Why 'America's Team' Home Games Are Dominated by Visiting Team Fans

This Sunday, the Dallas Cowboys head to Seattle to face the Seahawks. Not only are Russell Wilson, Richard Sherman, and company the Super Bowl champions, they also play at CenturyLink Field, one of the NFL's loudest stadiums, a venue that's been given some of the credit for the Seahawks' overwhelming dominance at home games.

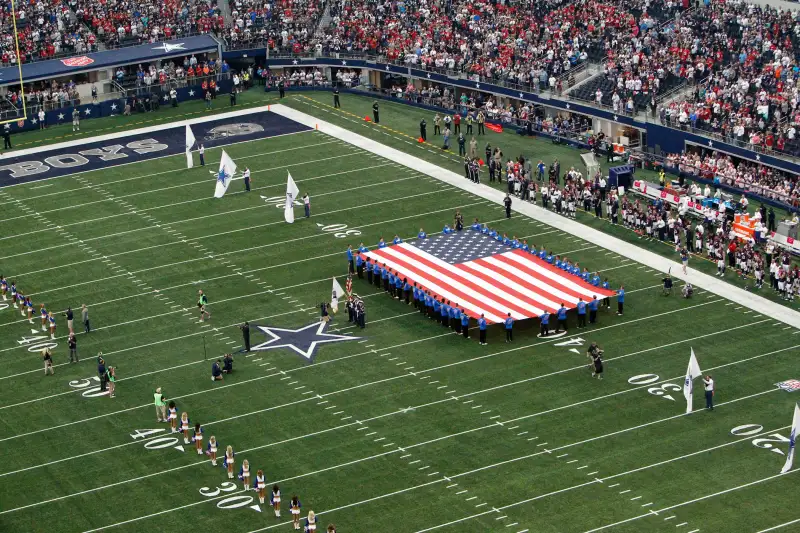

While the Seahawks are bejeweled with Super Bowl rings, the Cowboys, a.k.a. "America's Team," still try to stake their claim as the more popular franchise, and the squad also has bragging rights for playing in the more celebrated stadium. With a gargantuan 160-foot-long screen above the field, seating capacity for 80,000 fans, and a Super Bowl and NCAA Final Four already under its belt, AT&T Stadium has been an unabashed phenomenon since it opened five years ago.

What the stadium hasn't delivered lately, however, is any real home field advantage for the Cowboys. Quite the opposite, in fact.

The Cowboys have hosted three home games thus far in the 2014 season, and at all three an estimated 40% of the seats have been occupied by the opposing team's fans. Dallas Morning Star columnist Tim Cowlishaw described the situation as the "biggest home-field disadvantage in the NFL" after the Cowboys barely eked out a home victory this past weekend over the visiting Houston Texans. “Today we played on the road," Cowboys quarterback Tony Romo said after the game on his team's own home turf. "We had to go to a silent count, and that was the first time I had to do that throughout the game at home.”

Who and what is to blame for this scenario? The discussion must start with the astronomical costs of attending NFL games nowadays. Taking a family of four to a Dallas Cowboys home game is estimated to run $634.80, and the average price of non-premium seats at the stadium is over $100.

As prices for tickets, parking, food, and other extras at NFL stadiums have soared, the fan base has shifted, with more seats being snatched up by corporations and wealthy types who, let's be honest, aren't the diehard fans of yore. These "fans" are less likely to feel compelled to attend every game in their season-ticket package, and the ease of using secondary market resale sites like StubHub helps them sell unwanted tickets. Add in that "America's Team" boasts season ticketholders who live far away in neighboring states and even Mexico, that the stadium is one of the league's biggest, and that the venue is considered a bucket-list "destination" for sports fans, and it's easy to see how tens of thousands of Cowboys tickets go up for resale before every home game—and how they're promptly snatched up by fans of the Saints, 49ers, or whatever other visiting team is in Dallas that week.

Mark Cuban, the outspoken owner of the NBA's Dallas Mavericks, feels sorry for his fellow pro sports owner in Dallas. "Part of having to pay for a $1.2 billion building is [high] ticket prices," Cuban said to the Morning News. "You got to sell those tickets. That’s just what happens. So I do feel bad for him." As for the idea of a visiting team's fans outcheering the home team's loyalists, Cuban said, "It would drive me nuts."

For the many sports fans who hate the Cowboys for their long history of questionable ethics and consider Jerry Jones to be obnoxious and arrogant if not worse (he was accused of sexual assault last month), the current "home field disadvantage" scenario plays out like a morality tale. In it, Jones is righteously being punished for greed, excessive pride, and overshooting his bounds, not unlike the story of Icarus or the Tower of Babel. It's bad karma come home to roost.

As for Jones himself, he said this week that he understands why Cowboys ticketholders put their seats up for sale, and he doesn't think it's a big problem. "They go out into the market and they sell their tickets and get that money," Jones said to a Dallas radio station this week. "In doing so, they really do reduce their overall cost of coming to the stadium considerably because you sell two or three games as a season ticket holder and you’ve just about recouped what you’ve spent to buy the ticket."

You see, it all comes down to money. No wonder Jones understands their motivation so well.