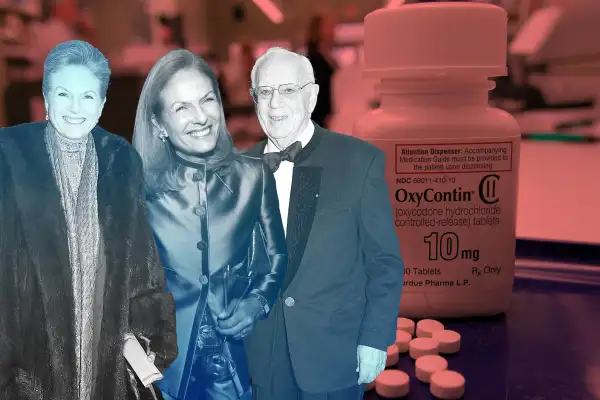

The Billionaires Behind OxyContin Are Being Sued Over the Opioid Crisis. Here's What We Know About the Sackler Family's Money

Some of the country's biggest pharmaceutical companies need to be held responsible for the deadly opioid crisis that has plagued the U.S. for over two decades, recently filed high-profile lawsuits allege.

And one family in particular is increasingly in the crosshairs — the Sacklers, who are the principal owners of Purdue Pharma, the maker of the popular (and addictive) prescription painkiller OxyContin.

Last week, New York Attorney General Letitia James filed a lawsuit against six prescription opioid manufacturers and four prescription drug distributors, as well as specific members of the Sackler family, for "causing widespread addiction, overdose deaths, and suffering."

Last summer, Maura Healey, Massachusetts' attorney general, launched a lawsuit against Purdue Pharma and 16 company executives and board members, including at least eight members of the Sackler family. "Purdue Pharma and its executives built a multi-billion-dollar business based on deception and addiction," Healey said. "The more drugs they sold, the more money they made, and the more people in Massachusetts suffered and died."

Purdue Pharma is based in Connecticut, and the state attorney general there has also filed a lawsuit against the firm and the Sacklers, alleging that the defendants “misinformed patients and doctors to get more and more people on Purdue’s dangerous drugs.”

The term opioids can apply to illegal opium-based drugs like heroin, as well as brand-name pain relievers sold under legal prescription such as Vicodin, Percocet, and OxyContin. Nearly 218,000 people in the U.S. died from prescription opioid overdoses from 1999 to 2017, according to the CDC, and the rate of prescription opioid-related deaths in 2017 was five times higher than in 1999.

OxyContin has been one of the most profitable and aggressively marketed opioids, and some 2,000 lawsuits have been filed against the company that makes it, Purdue Pharma. Some of the lawsuits single out not just Purdue Pharma but its wealthy owners. The Sacklers have been named to Forbes' list of richest families with a collective net worth of $13 billion — and they received over $4 billion from Purdue Pharma between 2008 and 2016, Massachusetts Attorney General Healey claims.

Purdue Pharma and Sackler family representatives have broadly denied the claims, arguing that they are being unfairly vilified and singled out in opioid lawsuits. Purdue Pharma points out that it has spent millions on education and research to help alleviate the opioid crisis. A statement from the Sackler family provided to the New York Times said that the Massachusetts and New York lawsuits are “filled with claims that are demonstrably false and unsupportable by the actual facts.”

The Sacklers and other current and former Purdue board members made a motion this week to dismiss the Massachusetts lawsuit, saying that they “did exactly what one would expect of directors of a company," and that the suit “fails to specify how any individual director, much less all of them, personally engaged in unlawful promotion of prescription opioids or instructed anyone else to do so,” according to the Wall Street Journal.

Who are the Sacklers, and what is their role in the creation and promotion of OxyContin? For decades, the Sackler family was known best for their philanthropy and multi-million-dollar donations to support the arts and schools like the University of Connecticut and Yale University. The Sackler name graces special wings and galleries of more than a dozen museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City and the Louvre in Paris.

Yet as the New Yorker story from 2017 explained, "while the Sacklers are interviewed regularly on the subject of their generosity, they almost never speak publicly about the family business, Purdue Pharma."

Lately, even the cultural institutions that have benefited greatly from the Sacklers' generosity have distanced themselves from the family. Among the museums to recently refuse donations from the Sacklers due to their ties to OxyContin and the opioid crisis are the Guggenheim Museum in New York City and the Tate museums and the National Portrait Gallery in London.

Andrew Kolodny, the co-director of the Opioid Policy Research Collaboration at Brandeis University, told the Hartford Courant that is unconscionable for any politician, museum, college, hospital, or other institution to keep gifts presented by the Sacklers: "It’s blood money and it should be returned," he said.

