Now the Fed Really Won't Raise Interest Rates

The Federal Reserve has two jobs: maximizing employment and controlling inflation. It's doing better on one front than the other.

To get a clear picture of that, all you have to do is look at two recent reports from the Labor Department. Two Fridays ago the monthly jobs report showed that employers added 255,000 jobs in July and have hired an average of almost 200,000 workers a month for the past three months. More importantly, wages—which until recently had barely budged since the recession—had grown 2.6% over the past year.

So the economy is taking off, right?

Well, not so fast. In a report today the Labor Department announced that inflation, or the cost of living, didn't increase in July for the first time in five months, and is up only 0.8% over the past 12 months because of low fuel costs. That might sound like good news—low prices means your money goes farther, right?—but in fact a modest amount of inflation is widely considered a sign of a healthy economy. That's why the Fed targets 2% growth in its preferred inflation gauge, which is released by the Commerce Department. Unfortunately, it's not expected to hit that level until 2018.

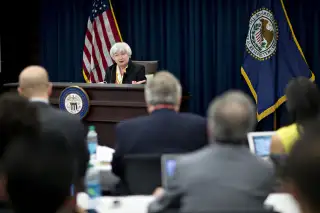

The Federal Reserve will meet in a little more than a month to determine whether the economy is strong enough, and inflation is enough of a threat, to raise interest rates for the first time since last December. That meeting is sure to be an interesting one, since the data is somewhat ambiguous.

On one hand, the nation is nearing full employment, with an unemployment rate consistently below 5%, and employers are adding to payrolls at a healthy clip. Hourly earnings are finally starting to pick up. It's even possible that inflation is accelerating faster than the Fed's preferred gauge registers: So-called core inflation, which strips out volatile food and energy prices, is up 2.2% since this time last year. And the Fed really doesn't want to miss the inflation train because it will be that much harder to slow once it gets going.

All that argues for an interest rate increase.

Further bolstering the case for higher rates is a practical consideration: Lowering interest rates is the Fed's primary tool for combating recessions—but the Fed can't lower interest rates if it doesn't raise them first. In the past eight recoveries, the Fed raised interest rates an average of 17 times before the next recession occurred, according to chief investment officer for LPL Financial Burt White. We are currently in one of the longest expansions in U.S. history, but the Fed has raised rates only once, by a quarter point, in December 2015.

On the other hand, the argument against raising rates is also compelling: The world economy simply is not growing very quickly. In the U.S., gross domestic product grew at an annual rate of only 1.2% in the second quarter of 2016. And Britain's central bank just cut rates in response to fears over poor economic performance thanks to the U.K.'s impending exit from the European Union.

That's why people like San Francisco Fed president John Williams are arguing that the Fed should increase its inflation target—in effect, that is should worry less about inflation and more about spurring growth. "Although targeting a low inflation rate generally has been successful at taming inflation in the past," Williams wrote in the central banks's recent Economic Letter, "it is not as well-suited for" the current low-growth environment.

Ultimately, concern about low growth will probably win out over inflation concerns—especially after today's inflation report. Wells Fargo Securities senior economist Sam Bullard says it will "allow the Fed to maintain patience with any potential policy normalization plans."

Fed officials started off the year talking about four rate hikes in 2016. Unless some rapid and unforeseen economic expansion suddenly appears, the next hike won't come until after the next president is sworn in.