How Would Social Security Fare Under Trump or Clinton?

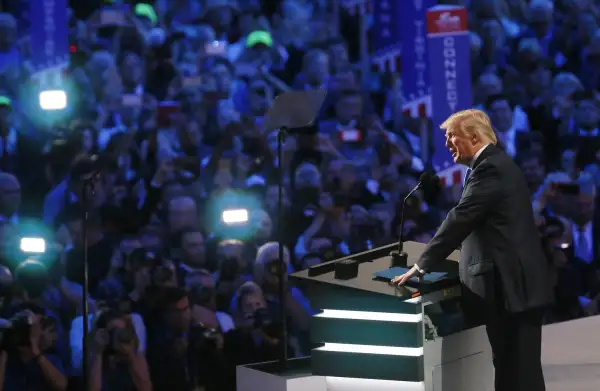

“Saving Social Security” is a sound-bite objective of both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump. With the Republican Party officially picking Trump as its nominee this week, it’s clear that saving the government program is defined differently by the Democratic and Republican presidential candidates. And in Trump’s case, there also may be a big gap between his views and those set forth in the Republican Party platform.

For now, seniors are awaiting more details. Trump has said publicly that he wants to preserve Social Security but has advanced no specific reforms. Instead, he suggests that strengthening the economy, reforming the tax code, and deregulating businesses will get the job done. The GOP platform contains only a single paragraph on Social Security:

Current retirees and those close to retirement can be assured of their benefits. Of the many reforms being proposed, all options should be considered to preserve Social Security. As Republicans, we oppose tax increases and believe in the power of markets to create wealth and to help secure the future of our Social Security system.

Clinton has gone beyond talk of preserving the program to proposing to expand it. She would seek to give family caregivers Social Security credits for their unpaid work and boost benefits for surviving spouses, most of whom are women.

Clinton would pay for these expansions, plus help restore Social Security’s longer-term financial health, by raising taxes on wealthier Americans. Her website says possible approaches include “options to tax some of their income above the current Social Security cap and taxing some of their income not currently taken into account by the Social Security system.”

As things now stand, Social Security is spending more each year in benefits than it receives in payroll taxes and earnings on its trust fund reserves. Those reserves are projected to be exhausted in 2034, according to the annual Social Security trustees’ report released last month. If this happens, the program would be able to pay only about three-fourths of the benefits to which people would be entitled.

A variety of steps have been proposed by others in Washington to address the gap. Raising the retirement age has received bipartisan support although liberals have lately backed away from the idea. The normal retirement age now stands at 66 and already is scheduled to rise to 67, beginning in 2020 for people born after 1954.

There also has been support on both sides of the aisle for tweaking the methodology used to calculate annual cost-of-living adjustments for Social Security recipients that would make those COLAs less generous. Here, too, Democrats have shifted toward more expansionary proposals.

As more information becomes available on the candidates’ Social Security proposals in coming months, an indication of their impact on the system may be available from an interactive Social Security tool that was recently developed by the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania.

It allows users to change any of six major program features--with three possible changes to each--and see how program finances are affected.

The six adjustments are:

- Raising payroll taxes, which are now 12.4% of payroll (half paid by employees and half by employers);

- Increasing the annual wage ceiling on which payroll taxes are paid, which now stands at $118,500;

- Basing the annual cost-of-living increase on a less-generous measure of consumer prices than is now used;

- An across-the-board benefit increase or decrease;

- Reducing benefits for higher-paid earners;

- Raising the normal retirement age.

The tool uses extensive population modeling to help predict how people would respond to possible program changes. The Wharton model predicts Social Security will run short of funds in 2031, three years earlier than the trustees’ project but comparable to estimates from the Congressional Budget Office.

For any proposed change, the tool will project the impact on a half dozen measures of program health. I used trust-fund reserves as my litmus test in experimenting with the Wharton tool.

On the Republican side, honoring the party’s pledge not to raise taxes rules out changing the income ceiling subject to payroll taxes or the tax rate. Changing the COLA next year, cutting higher-income benefits by a moderate amount, and raising the normal retirement age to 70 would extend program solvency by only two years.

Cutting benefits by 15% would, all by itself, extend to 2049 the point at which reserves would be exhausted. Unfortunately, the Wharton tool does not permit smaller benefit changes, which are a more likely response to program shortfalls. And it’s also not possible with the tool to limit the reduction to workers who aren’t close to retirement age, a provision that would honor the GOP platform on protecting pre-retirees.

For Clinton’s plan, I increased the annual cap on payroll taxes from $118,500 to $250,000. This buys about four years of solvency, to 2035. Also modestly reducing benefits to higher earners gains nothing additional. There just aren’t enough of them to move the needle for everyone.

Making these changes and raising overall benefits by 15% would, however, bankrupt the trust fund by 2027--four years earlier than the Wharton status quo projection. Even if the tax cap was raised to $400,000 year, a big benefit boost still would bankrupt the fund by 2028. (In the real world, smaller benefit changes would be more likely, so it would be nice if Wharton could provide them in the tool.)

Philip Moeller is an expert on retirement, aging, and health. He is co-author of the recently updated New York Times bestseller, “Get What’s Yours: The Revised Secrets to Maxing Out Your Social Security.” His companion book, “Get What’s Yours for Medicare: Maximize Your Coverage; Minimize Your Costs,” will be published this fall. Reach him at moeller.philip@gmail.com or @PhilMoeller on Twitter.