Where George Clooney's ‘Money Monster’ Hits (and Misses) the Mark

From Wolf of Wall Street to The Big Short, wealthy Wall Street types are becoming Hollywood’s favorite stock villains. It’s not exactly a huge secret why -- considering that millions of Americans are still digging out from the financial crisis. Now a new ripped-from-the-headlines thriller Money Monster, directed by Jodie Foster, is taking another shot -- and throwing some jabs at the media too.

With stars like George Clooney and Julia Roberts, the film is sure to generate buzz. But it’s not just a potboiler -- it aims to score points about greed, social class, and the perils of the global economy. Given that, does it succeed? The answer is yes...and no. As it happens, Money Monster starts off with biting, nearly spot-on depictions of our glib, 24-hour news media and the chaotic nature of our fast-paced electronic stock market. But as the drama builds the movie ends up facing a choice between what it really wants to be: entertainment or social criticism. This being Hollywood, entertainment wins out. But there's still plenty to parse. Here is your guide to what hits the target and what misses.

Jim Cramer...You Can't Make This Stuff Up

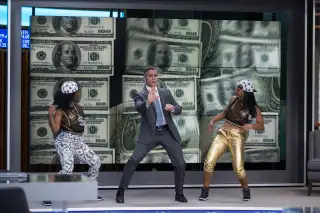

The film begins with fast-talking television host Lee Gates, played by Clooney prepping for his stock-picking show Money Monster. If you’re familiar with cable business television, you'll quickly recognize an only slightly exaggerated take on the frenetic, long-time host of CNBC’s Mad Money, Jim Cramer. While the real Cramer doesn’t actually use back-up dancers (at least not that I’ve seen), the sound effects and clubhouse are Cramer all the way.

Of course, the real Cramer doesn't look like George Clooney. (He declined to comment for this article, although affably suggested Louis CK was a better likeness.) But Cramer isn’t just a talking head: He’s worked at Goldman Sachs, run a hedge fund, and founded financial news site TheStreet.com.

Cramer's real-life admixture of investing and showmanship is controversial. Like Gates, stock picks are his signature. Observers have questioned his prowess, tracking his picks with sometimes disappointing results. But to be fair the real-life Cramer offers a disclaimer, admitting in his blunt style: “tips are for waiters.”

Televised Violence Is All Too Real

The movie kicks into gear when Kyle Budwell (Jack O’Connell), a fan who lost his savings on a bum tip, hijacks the show, holding Gates hostage live on air until he makes amends.

It's crazy but not unprecedented: Just last year a man who went by the name Bryce Williams murdered two former colleagues on air in Virginia, then used his Twitter account to attract widespread media attention before killing himself. There’s also precedent for disgruntled stock traders turning to violence. In 1999, a failed Atlanta day-trader named Mark O. Barton went on a rampage after loosing $100,000.

Of course, Money Monster's would-be terrorist is nothing like these real life killers. As Kyle pushes Gates toward introspection, the movie becomes an unlikely buddy picture. This is the least plausible aspect of the movie. But then, the financial shenanigans, which are harder to appraise, you probably knew that already.

(Warning: Mild spoilers ahead.)

High-Speed Trading Is A Dangerous Game

Kyle's losses aren't tied to just any stock but, IBIS Worldwide, a high-frequency trading firm, whose shares plunged after a trading glitch.

Why call out high-frequency trading? It's big business, representing for half or more of U.S. trading volume. It’s also controversial, beset by accusations traders get special treatment from exchanges. This case was recently outlined, Flash Boys, by star financial author Michael Lewis. But high-frequency trading has defenders too, who argue it makes trading cheaper for everyone.

One thing is clear: High-frequency isn't risk free. One Money Monster plot point -- the "glitch" that supposedly causes IBIS lose hundreds of millions of dollars in market value -- may seem like a bit of Hollywood stage craft.

In fact, the movie is on firm ground. In 2012, Knight Capital, a high frequency trading firm that at one point accounted for more than 10% of U.S. trading volume, lost $440 million in a single day after software problems prompted it to buy stocks at erroneously high prices. Knight’s shares fell 60%, and the company was eventually acquired by another firm.

Investigative Reporting Moves At a Snail's Pace

Before too long Gates is prompting his staff to investigate what’s really going on with IBIS. The implication is that, if more journalists did their jobs (like in Oscar-winning 'Spotlight') Wall Street wrongdoing might be found out and punished.

But is that realistic? Yes and no. In one of the movie's laugh lines, a young producer -- summoned from a romantic encounter in a utility closet -- rushes to a government building in Manhattan to secure a financial filing that helps the mystery around IBIS. Anyone who remembers Enron knows, there's a grain of truth to this. But just a grain. The producer enters the building in one scene then emerges the next with a single sheet of paper, as if he'd grabbed a clue in a scavenger hunt. By contrast, the months that go by in the excellent ‘Spotlight,” reveal just how long and frustrating such paper chases can be.

News organizations should do more investigative reporting. But in an age of cat videos and exploding watermelons, they skimp for the same reason Money Monster does: Audiences lack patience.

(Okay, now for some big-time spoilers.)

Real CEOs Are Smaller-Than-Life Villians

With Lee’s team on the case, we learn IBIS's losses weren't the result of a glitch after all. It’s a plot -- involving secret payoffs and striking South African miners. Behind it all is the CEO, Walt Camby, played by Dominic West.

Details of the scheme aside, it’s here where Money Monster lands farthest from the mark. It’s not that the conspiracy is outlandish. (Although it is. It’s all in good fun.) The problem is that, in the name of convenient storytelling, the movie pins Budwell's (and society's) problems on a brilliant but nefarious CEO. That's not just unlikely. It undercuts the movie's moral message, making it seem like economic unfairness -- that in real life is the result of self-dealing and the class chauvinism of our intellectual elite -- could be solved if just managed to catch and punish a few bad apples.

In the real world, notorious CEOs, when we see them up close, never appear as cunning like Walt Camby. Think of former Citigroup CEO Charles Prince telling investors, on the eve of the financial crisis that, “As long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance.” Or Bear Stearns CEO James Cayne playing in bridge tournament as his company collapsed. Or Lehman Brothers CEO Richard Fuld, still explaining to anyone who will listen that the company's demise wasn't really his fault.

That isn't to let these leaders off the hook but to suggest that they are merely regular people -- arrogant, glib, seemingly unable to understand how their actions affect those around them. In other words, not unlike the portrait the movie paints of Lee Gates -- before he's jolted out of his comfortable world. In real life, that's villain enough.