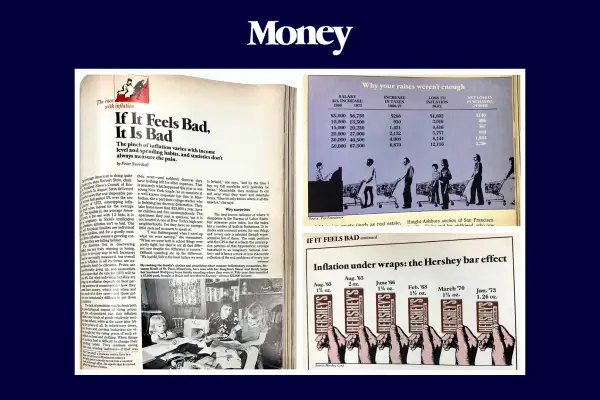

Money Classic: Inflation and the Case of the Disappearing Cash (1973)

Money is turning 50! To celebrate, we’ve combed through decades of our print magazines to uncover hidden gems, fascinating stories and vintage personal finance tips that have (surprisingly) withstood the test of time. Throughout 2022, we’ll be sharing our favorite finds in Money Classic, a special limited-edition newsletter that goes out twice a month.

This excerpt, featured in the third issue of Money Classic, comes from a story in our November 1973 edition.

Editor's note: This story includes language that isn't inclusive. Preferred language is always evolving, and Money is committed to writing stories that do not discriminate on the basis of race, color, sex (including gender identity and sexual orientation), religion, age or disability.

The average American is doing quite well, thank you, says Herbert Stein, chairman of President Nixon’s Council of Economic Advisers. In August Stein delivered the cheerful news that real disposable personal income had gained 5% over the second quarter of 1972, outstripping inflation — good news indeed for the average family. The trouble is, the average American family is the one with 1.2 kids; it is just as imaginary as Stein’s implication that, somehow, inflation isn’t so bad. The only real American families are individual American families, and for a goodly number of them inflation means a growing conviction that they are falling behind.

The dilemma lies in discovering whether you are truly winning or losing, and there is no easy way to tell. Increases in income are easily measured, but overall losses to inflation in all its forms are extraordinarily hard to calculate. Prices are unquestionably going up, and economists seem to agree that the rate for 1973 will be about 8%. But what individual families are giving up to inflation depends on their particular patterns of consumption — how they spend their money, where and when and how much of it they save — and those patterns are notoriously difficult to pin down in statistics.

The lack of precision results from both the psychological impact of rising prices and the oft-unnoticed fact that inflation makes some kinds of goods relatively costlier than others, while at the same time lifting the prices of all. In inflationary times, easy livers and careless budgeters are often caught by the rising prices of such essentials as food and clothing. When things go up they find it difficult to change their spending habits. They continue eating steak and wearing cashmere — if that was their wont — and suddenly discover that they have nothing left for other expenses. That is precisely what happened this year to one young New York couple, he an associate at a well-known corporate law firm in Manhattan, she a part-time college teacher who is finishing her doctoral dissertation. They take home more than $25,000 a year, have no children and live unostentatiously. The apartment they rent is spacious, but it is not located in one of New York’s high-rent neighborhoods. Yet they have no savings, little cash and no assets to speak of.

“I was flabbergasted when I toted up what we were earning,” she remembers. “When we were both in school things were pretty tight, but they’re not all that different now despite the difference in income.” Offhand spending ate up the difference. “We had $2,500 in the bank before we went to Ireland,” she says, “and by the time I buy my fall wardrobe we’ll probably be broke.” Meanwhile, they continue to eat and wear what they want and entertain freely. “Heaven only knows where it all disappears,” she says.

Subscribe to Money Classic here.