Why Your Paycheck May Not Grow With the Economy

You may have heard that the U.S. economy is back. The nation's gross domestic product grew by 4.6% and 5% in the last two quarters—the strongest increase since 2003; Americans are more confident about the economy than at any time since the recession; and gasoline prices are as low as they've been in more than five years, amounting to a huge tax break for consumers and businesses.

No wonder employers felt strong enough to add 321,000 jobs to the economy in November, while the unemployment rate was at a post-recession low of 5.8%.

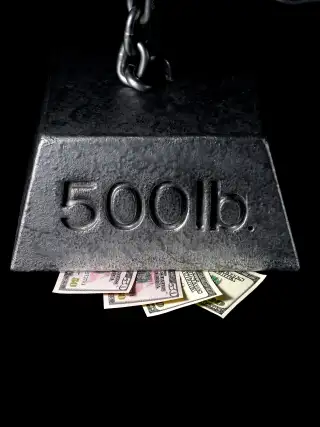

Still, many workers have not seen a pick-up in pay even as the employment climate has improved. In fact private sector wages declined by 5 cents (or by 0.2%) in December, despite the economy adding 252,000 jobs.

Total compensation, which includes benefits like medical insurance, rose 2.1% from the same period a year ago. That's actually a slight uptick from the post-recession norm, but well below pre-2008 levels.

Which is weird. As demand for workers improves, and the unemployment rate declines, you'd expect inflation to rise and wages to increase.

One reason why wages have grown so slowly is that for much of the recovery there's simply been a lack of demand for goods from consumers as many Americans worked to get out from the terrible effects of the housing crisis.

Since my spending is your income, more dollars saved and fewer spent mean less economic activity resulting in a weaker labor market. And since the Federal Reserve already dropped short-term interest rates to practically zero, and Washington lawmakers are reluctant or disinterested in further fiscal stimulus, marginal relief is coming from D.C.

Another explanation might have to do with the nature of compensation.

In a recent report, the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco highlighted the notion of "sticky" wages.

The argument goes: Since businesses were unable to reduce wages as much as they wanted when the economy got really bad five years ago (short of firing people), they are now not inclined to raise salaries as the economy lifts off.

If wages are rigid against a terrible economy, they're stagnant (at least for a while) when the tide turns. "Businesses hold back wage increases and wait for inflation and productivity growth to bring wages closer to their desired levels," says the report authors's Mary Daly and Bart Hobijn. "Since it takes some time to fully exhaust the pool of wage cuts, growth remains low even as the economy expands and the unemployment rate declines."

While there's a bit of rigidity to all wages, the authors found "industries with the most downwardly rigid wage structures before the recession have seen the slowest growth during the recovery." This means that businesses that were able to lower pay when revenues dried up have been more likely to increase wages as the good times returned.

So people in the wholesale trade business (truck drivers to sales reps) saw wages increase relative to pre-recession levels, while those in construction have to make due on less income.

What does this mean for workers?

"The rigidity of wages in a number of sectors has shaped the dynamics of unemployment and wage growth and is likely to do so until labor markets have fully returned to normal," per Daly and Hobijn. And with still elevated levels of the long-term unemployed, high numbers of workers in part-time positions that want full-time ones, and fewer people quitting their jobs than before the recession, we're still in not normal labor market territory.

Investors, especially older ones with larger holdings in fixed-income, should take note, too. Without higher inflation, and especially wage growth, the Federal Reserve is likely to delay raising rates.

While recent Fed meetings minutes have been interpreted as having a more hawkish tone, rates aren't likely to rise (or rise quickly) while workers still struggle to make up lost ground.

Updated to reflect on Jan. 9 jobs report.