Here's what we know about the wealth of the elusive Sackler family — how they made their riches, their relationships with OxyContin and Purdue Pharma, and why they are being targeted in opioid crisis investigations.

The Sacklers and Purdue Pharma

The company that became Purdue Pharma was a small, struggling New York drugmaker when it was purchased in 1952 by Arthur Sackler and his two brothers, Raymond and Mortimer. The Sackler brothers were born in Brooklyn to Jewish immigrant parents and came of age during the Great Depression. All three were medical doctors, and though the original brothers have all passed away, Purdue Pharma is still a private company owned by their descendants.

Arthur Sackler died in 1987, years before Purdue Pharma developed and marketed OxyContin, which received FDA approval in 1995. A year ago, Arthur's widow, Jillian Sackler, felt compelled to release a statement affirming that "none of the charitable donations made by Arthur prior to his death, nor that I made on his behalf after his death, were funded by the production, distribution or sale of OxyContin or other revenue from Purdue Pharma. Period."

But chroniclers of America's opioid crisis say that Arthur Sackler played an enormous part in his family's success in the pharmaceutical industry, and the innovative strategies he employed for prescription drug marketing were critical to the rise of OxyContin, which hit $1.6 billion in sales by 2003. Barry Meier, the author of Pain Killer: An Empire of Deceit and the Origin of America's Opioid Epidemic, called Arthur Sackler "the godfather of the modern-day drug-advertising industry," noting that, "even when he was a medical student, he was employed as a drug-advertising copywriter."

Throughout his career, Arthur Sackler took on overlapping responsibilities with seemingly obvious conflicts of interest — including the publishing of medical journals and running of advertising campaigns for drug companies, while retaining an ownership stake in the family's own drug-making firm.

In the 1950s, "using sustained personal contact with doctors, Arthur first marketed an antibiotic, Terramycin, for a then-unknown chemical company, Pfizer," Poltico reported. "In the 1960s, Arthur used these strategies to turn Valium into the industry’s first $1 billion drug."

“The Sackler empire is a completely integrated operation," explained a memo written in the early 1960s for an investigation by Estes Kefauver, the U.S. Senator from Tennessee best known for leading hearings that exposed organized crime nationally. The Sacklers' business could develop a drug, the memo said, then "have the drug clinically tested and secure favorable reports on the drug from the various hospitals with which they have connections, conceive the advertising approach and prepare the actual advertising copy with which to promote the drug, have the clinical articles as well as advertising copy published in their own medical journals, [and] prepare and plant articles in newspapers and magazines.”

Throughout the 1960s, various firms controlled by Arthur Sackler "created and distributed free 'articles' to newspapers and other publications that were really marketing plugs sold by his drug-company clients," Meier wrote in Pain Killer. "Purdue would later use this same strategy in an effort to boost OxyContin sales, distributing 'surveys' to spotlight the inadequate treatment of pain."

The Rise of OxyContin and the Opioid Crisis

In the 1980s, Purdue Pharma launched MSContin, an "extended-release" tablet containing morphine that was released slowly to the user. ("Contin" is supposed to give the idea it's continuous.) OxyContin was created also as a longer-lasting painkiller, only it incorporated the opiate oxycodone as the key ingredient.

In OxyContin's first five years on the market, Purdue Pharma hosted more than 40 all-expenses paid pain management conferences attended by over 5,000 doctors, pharmacists, and nurses, according to a 2009 article in the American Journal of Public Health. Purdue's marketing plan, which included the tracking of how many prescriptions were written by physicians all over the country in order to boost sales, was phenomenally successful.

"Sales grew from $48 million in 1996 to almost $1.1 billion in 2000," the journal article stated. "The high availability of OxyContin correlated with increased abuse, diversion, and addiction, and by 2004 OxyContin had become a leading drug of abuse in the United States."

Purdue developed a reputation for paying its sales representatives the highest bonuses in the pharmaceutical industry, according to Politico. Sales reps were allegedly instructed to push the idea that OxyContin was "virtually non-addicting" and should be prescribed for all kinds of chronic and long-term pain, including common conditions like arthritis.

“There is no question that the marketing of OxyContin was the most aggressive marketing of a narcotic drug ever undertaken by a pharmaceutical producer,” Painkiller author Meier said in the 2016 PBS Frontline documentary Chasing Heroin.

“At the time, we felt like we were doing a righteous thing,” Steven May, an OxyContin rep who joined Purdue Pharma in 1999, told the New Yorker. He then thought: “There’s millions of people in pain, and we have the solution.”

