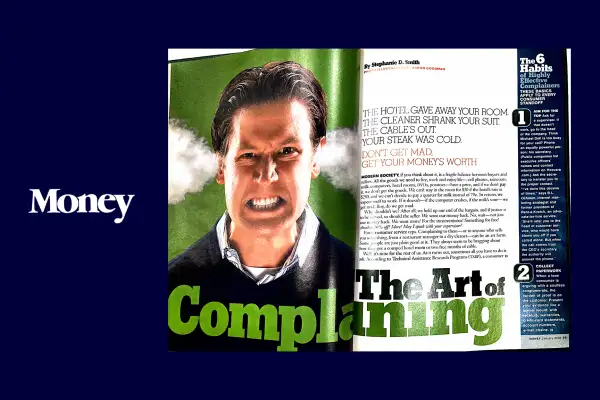

Money Classic: Perfecting the Art of Complaining (2005)

Money is turning 50! To celebrate, we’ve combed through decades of our print magazines to uncover hidden gems, fascinating stories and vintage personal finance tips that have (surprisingly) withstood the test of time. Throughout 2022, we’ll be sharing our favorite finds in Money Classic, a special limited-edition newsletter that goes out twice a month.

This excerpt, featured in the eighth issue of Money Classic, comes from a story in our January 2005 edition.

Editor's note: This story includes language that isn't inclusive. Preferred language is always evolving, and Money is committed to writing stories that do not discriminate on the basis of race, color, sex (including gender identity and sexual orientation), religion, age or disability.

Modern society, if you think about it, is a fragile balance between buyers and sellers. All the goods we need to live, work and enjoy life — cell phones, raincoats, milk, computers, hotel rooms, DVDs, potatoes —have a price, and if we don't pay it, we don't get the goods. We can't stay in the room for $50 if the hotel's rate is $250, and we can't decide to pay a quarter for milk instead of 79¢. In return, we expect stuff to work. If it doesn't — if the computer crashes, if the milk's sour — we get mad. Boy, do we get mad.

Why shouldn't we? After all, we held up our end of the bargain, and if justice is to be served, so should the seller. We want our money back. No, wait — not just our money back. We want more! For the inconvenience! Something for free!

Another 10% off! More! May I speak with your supervisor?

Enter customer service reps. Complaining to them — or to anyone who sells you something, from a restaurant manager to a dry cleaner — can be an art form. Some people are just plain good at it. They always seem to be bragging about how they got a comped hotel room or two free months of cable.

Well, it's time for the rest of us. As it turns out, sometimes all you have to do is ask. According to Technical Assistance Research Programs (TARP), a consumer service research firm, for every person who files a complaint about a consumer problem, seven do not — but each of those seven tells nine friends about the problem rather than someone who could actually solve it. And those friends tell their friends. Meanwhile, it costs companies six times more to obtain a new customer than to keep an old one. It's usually in their interest to right wrongs.

But not every caller to the toll-free number gets the same restitution. To help you get more for your minutes on hold, Money asked veteran customer service representatives, retail and service managers, consumer advocates and self-described masters of complaining for their best advice on lodging a fruitful grievance. We came up with six basic rules of complaining — or kvetching, as they say in Yiddish — and then applied them to a dozen common scenarios. We can't guarantee that you'll get a free lunch every time, but you never know. So call, follow these rules, and demand that the offending company hold up its end of the bargain. Operators are standing by.

1. Aim for the top

Ask for a supervisor. If that doesn't work, go to the head of the company. Think Michael Dell is too busy for your call? Phone an equally powerful person: his secretary. (Public companies list executive officers' names and contact information on Hoovers.com.) Ask the secretary to transfer you to the proper contact.

"I've done this dozens of times," says B.L. Ochman, Internet marketing strategist and former president of Rent-a-Kvetch, an advocate-for-hire service. "She'll refer you to the head of customer service, who would have blown you off if you called alone. But when the call comes from the CEO's secretary, the authority will answer the phone."

2. Collect paperwork

When a lone customer is arguing with a soulless conglomerate, the burden of proof is on the customer. Present your evidence like a lawyer would: with receipts, warranties, credit-card statements, account numbers, e-mail chains.

3. Start friendly

The service reps we interviewed roundly affirmed that too many complainers are irascible or uncivil. While the anger might be warranted, the attitude works against you.

"The customer service rep is not the culprit," says Herb Denenberg, a longtime consumer advocate and former professor at the Wharton School of Business. "You may have been ripped off, but the representative is there as a jury to hear and decide your case. A lawyer wouldn't get surly with a jury. A lawyer wants the jury to like him."

John Goodman, president of consumer researcher TARP, tells a story about one of his staff members observing an airline ticket counter during a flight delay. A man started shouting expletives at the agent, who stayed calm. When asked how she kept her cool, the agent replied, "Each time he cursed at me, his bag went farther from his destination."

4. Take names

Especially when complaining over the phone, asking for a name early in the conversation encourages a rep to stand at attention. "It makes them accountable for what they say, says Ochman. To avoid setting the wrong tone, though, say this: "I want to let your supervisor know how helpful you're being. What's your name?"

5. Know your regulators

The Federal Trade Commission, the Federal Aviation Administration and your local Board of Public Health — we all know those watchdogs exist, but we forget they exist for our benefit. Companies want nothing to do with them, so drop a name.

"If you mention the right commission," says Goodman, "the company will think, 'It costs money to report on the complaint. It'll be cheaper to get this taken care of right away.'"

Try saying, "I know the FAA has a policy about that, and I'm wondering if your solution complies with it."

6. Don't lie

Not that you would. But anyone in a huffing-and-puffing moment might feel an urge to say he's called four times already when in fact it's only been once. See, they have this thing today called technology, which can track every payment, every phone call, every consumer footstep. So be truthful, but don't be afraid to use a little melodrama. When, for example, a multibillion-dollar company tells you they can't waive the $29 fee listed in tiny print on your bill, say, "I saw something on TV about this, where companies were trying to sneak charges onto people's bills."

In terms of hoodwinking, it's less than what they're trying to pull. "I'm all for telling a few white lies if they help, but don't tell any darker shades," says Denenberg. "You don't want to impair your credibility."

Subscribe to Money Classic.