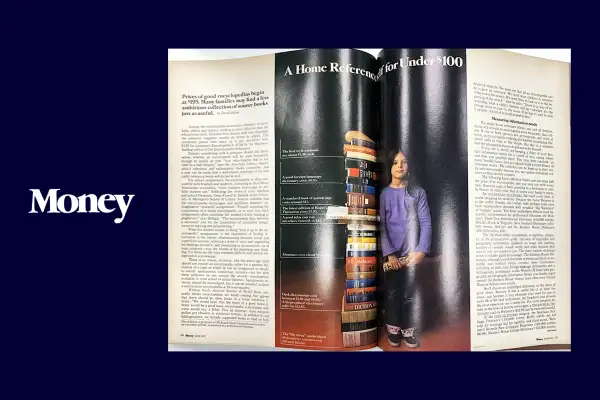

Money Classic: Don't Blow Your Budget on an Expensive Encyclopedia (1973)

Money is turning 50! To celebrate, we’ve combed through decades of our print magazines to uncover hidden gems, fascinating stories and vintage personal finance tips that have (surprisingly) withstood the test of time. Throughout 2022, we’ll be sharing our favorite finds in Money Classic, a special limited-edition newsletter that goes out twice a month.

This excerpt, featured in the ninth issue of Money Classic, comes from a story in our June 1973 edition.

Editor's note: This story includes language that isn't inclusive. Preferred language is always evolving, and Money is committed to writing stories that do not discriminate on the basis of race, color, sex (including gender identity and sexual orientation), religion, age or disability.

Among the encyclopedia salesman's collection of curve balls, sliders and sinkers, nothing is more effective than the educational pitch. Children from homes with encyclopedias, the salesman suggests, usually do better in school. The concerned parent often signs up to pay anywhere from $195 for Compton's Encyclopedia to $748 for the Heirloom-binding edition of the Encyclopaedia Brittanica.

Parents considering such a purchase should ask themselves whether an encyclopedia will be used frequently enough to justify its cost. "Any encyclopedia that is not used is a bad bargain," says the American Library Association's reference and subscription books committee, and a case can be made that a well-chosen collection of far less costly reference books will do just as well.

For school assignments, the encyclopedia is often misused by both teachers and students. According to the Library Association committee, "some teachers discourage or prohibit student use." Reflecting the views of many teachers and school librarians, Dean Russell E. Bidlack of the University of Michigan's School of Library Science contends that the encyclopedia encourages and facilitates teachers' unimaginative "research" assignments. "Usually requiring the consultation of a single encyclopedia, or at most two, such assignments often constitute the student's initial training in plagiarism," says Bidlack. "The encyclopedia thus becomes a necessary tool for the preparation of distasteful assignments in copying and paraphrasing."

What the student misses in doing "look it up in the encyclopedia" assignments is the experience of finding information in the library, discriminating between sound and superficial sources, selecting a point of view and organizing his findings around it, and presenting in an attractive — or at least coherent — way the results of his searching and thinking. Yet these are the very research skills he will need in college and in a profession.

There is no reason, of course, why the school-age child should not consult an encyclopedia, either for a general discussion of a topic on which he has an assignment or simply to satisfy spontaneous intellectual curiosity — but for both these purposes he can consult the several encyclopedias available in most school or public libraries. Spontaneous curiosity should be encouraged, but it can be satisfied without a multivolume encyclopedia on 24-hour standby.

William Nault, editorial director of World Book, naturally thinks encyclopedias are worth owning, but agrees that there should be other books in a home reference library: "We would hope that the heart of a good home library would be a good basic encyclopedia, a dictionary and, some would say, a Bible. Plus an almanac, since encyclopedias get obsolete in statistical matters. In addition to our bibliographies, we include suggested books to read on hundreds of subjects. We point out that all an encyclopedia can do is give an overview. We don't want children to consider it the end of the search. We want them to look on it as the beginning of the search." And he adds: "There is no way of anticipating what a child's interest will be — whether it's the energy crisis or man on the moon. If he has to wait to look it up later, it's not of as much import to him."

Subscribe to Money Classic.