For the First Time Ever, Index Funds Have More Money Than Active Funds

Money is not a client of any investment adviser featured on this page. The information provided on this page is for educational purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. Money does not offer advisory services.

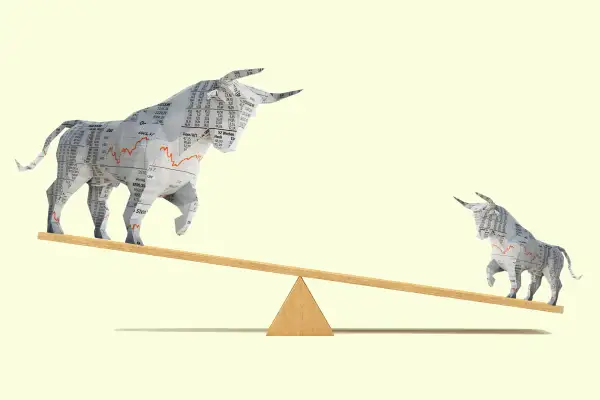

Indexing just became the undisputed heavyweight champion of the stock market, and small investors should be cheering the victory.

The amount of money in passive U.S. stock mutual funds exceeded that in actively-managed holdings for the first time in August, completing a transformation that began with the invention of the index fund more than 40 years ago, according to a recent report by fund-research firm Morningstar.

"This is a win for ordinary investors who are keeping more of their hard-earned savings for themselves," said Ben Johnson, director of passive strategies research at Morningstar, in an e-mail. "Average investors can now build a globally-diversified portfolio at a fraction of the cost and with a far lower minimum investment than they could 10 years ago."

There were $4.271 trillion assets under management in passive U.S. equity funds – ETFs and index funds -- overtaking the $4.246 trillion in actively managed funds – mostly mutual funds – as of Aug. 31, Morningstar reported.

Once a decided underdog, passive funds have steadily won fans over the past decade. During the past 10 years, investors yanked about $1.4 trillion from active U.S. stock funds, with most of the money -- $1.3 trillion – going to passive funds, according to Morningstar.

Before the launch of the Vanguard 500 index fund in 1976, there was almost no way around the tony brokerage and mutual-fund firms that acted as the gatekeepers of the stock market. Investors were accustomed to paying investment fees measured in full percentage points as opposed to the hundredths of percentage points common today. The refrain was: “where are the customers’ yachts?” The first ETF, an index fund that could be bought and sold during market hours like a stock, appeared in 1990, just as online trading was becoming possible through discount brokerages, leveling the gates and providing cheap, transparent and direct access to stocks.

Bear markets in 2000 and 2009 rattled investors’ faith in the ability of active managers to fulfill market-beating promises.

As investors returned to the stock market during the bull cycle that began in 2009, many did so by buying ETFs. ETF investment fees shrank to negligible levels, leading to the so-called race to zero that drew in traditional active managers like Fidelity.

“In some sense that’s kind of the history of financial markets,” said Jim Paulsen, chief investment strategist at money manager the Leuthold Group. The passive-investing boom “is an extension of what’s been going on throughout the Postwar era in the financial business in general,” as first commissions and then fund fees were “compressed” by competition, said Paulsen.

Index funds' massive size worries some. Investor Michael Burry, made famous by The Big Short, recently argued that the rapid growth of passive investments is not a natural evolution of markets but merely the latest too-good-to-be-true speculative bubble.

In an interview with Bloomberg News earlier this month, Burry compared investors' wholehearted embrace of index funds to the blind rush of money into collateralized-debt obligations ahead of the financial crisis. He argued that an indiscriminate influx of money had poured into large-cap stocks simply because of their index membership, a dynamic that could create trouble if investors suddenly get jittery and rush for the exits.

Others dismissed the concerns. “ETFs do not spell C-D-O,” said Matthew Bartolini, head of SPDR Americas ETF research at State Street Global Advisors. During the market down turn in the fourth quarter of 2018, equity ETFs saw in-flows, not out-flows Bartolini said. That would belie the argument that ETFs exacerbate such panics, he added.