The One Book All New Parents Really Need to Read

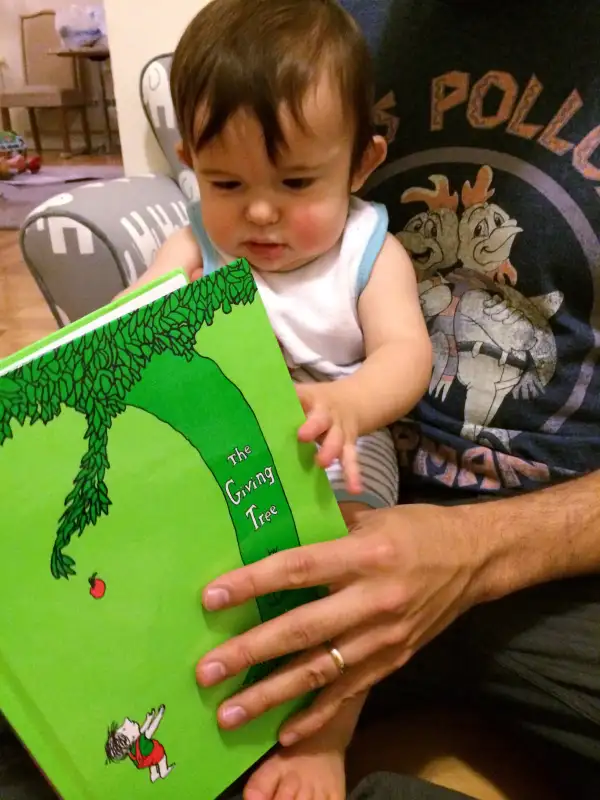

I try to read one book a day to my son, Luke—which works slightly better in theory than practice.

Luke's a restless infant, who is as eager to sit still in my lap for 10 minutes as he is to fall asleep. So I spend as much time reading as I do extending the pages beyond his grasp. Often he simply bores of the exercise, and I'm left talking out loud to no one in particular.

One of my favorite stories to read on these occasions is The Giving Tree.

The tiny book—which turned 50 this year—is perhaps the most important book in my life. I've loved it ever since I was a boy.

I recently discovered, though, that my adoration of Shel Silverstein's classic is not universally shared.

What the Book Is About

For those unfamiliar, The Giving Tree is the story of a relationship between a tree and a boy the tree loves. At first, the boy and the tree engage in what everyone would consider to be a healthy relationship. He plays on her limbs, eats her apples, and sleeps in her shade—all of which makes the tree happy.

Nothing stays perfect forever, though, and as "time went by," their encounters changed. The boy started to grow up and wanted new things.

Rather than playing in her branches, he wanted money and a house and a boat to escape his life. The tree gives up her apples and branches and trunk for the boy's sake, rendering herself nothing but a stump.

Through it all, the tree is forever happy when the boy returns for his next request and willing to give anything she has. In the end, the boy uses her stump to sit on "and the tree was happy."

Why It's So Hated

When I told friends of my affection for the book, they were incredulous: How could I find meaning in a story where one character repeatedly and unrepentantly takes and takes from the other? Was I some kind of martyr?

My friends were not alone in their hatred for the book. In doing a bit of research for this column, I found that many academics and authors, liberals and conservatives alike, find its supposed commentary on parenting distasteful, amoral and depressing.

Dr. Lisa Rowe Fraustino of Eastern Connecticut State University is among the haters. In an essay titled "The Rights and Wrongs of Anthropomorphism in Picture Books," she writes:

"Representing the symbolic mother as a literal tree may be what makes so many readers blind to the conceptual metaphor staring us in the face: GIVING TREE IS WOMAN. Even if it’s true that patriarchal culture has traditionally cut woman down and used her up, assigning her to the role of mother with her only happiness being with her son, is that an underlying moral we want to keep imparting to young children? Is it ethical?"

A post in The American Conservative says:

"Human love simply doesn't leave its subjects 'spent' in this way; there is death, to be sure, but that’s not a consequence of love in the way that the tree’s destruction follows upon the boy’s exploitation of it."

An entry in the New York Times's Motherlode blog writes,

"Parenting should not strip and denude, but rather jointly fulfill. The parasitic part is supposed to end with pregnancy. After that the point is to teach a child to make his own way in the world."

In The New York Times Sunday Book Review, Anna Holmes, founder of Jezebel.com, wrote,

"Of course, maybe we’re just projecting, but to those who would say that Silverstein’s book is a moving, sentimental depiction of the unyielding love of a parent for a child, I’d say, learn better parenting skills.

Others claim that the book teaches kids to become narcissists—that the world is built for their taking, that they'll never have to grow up.

Shel himself simplified the book to its essence, but warned readers from thinking the book has a happy ending.

“It’s just a relationship between two people; one gives and the other takes,” he's quoted as having said.

In any case, apparently you're a naive sentimentalist if you enjoy the thing.

Why It Should be Loved

Like most times in life, I think I'm right and those that disagree with me are wrong. Those critics that see a dark tale are misunderstanding something fundamental to the nature of parenting.

The infantilization of "emerging adults" is a hot topic these days, as more Millennials decide to return home after college due to a difficult job market, historic levels of student loans and soaring housing prices.

Money recently published a long feature on the stress parents face supporting their kids into their mid-20's and on: Nearly three quarters of parents aged 40 to 59 said they’d helped support an adult son or daughter in the prior year. Half said they provided their child's primary means of support.

No parent wants to be a stump.

But with all due respect to the critics who say this is a book about kids taking advantage, I think they are missing the point. At the same time, those who say The Giving Tree exemplifies unconditional love undersell its depth.

When Luke was first born, my wife and I were scared. We weren't scared because we were now charged with caring for a human life (an alien experience to both of us), nor were we terrified that our lives would change forever (though they have.)

The scary thing was that we, of our own will, introduced something into the world that we loved so much. And that newborn would soon be an infant, then a boy, then a teenager and on and on.

Just as we've struggled to find ourselves, to carve out our own little piece of happiness in our nearly 30 years, so he would too.

When you consider the weight of that decision, when you realize that you've suddenly foisted the world's beauty and ugliness onto this tiny thing, that he'll have to reconcile it just as you did, you become scared. (And then he has a dirty diaper, and you move on.)

To me, the Tree does not represent mom or dad, so much as it symbolizes an aspect of parenthood. Parents are obviously more than stumps for their children: We have lives, hopes, dreams, disappointments completely separate and apart from the goings-on of our progeny.

But when it comes to them, when they must grow up and face the world head on as adults, we want to be there to give them apples and branches and anything else we have to make their struggle a little easier.

"The Giving Tree" is beautiful because it lets kids know they're never alone. I think that's why I loved it so much as a child.

And that's why I think all new parents should read the book. It will help you put the task before you in perspective.

Taylor Tepper is a reporter at Money. His column on being a new dad, a millennial, and (pretty) broke appears weekly. More First-Time Dad:

- Why You're Better Off With a Hard-Working Child than a Smart One

- How to Cook a Real Dinner for Your Family…and Finish Before 9 p.m.

- Why Work-Life Balance is Just as Impossible for Dads