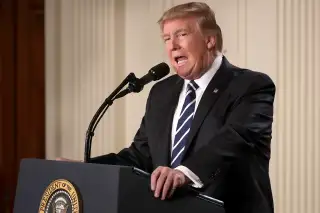

Donald Trump Promised to Lower Your Taxes. Will He?

Donald Trump was swept into office on a pledge to cut taxes more than any President has in nearly four decades. And if the first few weeks of his presidency are any indication, this POTUS aims to make good on his pledges—even the controversial ones.

He also starts with the strongest hand of any newly seated GOP President since 1929, with solid control of the House and Senate. “Congress is in the mood to adopt a comprehensive overhaul, not just tinkering,” says Alan Viard, a scholar at the American Enterprise Institute. But while Trump and congressional Republicans agree on broad goals like lower rates, their approaches differ—on issues ranging from corporate tax rates to the treatment of key deductions.

Even the pundits are wary of guessing how things will unfold. But here's a roundup of what the experts believe are the reforms that Washington is most likely to tackle, those it still needs to hash out, and a few that could come as big curveballs.

LIKELY AND IMMINENT

As President Trump and congressional Republicans start negotiating tax cuts, these policy moves are most likely to be front and center.

Lowering the Income Tax Brackets

Nothing would drive home Trump’s populist theme more than cutting personal income tax rates. “It’s a very visible way to cut taxes,” says Howard Gleckman, senior fellow at the Tax Policy Center. Plus, “since Ronald Reagan, Republicans have been arguing that one of the most, if not the most, important ways to boost growth is to lower tax rates.”

Both Trump and GOP leaders in the House of Representatives want to consolidate today’s seven brackets to three—12%, 25%, and 33%. Under both plans, top earners are likely to see rates fall from 39.6% to 33%, saving them $66 for every $1,000 taxed at the top rate.

But one big difference is where the top marginal rate kicks in. Under Trump’s plan, the top rate starts at $127,500 for single filers. So unmarried workers earning $127,500 to $200,500, currently in the 28% bracket, would actually face a higher top rate. Under the House plan, everyone in today’s 28% bracket would pay a top rate of 25%. The top 33% rate would kick in at $202,150 for single filers.

Raising the Standard Deduction

There’s another point of general agreement: The White House and congressional Republicans want to increase the standard deduction. If Trump has his way, it would climb to $30,000 for joint filers, up from $12,600 last year. The House plan would hike it to $24,000. That could simplify filing for millions of Americans. As many as 38 million of the 45 million tax filers who itemize could simply take the standard deduction instead under the House’s comprehensive reforms.

But both plans get rid of or curtail personal exemptions—the $4,050 you can deduct for each member of your family, available to couples earning less than $311,300 last year (and singles at less than $259,400). Trump’s plan would also eliminate the head of household filing status, used by about 23 million single parents. Together those provisions could mean higher taxes for some families.

An analysis by NYU professor Lily Batchelder found that a single parent of two kids earning $75,000, without childcare costs, would pay an added $2,440 under Trump’s plan.

Cutting Capital Gains Taxes

Congress has already taken steps to begin repealing Obamacare, and that means it’s likely that capital gains taxes for high earners are headed lower. The Affordable Care Act is funded in part by a 3.8% surtax on investment income, which pushed the top rate on long-term capital gains last year to 23.8% for couples making $466,950 or more.

But congressional Republicans may not settle for going back to 20%. House Speaker Paul Ryan wants to make half of capital gains tax-free and tax the rest like income. Based on the proposed 33% top bracket, the top capital gains rate could fall to 16.5%.

Eliminating State Tax Deductions

Even assuming tax cuts will lift growth, experts on both sides agree they won’t pay for themselves. One tax break with a target on its back: the ability to deduct state and local taxes. Not only does this cost the Treasury roughly $50 billion a year, but Republicans worry that this deduction subsidizes profligate spending by state legislatures. Those who would be hit hardest by this move also happen to live in high-tax blue states like California (13.3% top income tax rate) and New York (8.82%).

POPULAR BUT CHALLENGING

These tax changes are popular among GOP leaders, but key details still need to be hashed out for a greater likelihood of passage.

Eliminating Estate Taxes and the AMT

“Estate tax repeal has been on the Republican wish list for decades,” says Gleckman. “There is a good chance it gets repealed.” The right-leaning Tax Foundation says the move could boost growth by nearly 1% over the next decade, as inherited wealth is reinvested. That’s about the same impact as lowering and rejiggering income brackets, but costs about one-sixth as much in lost revenue. But focusing on this issue will let Democrats raise issues of economic inequality. The tax, which applies to estates with assets of $5.49 million this year, affects about 5,000 estates.

There is more bipartisan support for repealing the alternative minimum tax—a separate gauge of tax liability originally designed to keep the wealthy from avoiding paying their fair share but that now affects a broader swath of Americans. One potential obstacle to repeal: The AMT is forecast to bring in more than $350 billion in revenues from 2016 to 2025.

Cutting Corporate Taxes

An overhaul of corporate taxes won’t affect you directly, but it could impact your stocks. At 35%, the top U.S. rate is among the highest in the world. The Obama administration proposed a cut in 2016, only to watch legislators bicker over key details, like how to treat the $2.4 trillion in overseas profits that U.S. firms are keeping abroad to avoid taxes.

Trump wants a 15% rate, while letting firms repatriate foreign profits held in cash at 10%. House Republicans seek a 20% top rate, with “border adjustability.” Companies would get to keep profits on exports tax-free. But when they sell goods in the U.S., they wouldn’t be able to deduct the cost of imports from profits. Trump has already disparaged the plan.

WILD-CARD TAX CHANGES

Many of the following are long shots but could have a big impact if enacted.

Addressing Childcare Issues

During the campaign, Trump proposed allowing parents to deduct childcare costs—up to the average cost of care in their state—from their income taxes. For low-income parents, he offered a $1,200 rebate.

Support from Democrats makes it look like no-brainer, right? Not so fast. Trump’s plan could cost $150 billion to $550 billion, according to the American Action Forum. And an expensive new deduction goes against GOP desires to eliminate tax perks to streamline the tax code and lower rates.

Creating a Special Business Tax Rate

Trump and congressional Republicans have proposed taxing business owners such as doctors, law partners, and freelancers at lower rates than wage earners. The idea is to help “job creators” by taxing them like large public firms. Congressional Republicans want businesses to pay a top rate of 25%, while Trump seeks an even more generous 15%.

But while there are 28 million small businesses in the U.S., only 5.7 million employ anyone other than the owner. And of these, only about 200,000 are the kind of “high growth” companies that tend to add lots of workers, a recent Harvard study found.

Eliminating 'Third-Rail' Deductions

Republicans could pay for a much bigger rate cut if they limit or eliminate popular and politically charged deductions like those for mortgage interest ($75 billion a year in lost revenue) and charitable giving ($47 billion). Both rank among Uncle Sam’s top 10 tax expenditures. Separately, Trump has proposed capping the value of deductions across the board for the wealthy (at $200,000 for married filers; $100,000 for singles).

Getting rid of these deductions could have a big impact. A Federal Reserve study found that eliminating the mortgage deduction could knock 11% off home values, at least in the short term, as demand would be expected to fall. But reform on this scale remains a long shot, says the Tax Policy Center’s Gleckman.