The Classroom Exercise That Turned Fourth-Graders Into Smarter Money Managers

Elementary school students are eager to engage in real-world economic decisions, and doing so significantly improves their money management skills and sets them on a clearer path to long-term financial security, new research shows.

Florida kids exposed to a 10-week program in the Palm Beach School District were 11% more likely to open a bank account and engage in other economic activity, according to findings from the University of Wisconsin Center for Financial Literacy. These kids were 9% more likely to have some kind of budget and 5% more likely to understand basic financial concepts and talk about money at home.

Read next: The Financial Literacy Test You Need to Pass

The findings add to a string of recent research showing that teaching kids about money gets results. An earlier study from the Center, for example, tied better credit scores to financial education in high school. The results also come as some experts have begun to dispute the value of financial education; they argue a better investment would be mobile technology that speeds vetted point-of-sale advice to consumers at crucial moments.

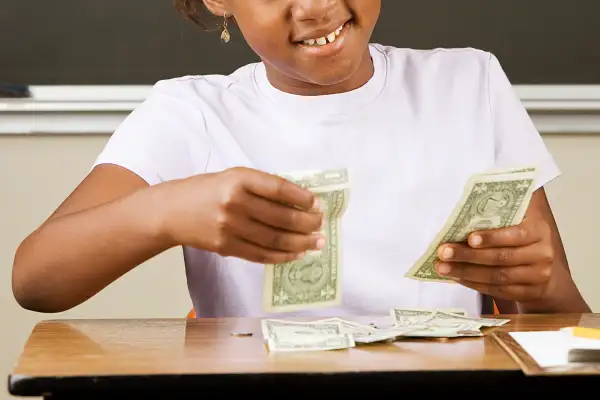

As educators, policymakers, and parents search for what works with kids, the new findings point to the effectiveness of experiential teaching as opposed to textbook lessons. In Palm Beach, a diverse group of nearly 2,000 fourth- and fifth-graders across 24 schools and 115 classrooms took part in a program called My Classroom Economy. The kids were given classroom jobs like taking attendance and passing out classroom materials. They got “paid” for their efforts and could earn bonuses for being on time and doing their homework. They could use their pay to buy things like a homework pass or more time with a computer. They could also be fined for, say, tardiness.

The kids basically lived in a simulated real-world micro economy and had to make choices that left them with more or less “money.” One of their “expenses” was their desk, which they could “rent” or “buy.” About a third did the math and decided buying made more sense in the long run.

Educators call this organic learning; the kids were not taught specific lessons. They learned by making decisions and feeling the results, which changed their behavior. “The effects were fairly impressive,” says J. Michael Collins, director of the Center. Given the abbreviated period of the study, Collins says, “We suspect the longer students are exposed to this kind of program we might see even larger effects.”

The program, made available to teachers free of charge through Vanguard, is in schools in every state. The results will likely bolster efforts to make financial education more widely available, if not mandatory, in schools across the country.