employees who quit their job to either find another or start a new business. Therefore a higher so-called quits rate, means a healthier labor market.

Like job openings, the number of quits has been rising since bottoming out during the recession. The major difference though is that the number of job openings has almost reached pre-recession levels, while quits has not.

Wages:

Fisher admits that wages aren’t growing “dramatically.” Nevertheless, he cites the Current Population Survey and the most recent National Federation of Independent Business survey to show that wages are on the rise.

However, wage data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that Americans in the private sector are earning $24.45 an hour, only up 1.9% from last year.

But these three metrics aren’t the only metrics to gauge the health of the labor market.

Long-Term Unemployed:

Before the recession, about 1.3 million workers were without a job for longer than 27 weeks. Today, that number is slightly more than 3 million. While that’s significantly better than the post-recession high of 6.8 million in August 2010, there are still a lot of workers who’ve been without a job for a long time.

“Long-term unemployment is still a significant source of slack in the economy and is accounting for a historically large share of the total unemployment rate,” says Wells Fargo Securities economist Sarah House.

Broader unemployment:

And while the unemployment rate may signify the economy is moving closer to full employment, the picture is less sanguine if you look at a broader unemployment rate that takes into account the underemployed (part-time workers who want to work full-time) and discouraged workers. Before the recession that number hovered a little over 8%. It’s now 12.1%. And while it’s trending down, it’s not coming down fast enough. At least according to recent testimony by Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen.

Conventional wisdom says inflation will come when wages really start to rise. Some, like Fisher, think we're getting really close to that point. But if you take into account wage data from the BLS and look at the millions of Americans who aren't working to their full capacity, it's not hard to see how tightening monetary policy might make life harder on lots of workers.