Several of the Biggest Pharma Giants Are Freezing Drug Prices. Here's How It Will Affect You

You may have been hearing a flurry of news about drug price freezes recently — but don't start spending your windfall just yet.

Bowing to political pressure from the White House, some of the biggest drug manufacturers have announced a series of temporary price freezes or even price cuts to their medications in recent weeks. Yet it’s unlikely these moves will translate into lower out-of-pocket costs for consumers, experts say.

Pfizer, Novartis, and Bayer are among the major drug companies that announced they would not seek any price increases to their drugs for the rest of the year — and Merck was among those that promised to actually lower prices on certain drugs.

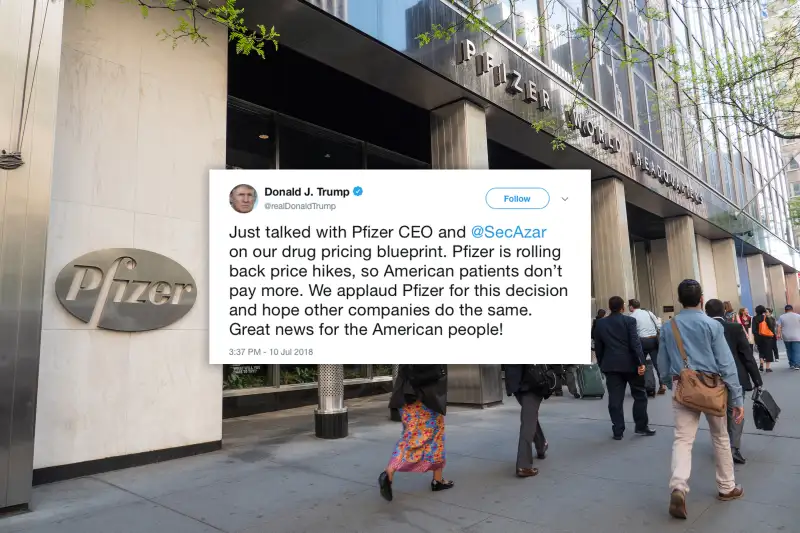

President Donald J. Trump, who has made lowering drug costs a priority, tweeted his thanks to the companies.

Yet patients expecting relief from sky-high prices will likely be disappointed. “It does seem more like a PR type of thing than anything that has a meaningful impact on the patient,” says Leigh Purvis, director of health services research in the AARP Public Policy Institute.

For starters, your bill at the pharmacy counter depends in part on your diagnosis. Conditions such as high cholesterol, high blood pressure and depression can generally be treated with low-cost generic drugs; those are unlikely to be affected by the latest round of announcements. The drugs that make headlines are usually pricey, brand-name treatments for diseases like cancer, diabetes, and rheumatoid arthritis — conditions for which there are no low-cost alternatives.

Then there's the time frame of the price freezes. As it currently stands, most of the drug makers have put the brakes on only through the end of the year. But Big Pharma often raises prices in January, and then at various points throughout the year, depending on the drug, Purvis says. So while prices may not increase for the next five months, for many medications they’ve been frozen at an already high level — and could rise again at the beginning of 2019.

A survey of about 3,000 brand-name prescription drugs found that more than 60 doubled in price, and 20 quadrupled, between December 2014 and early February 2016, according to Connecture, a health care technology firm.

Take Gleevec, a cancer drug by Novartis that ranked 25th among the top 200 prescription drugs in 2016 by global sales, according to Connecture. Gleevec’s price will be frozen, but it had already hit $140,000 a year by 2017, according to David Mitchell, founder and president of Patients for Affordable Drugs, a nonprofit advocacy organization.

“It’s hard to give drug companies credit for keeping prices high,” says Mitchell, a cancer patient himself who has experienced high drug costs first-hand.

And some of the drug price changes may simply have limited impact. Merck announced it would lower prices on Zepatier, its treatment for Hepatitis C, by 60%, for instance, as well as cutting costs on several other medications by 10%. But Zepatier itself was a late entrant into the market with very lackluster sales, says Jim Yocum, senior vice president of federal programs at Connecture — so the Zepatier cut won’t really affect either patients or the company’s bottom line.

Who Pays the Price?

Finally, there's one other issue to consider: the role that insurance companies play.

Patients without insurance are usually the only ones who pay a drug’s list price. For everyone else, what you pay for drugs depends on the deals negotiated for your insurer by pharmacy benefit managers, companies that act as middlemen between the drug makers and health plans.

Even if the recently announced drug price freezes or cuts translate into some savings for insurers, it’s not at all a given that insurers will pass along those savings directly to patients taking that particular drug, Purvis cautions.

For starters, many health plans don’t make changes to their formulary — that’s their list of covered drugs and pricing schemes — mid-year.

And even if your drug is getting a price cut, insurers could choose to pass savings along more broadly next year, by limiting price hikes for all covered consumers, Purvis says. That's because insurers usually pass high drug costs on to customers in the form of higher copayments, coinsurance, premiums and deductibles. So while more modest price increases for your medications could benefit everyone on your plan, they won't necessarily mean a huge change for you, Purvis notes.

Experts argue that — rather than relying on one-off actions by manufacturers — the health care system actually needs structural changes to meaningfully lower drug prices.

In the spring, President Trump released a blueprint on lowering drug prices; proposals included requiring manufacturers to include list prices in direct-to-consumer advertising and giving Medicare Part D plans more power to negotiate with manufacturers.

The recent price freeze announcements could be drug companies’ way of signaling that they’ve heard the Trump administration's message, and that they’re willing to work together. “The timing is not an accident,” Yocum says.