Money Classic: Teaching Kids How to Budget (1981)

Money is turning 50! To celebrate, we’ve combed through decades of our print magazines to uncover hidden gems, fascinating stories and vintage personal finance tips that have (surprisingly) withstood the test of time. Throughout 2022, we’ll be sharing our favorite finds in Money Classic, a special limited-edition newsletter that goes out twice a month.

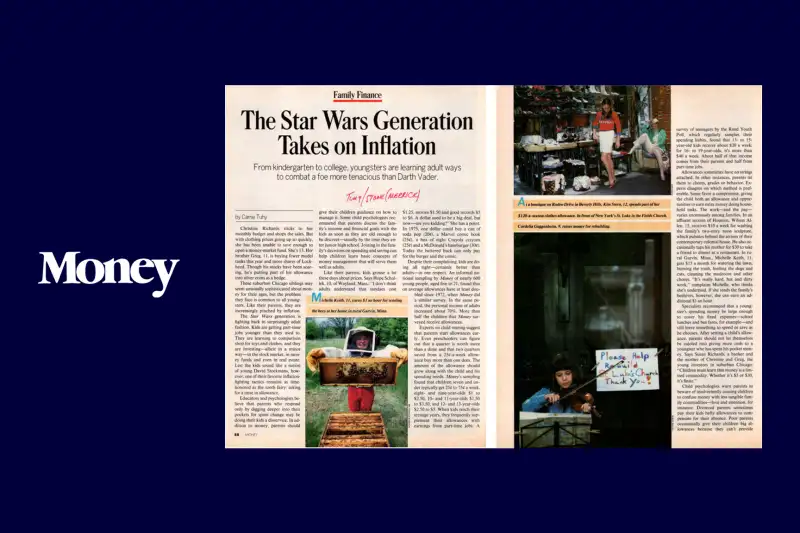

This excerpt, featured in the 22nd issue of Money Classic, comes from a story in our April 1981 edition.

Christine Richards sticks to her monthly budget and shops the sales. But with clothing prices going up so quickly, she has been unable to save enough to open a money-market fund. She's 13. Her brother Greg, 11, is buying fewer model tanks this year and more shares of Lockheed. Though his stocks have been soaring, he's putting part of his allowance into silver coins as a hedge.

These suburban Chicago siblings may seem unusually sophisticated about money for their ages, but the problem they face is common to all youngsters. Like their parents, they are increasingly pinched by inflation.

The Star Wars generation is fighting back in surprisingly adult fashion. Kids are getting part-time jobs younger than they used to. They are learning to comparison shop for toys and clothes, and they are investing — albeit in a minor way — in the stock market, in money funds and even in real estate. Lest the kids sound like a nation of young David Stockmans, however, one of their favorite inflation-fighting tactics remains as time-honored as the tooth fairy: asking for a raise in allowance.

Educators and psychologists believe that parents who respond only by digging deeper into their pockets for spare change may be doing their kids a disservice. In addition to money, parents should give their children guidance on how to manage it. Some child psychologists recommend that parents discuss the family's income and financial goals with the kids as soon as they are old enough to be discreet — usually by the time they enter junior high school. Joining in the family's decisions on spending and saving can help children learn basic concepts of money management that will serve them as well as adults.

Like their parents, kids grouse a lot these days about prices. Says Hope Schalek, 10, of Wayland, Mass.: "I don't think adults understand that sundaes cost $1.25, movies $1.50 and good records $5 to $6. A dollar used to be a big deal, but now — are you kidding?" She has a point. In 1975, one dollar could buy a can of soda pop (20¢), a Marvel comic book (25¢), a box of eight Crayola crayons (25¢) and a McDonald's hamburger (30¢). Today the battered buck can only pay for the burger and the comic.

Despite their complaining, kids are doing all right — certainly better than adults — in one respect. An informal national sampling by Money of nearly 600 young people, aged five to 21, found that on average allowances have at least doubled since 1972, when Money did a similar survey. In the same period, the personal income of adults increased about 70%. More than half the children that Money surveyed receive allowances.

Experts on child rearing suggest that parents start allowances early. Even preschoolers can figure out that a quarter is worth more than a dime and that two quarters saved from a 25¢-a-week allowance buy more than one does. The amount of the allowance should grow along with the child and his spending needs. Money's sampling found that children seven and under typically get 25¢ to 75¢ a week, eight- and nine-year-olds $1 to $2.50, 10- and 11-year-olds $1.50 to $3.50, and 12- and 13-year-olds $2.50 to $5. When kids reach their teenage years, they frequently supplement their allowances with earnings from part-time jobs. A survey of teenagers by the Rand Youth Poll, which regularly samples their spending habits, found that 13- to 15-year-old kids receive about $20 a week; for 16- to 19-year-olds, it's more than $40 a week. About half of that income comes from their parents and half from part-time jobs.

Allowances sometimes have no strings attached. In other instances, parents tie them to chores, grades or behavior. Experts disagree on which method is preferable. Some favor a compromise, giving the child both an allowance and opportunities to earn extra money doing household tasks. The work — and the pay — varies enormously among families. In an affluent section of Houston, Wilson Allen, 15, receives $10 a week for washing the family's two-story neon sculpture, which pulsates behind the atrium of their contemporary colonial house. He also occasionally taps his mother for $30 to take a friend to dinner at a restaurant. In rural Garvin, Minn., Michelle Keith, 11, gets $15 a month for watering the lawn, burning the trash, feeding the dogs and cats, cleaning the mudroom and other chores. "It's really hard, hot and dirty work," complains Michelle, who thinks she's underpaid. If she tends the family's beehives, however, she can earn an additional $1 an hour.

Specialists recommend that a youngster's spending money be large enough to cover his fixed expenses — school lunches and bus fares, for example — and still leave something to spend or save as he chooses. After setting a child's allowance, parents should not let themselves be cajoled into giving more cash to a youngster who has spent his pocket money. Says Susan Richards, a banker and the mother of Christine and Greg, the young investors in suburban Chicago: "Children must learn that money is a limited commodity. Whether it's $5 or $30, it's finite."