The Senate Health Care Bill Could Hurt You Even If You Get Insurance Through Work, Report Says

At least 20 million Americans with employer-provided health insurance could find themselves one devastating accident or diagnosis away from financial ruin if the Senate health care bill is passed as expected, according to a report released Thursday by the Center for American Progress.

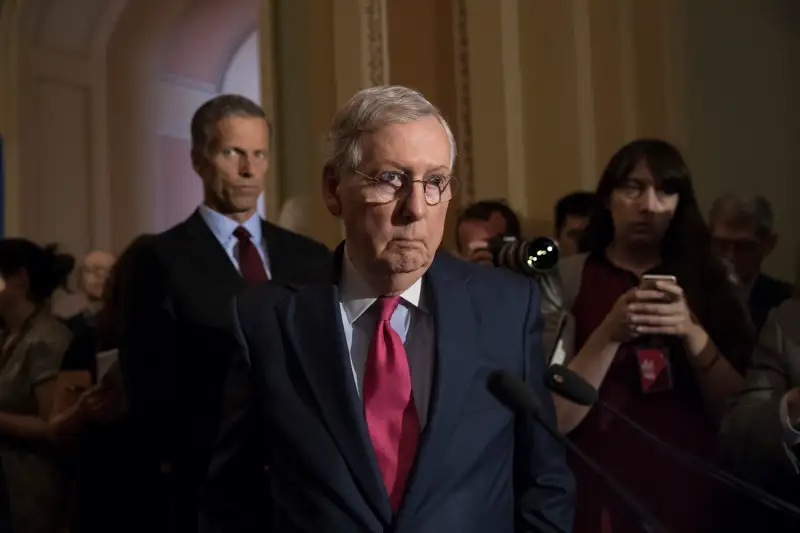

Lawmakers have been working behind closed doors on their American Care Act (ACA) replacement bill, whose primary focus is reshaping the individual insurance market and rolling back the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid. Yet the bill may also include a provision that would weaken protections for millions of Americans with employer-sponsored health coverage, Axios reports.

Senators haven’t released a draft of their legislation, and media reports have said they don’t intend to ahead of a vote that could happen before Congress breaks for July 4. The Center for American Progress assumed that the bill would include a waiver provision that could weaken patient protections and used survey and census data to estimate the number of workers and dependents in large company plans who would be affected.

The waiver was also included in the House version of the health care bill, the American Health Care Act, which passed on May 4.

This provision would allow employers to bring back annual and lifetime caps on health coverage. In 2009, before the ACA, 59% of workers with employer-provided health insurance were in a plan with a lifetime limit on how much the plan would cover. That cap could be set as low as $1 million, which wouldn’t be hard for certain patients to hit. For example, a baby who spent months in the neonatal intensive care unit or someone who was born with hemophilia, developed an aggressive form of cancer, or got paralyzed in a car accident would all easily reach that sum.

Once a person hit his lifetime cap, the health plan would stop paying his expenses. Someone who hit his annual cap would have to wait until the following year for coverage. “To a lot of people, it probably came as a surprise,” says Emily Gee, a health economist at the left-leaning Center for American Progress and co-author of the report.

The Senate bill could expose workers to these caps by allowing states to apply for a waiver to define their own list of essential health benefits. The Affordable Care Act required most plans to include a robust list of 10 essential benefits, including prescription drug coverage, mental health and maternity care. The law banned annual and lifetime limits for essential health benefits, which in effect meant that most care wasn’t subject to any caps.

But if states could pick and choose their essential health benefits, then employers could do the same, bringing back caps for any care that doesn’t fall under their new definition of "essential." Individual and small group (generally, under 50 workers) plans in a particular state would be bound by their local regulations—so if their state mandated a full slate of essential health benefits, then they wouldn’t have the option of choosing a health plan that excluded one.

By contrast, regulations allow large employers to base their benefit structure on any given state’s. Since essential health benefits are standard under the Affordable Care Act, this ability isn’t currently that meaningful. However, if variations in essential health benefits become the norm, then employers that want to cut health costs could gravitate toward the state that offers them the most flexibility to do so.

To be sure, not all large employers will choose to set caps. Plenty of companies see comprehensive health insurance as a way to attract and keep talented employees, says Zack Pace, senior vice president of CBIZ, a benefits consulting firm. But the relentlessly rising cost of medical care and prescription drugs means that some firms may have no choice but to limit their workers’ coverage, Gee says.

The Center for American Progress based its estimates on a survey by Willis Towers Watson in which 20% of large employers said they would impost annual limits and 15% would impose lifetime limits if the ACA protections were repealed. Authors then used U.S. Census data to estimate the number of large-company workers and their dependents who would be affected: nearly 27 million would be subject to annual limits, and about 20 million would be subject to lifetime limits.

This worries advocates for people with pre-existing conditions. “Imagine being the individual in active cancer treatment,” says Anna Howard, principal in policy development at the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, “and being told that, in effect, ‘we’re not going to be paying for the products and services that are keeping you alive.’”