20 Million Students Apply for Financial Aid Every Year. Here's Why Some of the Neediest Lose Out

For at least 5 million students each year, applying for financial aid doesn't stop when they submit the FAFSA.

If your application gets audited—a process technically known as "verification"—you can wind up in a holding pattern, unable to move forward until you are able to track down and submit additional documentation to prove what you reported on the form was accurate.

Those audits have become more common this year, according to data provided by the National Association for Student Financial Aid Administrators, with multiple colleges reporting double-digit increases in the share of applicants flagged for verification.

The problem: While about a third of all people who fill out the financial aid application have historically been selected to go through verification, more than 90% of those audits affect the poorest applicants—those who have finances that would qualify them for a Pell grant, federal aid for low-income students, according to the National College Access Network.

"This is disproportionately a burden that low-income students have to bear to prove that they're as low-income as they appear on the form," says Carrie Warick, director of policy and advocacy at NCAN, which has been working to put a spotlight on the issue.

One of the biggest concerns is that some of those poorer students will never make it through process at all.

At the 13 schools in the Colorado Community College System, for instance, 39% of the more than 90,000 students—most of them low-income, first-generation students—were flagged last year for verification.

More than half of those never completed the verification requirements, Nancy McCallin, president of the community college system, said at a Senate hearing Tuesday. That means no federal Pell grants, no low-interest federal student loans, and ultimately, no access to money that's supposed to help pay for college.

While each verification case is different, they can take weeks and sometimes months to resolve. They often require families to track down documents from the IRS—sometimes even documents confirming that they're not required to file a tax return—during the same time period that the IRS is swamped with tax filings.

What's more, colleges are in charge of confirming that the information on the FAFSA is accurate, and each college is allowed to set up its own process. That means a high school senior who has applied to multiple colleges and is flagged for verification has to comply with each college's process in order to clear up the issue and receive aid offers.

This can butt up against the spring deadline at many colleges to accept enrollment offers, giving students less time to compare various aid packages. Other students caught up in verification can lose out on first-come, first-serve grant money, says Warick, of NCAN.

One-third of about 600 aid administrators in a survey overseen by The Institute for College Access and Success last year said verification often spills over into the start of the semester, meaning award amounts are undetermined even as bills are due and class registration has passed.

The federal government doesn't release much information about what specifically triggers a verification flag, and there's also little national data on the outcomes of the process—neither how long it takes to resolve nor how many people end up giving up on the process altogether.

But McCallin's data from Colorado's community colleges suggests that the dropoff could be significant. And NCAN points to a discrepancy between applicants eligible for Pell grants who are selected for verification and those who aren't. Of those who were eligible and weren't flagged, 78% went on to receive the grant, compared with 56% of those who were selected for verification. NCAN calls that 22-point gap "verification melt"—applicants who leave the process because of the burden.

It's possible, of course, that the process is actually working and that, through verification, some of those students incomes' were determined to be too high to qualify for Pell. Yet findings in one recent paper from a team of researchers at Vanderbilt University suggest that doesn't explain the entire gap. In that research, looking at a single, four-year public university, 48% of applicants who had to complete verification saw no change to their expected family contribution—the federal calculation that determines Pell grant eligibility. And the TICAS survey found the just one in 10 aid administrators say the process often results in any significant changes to a students' aid package.

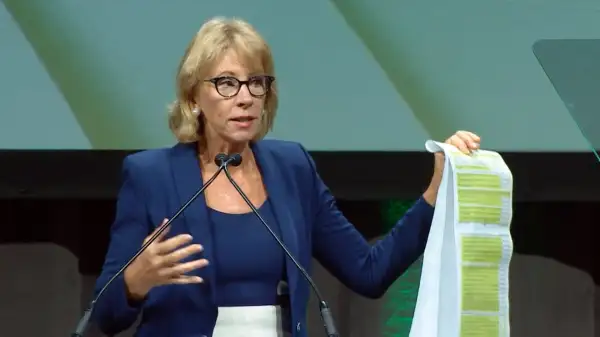

While verification is commonplace, it hasn't gotten the same level of attention as other issues related to improving the aid application process—such as reducing the number of questions on the FAFSA or standardizing aid letters, both of which are proposed in a recently introduced House bill on the topic. That began to change Tuesday during a Senate hearing on FAFSA simplification, where senators and expert witnesses spoke at length about the burden of verification.

Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) said he plans to introduce legislation to reduce the 108-question FAFSA to somewhere between 15 and 25 questions. That will likely include a combination of using information already reported to other federal agencies to pre-populate the form and eliminating unnecessary questions.

Simply reducing the number of questions won't be enough to solve the burden of verification, says Justin Draeger, president of the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators. Instead, it will require the aid application to rely as much as possible on information that's already been verified by the government—on tax returns, say, or applications for benefits such as supplemental security income or supplemental nutrition assistance program (SNAP).

And improving verification would benefit colleges as well.

McCallin, of the Colorado Community College System, said her colleges' financial aid administrators spend 25% of their time on verification. More than half of the aid administrators surveyed last year said the same. That's time, McCallin says, that could be devoted to counseling students instead of tracking down paperwork.

Any efforts to simplify the FAFSA require a balancing act: The goal is to reduce the obstacles to completing the form, while still collecting enough information to adequately target aid and appease the state agencies and colleges that use the FAFSA to award their own financial aid.

Solving verification will take a similar balancing act. The whole point of the process is to keep students who aren't actually eligible for limited need-based aid from receiving it. The question before lawmakers now is how can they continue to use verification as a check on aid awarding, while not making it so burdensome that it's actually a barrier.