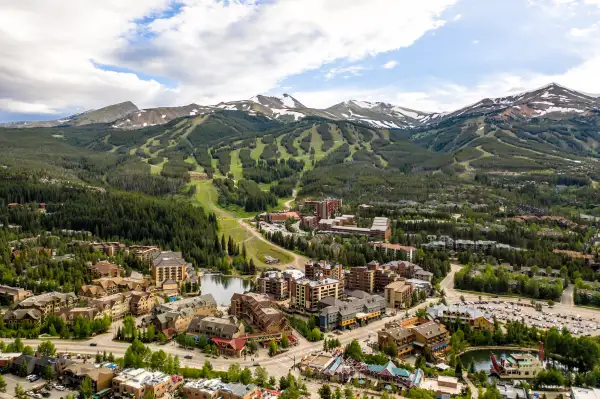

These Vacation Towns Are Limiting the Number of People Who Can Rent Their Houses as Airbnbs

Currently, 3,000 properties in the Town of Breckenridge, Colorado are licensed as short rentals, that's over 40% of the town’s total housing stock. These licenses cost up to $325 a year and allow property owners to legally rent out their homes for a few nights at a time through sites like Airbnb or VRBO. Now, the town is trying to get that number down to just 2,200.

That’s because in September the town council unanimously voted to place a cap on the number of non-exempt licenses in the popular skiing and hiking destination (short-term rentals with desk staff and security are exempt from the cap).

The hope in Breckenridge is that limiting the number of short term rentals will open up more housing for people who work in the town and make it more affordable to live there.

“People who work in restaurants, schools, or in first response are leaving because they can’t afford to live here,” says Mayor Eric Mamula, who also owns a restaurant in town. “Many of them have been kicked out of rental units that buyers are now using for short-term rentals.”

Small towns with big tourist draws have long struggled to balance the needs of visitors who provide revenue with the needs of locals who keep these places running. The problem has been exacerbated by the coronavirus, as well-heeled remote workers have taken up residence in their vacation homes or plowed earnings from home sales and a surging stock market into second properties.

According to vacation rental data site Airdna, the number of available listings in the United States dipped in 2020 but is rebounding and will reach 1.37 million in 2022 — up 16% from before the pandemic. Meanwhile, Airdna’s data shows 67% more listing nights sold in 2021 than 2019 in smaller cities and rural markets and 25% more demand in both destination and resort locations.

With all this in mind, several towns across the country have approved or proposed limits similar to Brekenridge’s this year.

The tiny town of Woodstock, NY, with a population of around 6,000 residents, voted to cap STR licenses to 285 and placed a nine-month moratorium on issuing new ones. Residents of Telluride, Colorado will vote in November on a proposal to restrict licenses to 400 annually, down from 822. In Annapolis, Maryland, a moratorium on the issuance of short-term rental licenses was defeated last summer.

Can these laws make a dent in the housing affordability crisis?

Advocates of these rules argue that limiting the number of short term rentals will open up more affordable housing to lower-income earners who work in these expensive towns. Critics see the laws as incomplete solutions to the affordability crisis and potentially counterproductive.

Keith Hampton, owner of Telluride-based SilverStar Rentals and Property Management, argues towns should focus on adding more affordable housing units, rather than capping STR licenses.

“When you cut STRs to the level proposed here, you’re drastically cutting into tax revenues, which impacts every business in town,” says Hampton. “There are other options, like increasing the STR license fees and using the funds for building affordable housing, while putting a freeze on licenses so that the pipeline can catch up.”

Tom Coale, a real estate attorney from Maryland, says that capping STR numbers is not the solution to affordable housing.

“The housing crisis is only going to be resolved by increasing the supply, subsidizing housing for those who need it, and providing stability for renters,” he says. “The presumption that STRs will instead become long-term rental properties isn’t likely the case. Capping STRs will not magically turn those units into affordable housing for a bartender or waitress.”

Adding, “If you create an environment of housing scarcity, people will find a way to profit from it, regardless of caps.”

A report from Moody’s Analytics on how to solve the affordable housing issue supports Coale’s thesis, and leaves out of its solutions capping STR licenses.

“The good news is that there is no single, prohibitive problem standing in the way of building more affordable housing, only a host of smaller ones,” says the report. “This of course leads to the bad news, which is that there is no one policy step that can be taken to deal effectively with the issue. Policymakers will need to take many.”

More from Money:

Some Homeowners Are Wishing They Never Agreed to Sell

Frustrated House Hunters Are Giving up on Buying Only to Face an Expensive Rental Market

What's Your Best Place? How to Decide Where to Live in a Pandemic-Changed World