In fact, evidence indicates that OxyContin is highly addictive and dangerous. Nearly 80% of heroin users say their drug habit first started with prescription opioids such as OxyContin. Among other things, OxyContin "became abused by addicts who would crush the pills for a quick, intense high, sparking controversy and legal action against Purdue," Forbes reported.

The Sackler Family and OxyContin Lawsuits

Lawsuits targeting Purdue Pharma and its misleading marketing of OxyContin date back more than a decade. In 2007, Purdue and three executives pleaded guilty in federal court to "misbranding" the drug by falsely saying that OxyContin was less likely to result in abuse and addiction than other painkillers like Vicodin. Purdue Pharma agreed to pay $600 million in fines, and three company executives also agreed to $34.5 million in fines themselves.

Many more lawsuits have followed, launched by cities, counties, states, and families affected by OxyContin and the opioid crisis. On March 26, Purdue Pharma reached a settlement in a suit filed by the Oklahoma attorney general, agreeing to pay $270 million and help establish research facilities for studying and treating addiction. As part of the settlement, the Sackler family agreed to pledge $75 million over five years to the National Center for Addiction Studies and Treatment at Oklahoma State University.

Lawsuits filed against Purdue Pharma and the Sacklers are still alive in Massachusetts and New York, among other places. The Massachusetts suit disclosed documents showing that the Sacklers periodically voted at board meetings to pay themselves hundreds of millions of dollars from company profits — $450 million in 2008, and another $335 million the next year.

Prosecutors say they have evidence showing that even after the $600 million federal settlement in 2007, Sackler family members actively pushed Purdue executives and sales staff to sell more opioids, perhaps by launching a generic version of OxyContin. Sackler board members also supported a Purdue Pharma plan created in 2014 called Project Tango, in which the company sought to profit by selling treatments for addiction to drugs such as OxyContin, the New York Times reported.

In yet another twist, Purdue Pharma has reportedly been exploring the possibility of filing for bankruptcy, which could halt some of the lawsuits and allow the company to negotiate legal claims and settlements.

The Sackler Family's Billionaire Lifestyle

In addition to donating millions to colleges and museums, the Sacklers have used their riches to enjoy lavish lifestyles, globetrotting and buying homes in ritzy destinations like Bel Air, California, and Gstaad, Switzerland.

When Mortimer Sackler, one of the three original founding brothers, died in 2010 at the age of 93, he owned homes in London, Gstaad, and Antibes in the South of France. Mortimer Sackler lived primarily in England, had an English wife, and was awarded knighthood in 1999 for his philanthropic gifts to institutions such as Westminster Abbey, Oxford University, and the Royal Opera House. A special breed of rose in England is called the Mortimer Sackler, because his wife Theresa bought the naming rights to the flower at a charity auction in 2002.

Raymond Sackler, the last surviving of the brothers who founded Purdue Pharma, died in 2017 at the age of 97. He was also granted honorary British knighthood, receiving the award from Queen Elizabeth II in 1995 for his philanthropy and achievements in science. Raymond Sackler lived near the Purdue Pharma headquarters in Greenwich, Connecticut, one of the most exclusive and expensive towns in America.

Purdue Pharma profits and the Sacklers' family fortune have been passed down to the younger generations. Several Sackler family members have owned homes in Greenwich, including Raymond Sackler's son Richard, a trained physician and former president of Purdue Pharma who is often credited (or blamed) for Purdue's ultra-aggressive approach to selling OxyContin. Richard Sackler called Greenwhich home before getting divorced in 2013 and moving to a mansion in Austin, Texas.

Sophie Sackler, the daughter of Mortimer and Theresa, is married to the former English cricket star Jamie Dalrymple, and they live in a nine-bedroom $40 million home in the Chelsea neighborhood of London. Sophie's brother Mortimer and his wife Jacqueline Sackler own a townhouse in Manhattan, as well as a retreat in the Hamptons so impressive it was featured in Vogue in 2013.

Raymond Sackler's grandson, David Sackler, bought a 10,000-square-foot Bel Air estate in the hills outside Los Angeles last year. The sales price was $22.5 million, and he reportedly made a cash purchase.

“I don’t know how many rooms in different parts of the world I’ve given talks in that were named after the Sacklers,” Allen Frances, the former chair of psychiatry at Duke University School of Medicine, said to the New Yorker in 2017. “But, when it comes down to it, they’ve earned this fortune at the expense of millions of people who are addicted. It’s shocking how they have gotten away with it.”

Depending on lawsuits filed against the Sacklers and Purdue Pharma proceed, however, they may not be able to get away with it much longer.