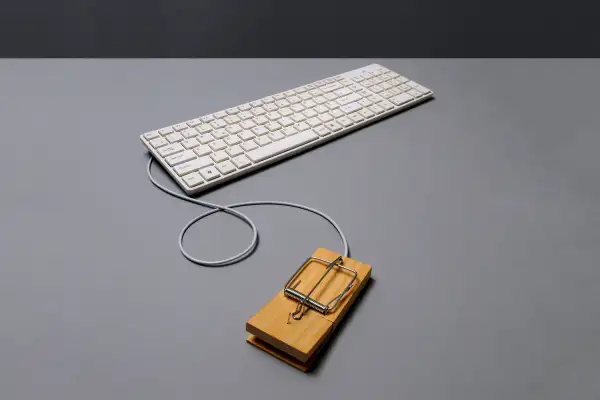

The Science of Why We Fall for Scams That Are So Obviously Scams

Peter, a retired lawyer, still can’t believe he was scammed out of $2,000, under the premise of keeping his step-grandson out of jail. “I’m much too smart for that sort of thing,” he said.

Except that, obviously, he wasn't.

Intelligence alone isn’t sufficient protection from a scam. Anyone with a heart, with a family, or with common desires or insecurities can be victimized by the sophisticated mind games used by today’s fraudsters.

Americans were scammed out of $1.7 billion in 2014 according to the FTC. Last year the FTC received more than 3 million fraud complaints, and it's been estimated that there were a least another 3 million victims who didn’t report their losses.

Peter, one of the many people I interview for my research as a consumer psychologist, spent a lot of time trying to figure out how he was conned. “In retrospect I can see that I just kept filling in blanks and making assumptions instead of challenging what I was hearing,” he told me. That’s something we all do—especially in stressful situations. We pay attention to information that supports our beliefs and ignore what doesn’t. Peter’s scammers had a good idea that he would make these kinds of cognitive errors. Their expertise in amateur psychology is the foundation of their success in ripping people off.

In order to protect yourself, it's wise to understand exactly how people get played. Here are some common scenarios that leave consumers especially vulnerable to scams:

Desperate Desire

People who are lonely or eager to make a quick buck are highly likely to fall for online dating scams and money-winning scams. For example, one older woman named Elaine sent more than $10,000 to a man she’d never met before her her family found out. The scammer found Elaine, a lonely widow who hadn’t dated for four decades, yearned for romance, and had little experience with social media, through Facebook. After a few “sweet” messages were exchanged, they began talking over the phone. Within six months the scammer had convinced Elaine to send two MoneyGrams, ostensibly to cover hospital expenses for his son, and so that “they could be together.”

Read Next: The Science of Why We Buy Clothes We Never Wear

When people feel like something they desire deeply is impossible to possess through their own efforts, they are especially susceptible to believe that destiny or some magic stroke of luck will come to the rescue. The technical term for this scenario is “external locus of control,” and the hallmark is a belief that nearly everything that happens in life is beyond one's personal control. When you feel this way, you're apt to put your fate in the hands of another person—like a mysterious Facebook suitor or a Nigerian prince with loads of cash.

Tech Support for Those Who Need It Most

What do the IRS, computers, and our legal system have in common? They’re murky. Most people don’t understand how they work. But they do understand the potential consequences of a misunderstanding are high. That’s why when a scammer calls to “fix” a computer problem or “help with” a neglected court summons, many people stop and listen. What they hear is horrifying: Jail sentences, dead computers, or massive fines are in their future if they ignore the scammers' "solutions." Panic sets in, prompting instinct to override rational thinking. The natural urge to avoid loss, blame, and shame also kicks in, and people feel compelled to want to make the supposed problem go away as quickly as possible.

I once walked right into the middle of such a scam. I heard screaming as I approached a home where I was scheduled to conduct an ethnography. Inside, the home's teenage son was horrified that his mother wouldn’t agree to give someone on the phone $350 to “fix” their computer. Millennials have a deserved reputation for being more tech-savvy than older generations, but they are actually more likely to be victims of tech support scams than any other group. This could be because of their youth and naivete, but also due to how attached millennials are to technology: For them, the prospect of a dead computer is especially urgent and devastating.

People with limited knowledge of technology—and who therefore lack confidence when troubles arise—are also likely victims because there's a tendency to trust anyone who seems to know more you do. In this scenario, it's easy to believe that fraudsters are saving you, rather than scamming you.

Read Next: The Science of Why We Secretly Like to Get Angry with Bad Customer Service

“I’m not great on the computer,” Milly, an active senior who fell prey to a tech support scam, told me. “When he said he was from Microsoft I didn’t have any reason not to trust him.”

The Super Scammers

Some scams are so sophisticated they leave nearly everyone vulnerable. For instance, Tim wasn't gullible enough to bite on the first call he received about the warranty on his new car needing renewal. In fact, he resisted several calls from the same pitch person. But eventually, the scammer's in-depth knowledge about Tim led him to assume it couldn't be a scam. "She had so many details about my car and me that it seemed like it must be real even though I think I knew it wasn’t," Tim recalled. "The one that got me was when she said this was my final warning and that I was about to be completely exposed."

Indeed, the standard fraud playbook is to create a sense of urgency, which elevates emotions and decreases rationality. Scammers often warn of deadlines to force action. They don't want to give the potential victim time to think things over or discuss the situation with others.

Some scammers know that the soft sell can be quite effective too. Peter, the lawyer mentioned at the beginning of this piece, said that one of the things that made him believe that his step-grandson really was in jail and that $2,000 would bail him out was the scammer's low-key, low-pressure tone. “He presented himself as helpful, like he didn’t really care if we sent the money and he was just there to help," Peter recalled. "He said, ‘It’s up to you, but the judge leaves at 4:30 so you have to decide by then.'”

Placing the decision directly in the victim's hands like the scammer did with Peter can be especially effective. It elevates a person's sense of responsibility. In this way, scammers take advantage of off our good nature. No one wants to be unkind or uncaring when family or friends are in need.

Read Next: Don’t Fall for the ‘Steve Martin’ IRS Phone Call Scam

Understanding how you are vulnerable is the first line of defense against scammers. But each of the scam victims I spoke with wished they’d taken one simple step to avoid getting conned. They all said they should have discussed what was happening with a sister, spouse, friend, or some other trusted ally. This truly is the best advice to avoid being victimized. It decreases emotionality, as you’re forced to relay the scenario in a rational manner. It provides you with a second—and hopefully logical—opinion, and it allows the would-be victim to get out from under the full sense of responsibility for the decision.

It also gives you more time to think, and perhaps Google the scenario that's been dumped in your lap. Your search may quickly reveal that it's a common scam.

Fraudsters are constantly thinking of new ways to con us, often using our most human needs, vulnerabilities, and inherent kindness against us. Let’s disappoint them. The next time someone calls from the IRS—which is itself a red flag, because the IRS never reaches out by phone—or when someone cold calls you and asks to remotely access your computer, ask if their mother knows that they steal for a living. Then hang up.

Kit Yarrow, Ph.D., is a consumer psychologist who is obsessed with all things related to how, when, and why we shop and buy. She conducts research through her professorship at Golden Gate University and shares her findings in speeches, consulting work, and her books, Decoding the New Consumer Mind and Gen BuY.