This Nobel Economist Spotted the Last Two Bubbles—Here's What He Says About the Bond Boom

Money is not a client of any investment adviser featured on this page. The information provided on this page is for educational purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. Money does not offer advisory services.

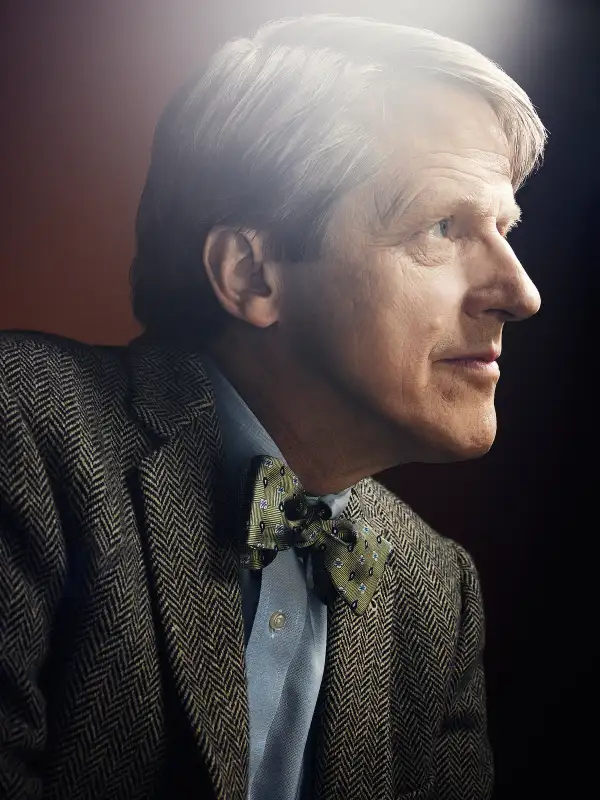

This month, Yale economist Robert Shiller, who shared the Nobel Prize in economics in 2013, is publishing the third edition of his classic book Irrational Exuberance. Some might take this as an ominous sign. The first version came out in 2000, and it made the case that stock valuations looked awfully high, and that people seemed too optimistic about tech stocks. You know what happened next.

The second edition, published in 2005, had a new chapter about the unusually high price of real estate. You know what happened that time, too.

Now Shiller has added a new chapter on another asset class that has become historically expensive: bonds. Should we be freaking out?

Bond prices rise when yields fall, and on Tuesday the benchmark Treasury yield slid below 2% for the first time since October. The long-term average for longer-term bond interest rates is 4.6%. Rates have been low ever since the 2008 financials crisis—and since at least 2009, some market observers have called the bond market a bubble.

Shiller, however, resists applying the B-word to bonds. “It doesn’t clearly fit my definition of ‘bubble,'” he says. “It doesn’t seem to be enthusiastic. It doesn’t seem to be built on expectations of rapid increases in bond prices.” (Shiller spoke with Money in December.) In the unlikely event you meet anyone at the proverbial cocktail party talking about bond funds, he’s probably complaining about the lousy yields, not talking about the killing he expects to make.

Still … Shiller does point to one similarity between today’s low yields and past bubbly episodes. Bubbles are a result of a psychological feedback loop: As asset prices go up, people come up with stories to explain why, which helps push prices higher, reinforcing the story, and so on. In the tech boom the story was of a new era of dotcom-fueled growth. The rationalizations about housing prices centered on cheap mortgages and financial “innovations.”

With bonds, too, says Shiller, “there are theories that have been amplified by the price performance.”

The low-rate story driving bond prices, however, is a gloomy one. Investors seek the relative safety of bonds—especially sure-to-pay-back Treasuries—when they feel pessimistic about the economy and comfortable that inflation will be low.

Professional bond managers today can tick off a host of factors weighing down rates and propping up fixed-income prices. There's inequality, which may be holding back spending. The risk of deflation (falling prices) in Europe and Asia. Bad demographic trends in developed economies. You can even add robots, says Shiller. “There’s a suggestion that computers are going to create a more unequal world, and that this is inhibiting people’s spending plans,” says Shiller. Instead consumers try to save more, bidding up the prices of assets.

The idea of an economy that never quite gets back to prosperity has been labeled “secular stagnation” and the “new normal”—the latter term popularized by Bill Gross, before he made his surprising turn away from Treasuries. (Gross recently left Pimco for Janus. Here is a 2010 interview with Money in which he discussed his “new normal” view. )

The “new normal” story is at least partly built into today’s bond prices. That means even if yields stay low, the strong return on bonds in recent years are unlikely to repeat. (As a rule of thumb, the current yield on a 10-year Treasury is also the total return you can expect over the next decade. So that suggests a slim 2% return.)

Shiller also points out that his research with Wharton economist Jeremy Siegel has shown that bond investors are pretty bad at anticipating inflation. Forget fever dreams of ′70s-style price hikes—a return to 3% inflation would render Treasuries a money loser in real terms. (Inflation is currently below 2%.) That doesn’t seem like such a high bar to clear. It’s what some economists think a healthy economy would look like.

That said, the slow-growth, mild-inflation scenario remains compelling. The last long period when rates were this low, before World War II, was followed by a long climb upward—but that coincided with postwar expansion, Cold War defense spending, and the baby boom. Maybe that was the anomaly. (If secular stagnation turns out to be real, here's what that might mean for investors.)

Low rates have probably been even more important, says Shiller, in driving up stock prices. With yields on bonds so meager, investors may have shifted money into stocks in hopes of getting a better return. In early versions of his new edition of Irrational Exuberance, Shiller described today’s bull market as the “post-subprime boom.”

“But I changed it at the last minute,” he says. Now Shiller calls this era “the new normal boom.”

This story is adapted from "How 2% Explains the World," in the 2015 Investor's Guide in the January-Feburary issue of Money.