This Common First Job Mistake Can Cost You $10,000 a Year for Life

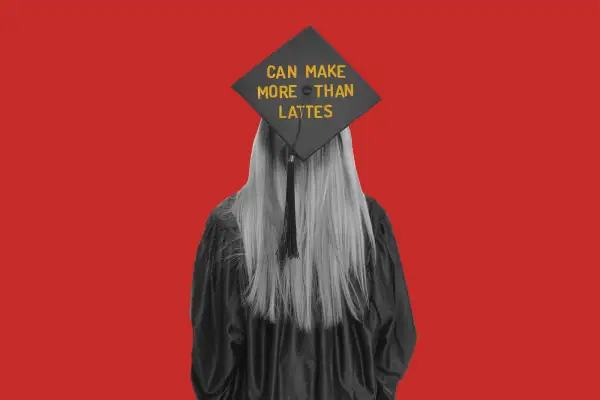

It’s not uncommon for young professionals to tread water for a bit after college, working at a coffee shop or in retail until something more permanent comes along.

But this temporary period of floating can reverberate throughout a person’s career — and cause some serious damage.

Researchers from the Strada Institute for the Future of Work and Burning Glass Technologies recently parsed through 4 million resumes to understand the career trajectories of college graduates. "Underemployment,” that middling state of workforce participation that lands grads in jobs they’re overqualified for, snares 43% of first-time job seekers, they found.

It gets worse: Two-thirds of those job seekers are still underemployed five years later, and 74% of those underemployed at the five year mark are still underemployed 10 years after graduating, according to the study.

“We tend to rationalize this experience as a rite of passage in moving towards a career,” says Michelle Weise, Strada’s chief innovation officer. “But underemployment is not at all a short term problem. Once you start out behind you stay behind.”

The trap of underemployment has serious financial implications: Underemployed graduates earn about $10,000 less per year than those in jobs that match their credentials, according to the study. Over time, that gap can widen even further; if you’re serving drinks at the local bar instead of chipping away at the career you went to school for, you’re not getting the raises, promotions, and networking opportunities that your peers are.

For women, who already make an average 20% less than their male colleagues, the threat of underemployment looms even larger. Nearly half of all female college graduates are underemployed in their first jobs, compared to 37% of male graduates, according to the study. This is significant, Weise says, because it strikes down the notion that motherhood, the so-called "mommy track," is responsible for the persisting gender pay gap. In reality, “women are set back from the beginning," she says.

STEM (Science, technology, engineering and math) majors, on the other hand, are less likely to be underemployed than the larger pool of graduates; only 30% of engineering and computer science graduates are underemployed.

That said, all hope is not lost for non-STEM majors. Once you find a job that matches your qualifications, you’re unlikely to fall back into a pattern of underemployment. So while a creative writing graduate might not be overjoyed with a job offer at a PR firm, she’s more likely to stay employed, move up the career ladder, and have autonomy over her future if she takes that job over a placeholder gig.

The key, Weise says, is to be deliberate. An entry-level job in office, administrative, or legal support can jumpstart a career, even if it's at a company that's only slightly related to what a young job seeker majored in. Flipping burgers? Not so much.

"Maybe instead of taking that job serving coffee, do something in a field you’re actually interested in progressing in ... an area with potential for upward mobility," she says. "Not something that’s a dead end.”