How a Bowl of Cashews Changed the Way You Save for Retirement

Money is not a client of any investment adviser featured on this page. The information provided on this page is for educational purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. Money does not offer advisory services.

As young academic in the 1970s, the economist Richard Thaler began compiling what he calls "the List," a collection of the everyday ways in which real people fail to act as economic theory predicts. One item on the List: the puzzling reaction of his friends at a party when Thaler took away a bowl of cashews. The List became the seed of his pioneering work in the new field of behavioral economics, a field that has, among other things, transformed how 401(k) plans are designed. (If you were automatically signed up for your company's retirement plan, you can thank behavioral research.)

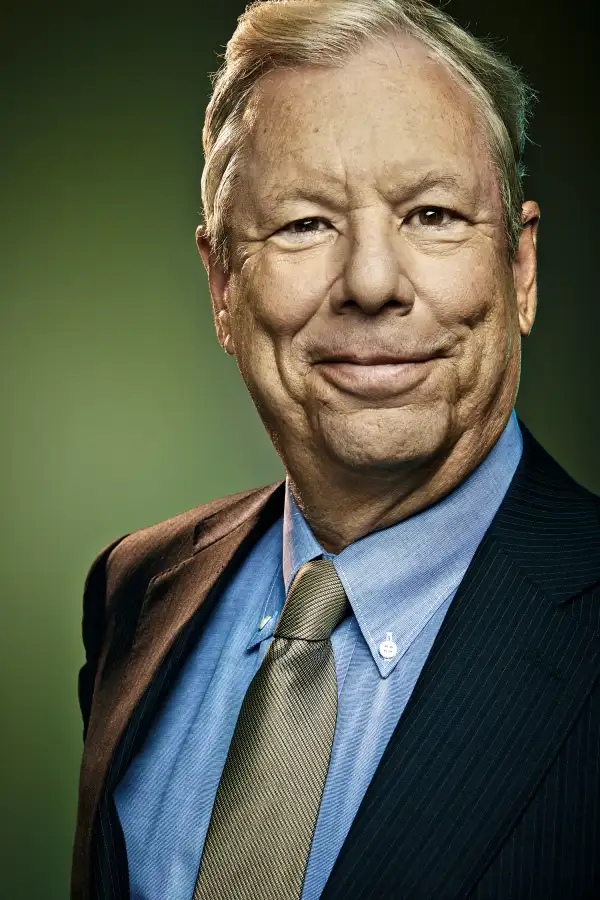

Thaler, 69, is a professor at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. (He tweets at @R_Thaler.) His new book Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics was published on May 11. Money editor-at-large Penelope Wang interviewed Thaler for the June issue of the magazine. The interview, which was edited, starts with a discussion of what happened with those cashews.

How can I make smarter money choices?

It helps to have what I call nudges. The lesson of my field, behavioral economics, is that we need to understand the ways in which we differ from the rational human assumed in standard economic theory. I call this idealized person the “Econ.”

My classic example of the difference between Econs and actual humans is something that happened years ago. I was having a dinner party for fellow economics grad students. Before dinner I served some cashew nuts along with cocktails, and everyone kept eating them. Soon their appetites were in danger, not to mention their waistlines. I grabbed the bowl and hid it in the kitchen. People were (a) happy, and (b) they realized their reaction conflicted with traditional economic theory. Econs are better off with more choices. We humans actually need help controlling our impulses—nudges.

How would “hiding the cashews” work with money?

Here’s a model of saving for retirement that’s guaranteed to fail: Decide at the end of every month how much you want to save. You’ll have spent a lot of the money by then. Instead, the way to really save is to put the money away in a 401(k) even before you get it, via a payroll deduction. And behavioral economics says a little nudge can help you to do that even better.

In 1994 I wrote an article advising auto-enrollment in 401(k) plans—putting people in the plan by default, while giving them an opportunity to opt out, so you still have a choice. Saving would happen without having to make decisions to do it every week or month. The 2006 Pension Protection Act even encouraged employers to use auto-enrollment, and now more than half of large plans do so. But many people still aren’t saving enough.

In fact, you say many plans are nudging people to save too little.

Most companies using auto-enrollment set the default contribution rate too low. It’s stuck at 3% of salary, which was never intended by the law. Can you get people to save more than the default? Part of the answer is to combine auto-enrollment with auto-escalation. Research I did with Shlomo Benartzi of UCLA showed that even if people think they can save only a little right now, they’re willing to accept future increases in contributions, such as when they get raises. A state-of-the-art 401(k) should start out with auto-enrollment at 6% and escalate to at least 10% or higher. The evidence shows raising the default to 6% won’t lead to a high opt-out rate.

