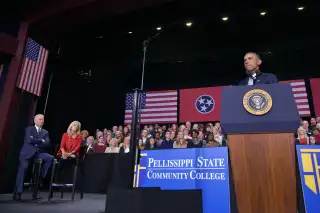

The Problem With Obama's "Free Community College" Proposal

President Obama’s ambitious proposal to make community college tuition free would certainly make enrolling in college more affordable. It may also induce students to stay there longer.

However, reducing costs for students on its own is unlikely to significantly increase the number of students who finish degrees. Consider: Of all of the students who enrolled in public community college for the first time in the fall of 2003, only one-quarter earned any kind of certificate or associate’s degree within six years. Another 12% earned a bachelor’s degree within that six-year period.

If we want to significantly improve educational outcomes, we need to both make college more affordable so more students can enroll, and make the reforms needed to ensure community college students can succeed in their courses, complete their programs, and graduate within a reasonable amount of time.

President Obama’s plan would certainly make community college more affordable. Even for the 40% of community college students whose tuition is already covered by federal and state aid, other expenses (food, transportation, books, etc.) often present insurmountable hurdles. If grants are awarded to eligible students on top of free tuition, as President Obama proposes, then many of these affordability issues would be addressed.

But the Tennessee and Chicago free tuition policies that inspired President Obama also address the broader barriers to success. The affordability improvements in those communities are one part of larger reforms designed to dramatically boost the success of community college students by providing close monitoring of student progress, careful alignment of courses to transfer and job requirements, clearer and more coherent programs of study, and help for students to make better choices about what to study.

Such reforms, many features of which have also been enacted in the City University of New York’s Accelerated Studies in Associate Programs (ASAP), have doubled the graduation rate for participants. But at a cost: ASAP costs 60% more per student than the standard CUNY program.

Laudably, President Obama’s proposal does try to address quality. It includes requirements that community colleges “adopt promising and evidence-based institutional reforms to improve student outcomes.” But his plan does not provide colleges with additional resources to help them in these efforts.

In fact, it is possible that his plan could reduce the money community colleges are able to spend on improving outcomes.

The White House estimates that the free tuition program would cost $6 billion a year. But that money would simply replace the tuition students were already paying, not increase colleges' revenue. States would be required to pay for one-quarter of this tuition subsidy. Some may raise that money by decreasing the direct subsidies they give colleges now, which currently cover approximately two-thirds of the cost of educating each student.

Despite these obstacles, the president’s proposal opens the door to a broader discussion of a comprehensive strategy for community colleges that emphasizes both affordability and performance.

Community colleges are the launchpad for opportunity for all Americans, enrolling almost half of the nation’s undergraduates. They are especially crucial for those who have, traditionally, been excluded from other kinds of higher education.

For these millions of students seeking brighter futures at community colleges, we need bold and transformative change and renewed public investment to ensure they have college options that are both affordable and of high quality.

Thomas Bailey is director of the Community College Research Center at Teachers College, Columbia University and co-author of the forthcoming Redesigning America’s Community Colleges (Harvard University Press, 2015).

Judith Scott-Clayton is a senior research associate at the Community College Research Center at Teachers College, Columbia University.