What the End of Net Neutrality Means for You

Net neutrality as we’ve known it is over. The Federal Communications Commission voted on Thursday to repeal rules over how Internet service providers, or ISPs, grant online access. And the change could have significant consequences for your Internet use—and its costs.

If you’re wondering what exactly net neutrality is and how it will affect your monthly bill, a quick rundown: Net neutrality refers to the principle that ISPs must treat all digital content equally, whatever it is and wherever it’s hosted. So broadband companies such as AT&T and Comcast can’t privilege the loading of one website over another, and they can’t charge users more to view certain material—like, say, streaming movies.

This is what’s known as the open Internet.

The FCC put into place net neutrality regulations in 2015, following the recommendation of President Barack Obama. The federal government thereby classified internet as a public utility, under Title II Order of the 1934 Communications Act, treating it the same way as phone service or electricity.

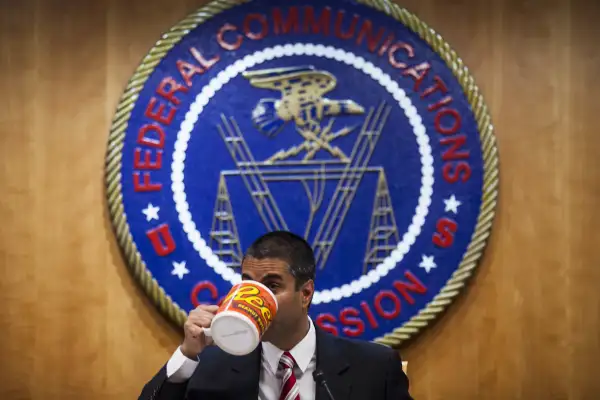

Things have shifted under President Donald Trump. Current FCC chairman Ajit Pai, appointed by Trump, endorsed the repeal of net neutrality before the vote, based on the belief that it will nurture competition. He decided in its favor alongside his fellow Republican commissioners, resulting in a 3-2 split.

What does that mean for you? It’s still early to say. New rules won’t go into effect for weeks, so it may look as if all is normal right now. And many factors are still up in the air. But the transition opens up numerous possibilities for how you get online and what it costs.

Bundling the Internet

Net neutrality supporters argue that the deregulation will result in different internet packages that prioritize certain kinds of content. Broadband companies could offer bundles, much in the same way as cable companies. So if you love going on Twitter and Facebook, you could pay for one kind of subscription. And if you binge-watch Netflix or Hulu, you could instead pay for a video-oriented package.

And if you want it all, you may have to pay a lot more. In the same vein of premium cable bundles that give you every channel possible, ISPs could offer deluxe options. Critics believe this would unfairly benefit higher-income households at a time when internet communication is crucial.

Meanwhile, ISPs could downgrade the speed of content providers not seen as worthy enough, a practice known as throttling.

Without government protections, consumers would be "paying more money to their internet companies to get a less diverse, less interesting [internet]," said Evan Greer, the campaign director of Fight for the Future, a nonprofit focusing on digital rights.

The Fast Lane vs. the Slow Lane

There’s another way web access could be split up. Internet plans already cap data and charge more for higher bandwidth limits (the rates at which you can upload and download). But providers were previously prohibited from prioritizing any particular corner of the web, as long as it’s legal.

Without rules barring paid prioritization, say critics of the FCC’s move, broadband companies could create fast lanes and slow lanes for different sources of content. Technology giants like Google, Facebook, and Netflix could pay a hefty fee to deliver their content more rapidly to consumers; content from startups that lack the money to do so could wind up in the slow lane.

Such a structure would provide new revenue for ISPs. Meanwhile, a smaller streaming company competing against Netflix would be at a huge disadvantage. Many consumers may end up sticking to larger, more widely available sources.

Small businesses and consumer groups have already voiced concerns that without net neutrality, the bigger players will have an edge. If, for example, you’re self-employed and sell your woodwork on a personal website, you may lose out.

Theoretically, ISPs that also own media entities would be able to give free rein to their own content, giving it a market advantage. So if you subscribe to AT&T, its video could suddenly look much better than YouTube's. This is particularly relevant in an era of big media mergers such as Comcast’s with NBCUniversal and AT&T's planned deal with Time Warner.

Even some larger tech companies like Netflix and Twitter have argued against the repeal. Both called the FCC’s plan “misguided,” claiming that net neutrality helps innovators and Internet users more generally. Netflix, after all, was once a little-known startup.

Blocking Your Way

Those against the repeal also worry about outright censorship. Experts have said that broadband companies will now be able to stifle certain political ideas.

They could also simply wipe out competition. Public interest organizations cited an example in which AT&T allegedly violated net neutrality regulations by blocking certain iPhone and iPad users from using FaceTime, which is perceived as a threat to traditional telecommunication.

Maybe Nothing Will Change

There’s still a lot of uncertainty in the FCC’s decision. The debate, as with so much policy, is more complex than it may seem at first glance.

Brendan Carr, a Republican FCC commissioner, described critics’ scenarios as “apocalyptic.” Pai said he thinks the new rules will force ISPs to be more “transparent” about their practices, expanding consumers’ choice.

“Did these fast lanes and slow lanes exist? No,” the chairman said in a speech earlier this year. “It’s almost as if the special interests pushing Title II weren’t trying to solve a real problem but instead looking for an excuse to achieve their longstanding goal of forcing the Internet under the federal government’s control.”

Many organizations representing both consumers and Internet companies vehemently disagree. Public Knowledge and the National Hispanic Media Coalition promised to file lawsuits against the reversal. The Internet Association, a lobbying group that works on behalf of tech behemoths like Google and Facebook, said it was also considering litigation. Critics have pointed out that the average American has only one or two options for ISPs, circumscribing the kind of true competition Pai praises.

Politicians also quickly jumped into the fight following Thursday’s vote. New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman guaranteed legal action to stop the change, as did Washington State Attorney General Bob Ferguson, and Democratic lawmakers have called for a bill that would put back into effect the oversight that the FCC stripped away.

The broadband companies, for their part, have a slightly different take. Both AT&T and Verizon have issued statements in support of a free Internet, but assert that the previous regulations were overly broad. Several providers have recently pledged not to block or throttle service even without the old rules.

Whether they'll keep their word remains to be seen.