Outside of a 401(k), how can knowing a bit about behavioral economics help me make better decisions? Psychology and economics professor George Loewenstein, at Carnegie Mellon, has a phrase: hot-cold empathy gap. It means you have two kinds of emotional states, hot and cold. So if I’m thinking about what to have for dinner in the morning, when I’m not hungry, I’ll say I’ll have fish and salad. I’m in a cold state. But by the time I go out for dinner, I’ll have a weakness maybe for a cocktail, I’ll see ribs and a big bowl of pasta—I’ll be in a hot state. I’ll order the ribs.

The point George makes is that people overestimate the self-control they’ll have in the hot state. So we need to make concessions to our frailties, such as choosing a restaurant with healthier choices or making a list before you go shopping, to help you buy only what you decided to buy in the cold state. If you’re not putting enough away for emergencies or retirement, making commitments in advance, such as signing up for payroll withholding, can help.

You helped discover something called the endowment effect. It seems like something that would affect investors. Tell us about it.

It was one of the first behaviors I studied, and it shows we demand more to give things up than we would pay to acquire them. We studied this by showing how students valued coffee mugs we handed out. People who got the mugs demanded twice as much to give them up as people who didn’t get the mugs would pay to get one. The endowment effect overlaps with other behavioral phenomena, such as loss aversion—seeking to avoid losses more than we seek gains—and a bias for the status quo. For these reasons, investors tend to hold on too long to stocks that have gone down, hoping they will rebound so they can sell without realizing a loss.

If people aren’t as rational as economists assume, can I take advantage of that as an investor?

That’s exactly what some professional investors are trying to do. Behavioral economics offers a plausible explanation for overreactions by the market. For example, a long period of bad performance can lead to stereotyping. There was a period when Apple was considered an inept company on the road to bankruptcy. That was an opportunity.

But it’s not easy to beat the market. Most professionals fail, and research shows individuals are abysmal market timers, buying high and selling low. I don’t think I can beat the market, but I think my firm can. [Thaler is a co-founder of a money management firm, Fuller & Thaler, but does not choose its investments.] I keep my money professionally managed or in index funds.

Maybe I could at least use behavioral insights to spot times when there’s an irrational bubble.

I don’t think most people can. For example, research shows people buy real estate based on naive extrapolations. “Real estate prices in Scottsdale will never go down.” I think we can make two conclusions: One, we’re really bad at this. Two, with investments like target-date funds, which diversify your assets and rebalance automatically, you can minimize the damage.

It seems so obvious that people make mistakes, but your book has gossipy fun recounting pitched academic battles over the idea. Why do economists resist it?

Some thought human errors were random and so would cancel each other out, which the work of [economics Nobel laureate] Daniel Kahneman and the late Amos Tversky found was not true. Most of the errors go in the same direction. Or they thought that if the stakes are high, people make the right decisions. The mortgage crisis showed that people still make mistakes when stakes are high.

Governments have been getting interested in behavioral economics. What are they doing with the research?

I’ve been working with a group within the United Kingdom’s government called the Behavioural Insights Team. One of the first experiments in the U.K. was to encourage more people to pay their taxes on time. We just changed the letter that was sent out to people who owed money, and added the true fact that 90% of people pay taxes on time. So the only difference was that we were telling people, “You are in the minority.” If you are an Econ, this should be irrelevant. But it brought in millions of pounds in tax revenue a lot faster.

There are all kinds of opportunities. Climate change is a behavioral problem—telling homeowners they use more power than their neighbors tends to reduce consumption. So is obesity. Health care costs are partly behavioral. It makes sense to ask behavioral scientists for their ideas, and then test them rigorously.

What about the worry that nudges can manipulate people? It’s just looking to see how we can help people without forcing them to do anything. We didn’t invent the idea of nudging people toward certain choices—it’s been around throughout human history. When the government employs these strategies, there are important ethical questions, and Cass Sunstein and I wrote about this in our book Nudge. We insist the government has to be transparent. Critics forget you cannot have a world without nudging. If people have to remember to sign up for a 401(k), the employer is effectively nudging them not to enroll. Either way, you have to decide what the default is. We advocate picking the one that makes people better off.