Stocks Are Rallying as President Trump Pushes to Reopen the Economy. But Can the Bull Market Really Last?

Money is not a client of any investment adviser featured on this page. The information provided on this page is for educational purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. Money does not offer advisory services.

It seems like a contradiction in terms: Death tolls and jobless claims keep rising...and, for the most part, so has the stock market.

Can the bull market really continue? ‘Yes,’ say some stock market strategists, but only if everything goes right.

More than a month after the U.S. began shutting schools and offices in an attempt to halt the spread of COVID-19, much of the economy remains on lock-down, with unemployment lines at their longest since the Great Depression.

Meanwhile, the Dow Jones Industrial Average is 25% above its mid-March lows, and, at around 23,000 is within 22% of its all-time highs. That's despite recent jitters tied to problems in energy markets.

Now, a growing contingent of Wall Street strategists, led by influential brokerage Goldman Sachs, are saying that at least some recent gains may hold, as long as there are no false starts in the ongoing effort to reopen the global economy or a second wave of Covid-19 infections.

But, they caution -- that’s a big ‘if’.

What the bulls see

The bulls’ thesis is that the economic outlook for the balance of the year is grim, but not as grim as it was in mid-March. Social distancing has slowed the spread of the virus in the hardest hit nations and states. A multi-trillion dollar stimulus effort from the Federal Reserve and the U.S. Congress “precluded the prospect of a complete economic collapse,” said Goldman’s strategists in a research note last week, revising what had been a bearish position on the near-term course of the stock market.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration, major employers such as Boeing and Apple, and state state officials such as Texas Gov. Greg Abbott are all pushing to start reopening the U.S. economy.

“The rally we’ve seen so far is reasonable given the market’s gone from pricing in an economic free fall with no sign of ending to seeing an ‘end-in-sight’ and thinking about the timing of reopening,” says Jeffrey Kleintop, chief global investment strategist at brokerage Charles Schwab.

What comes next

Despite the hopeful signs, Kleintop remains cautious. “That was the easy part,” he says.

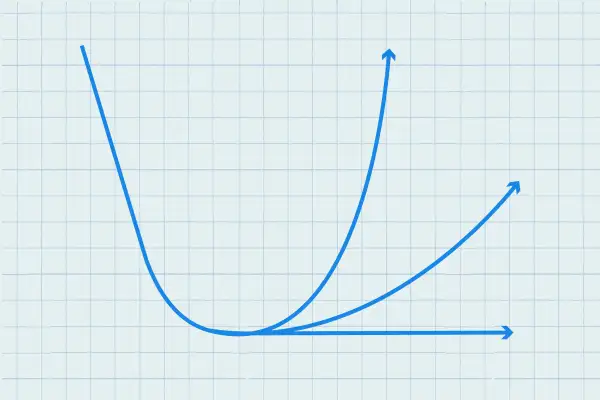

Now that the stock market has priced in a reopening, the hard part will be gauging “the shape of the economic recovery,” according to Mr. Kleintop and other strategists. Will it be “L-shaped,” the kind of multiyear recession that hollowed out the global economy a decade ago? Or will it be “V-shaped,” the kind of barnstorming comeback that happened after the 1998 Russian debt crisis?

Strategists at brokerage Barclays are among those who forecast a third option, a slow “U-shaped” recovery, as a lack of widespread testing makes the U.S. reopening a halting, tentative process.

Even in the best-case scenario, of a “V-shape,” U.S. second-quarter gross-domestic product growth would shring by as much as 35% (on an annualized basis), wiping out earnings growth for Standard & Poor’s 500 corporations. Growth expectations for 2020 would not be fulfilled until 2021.

The difficulty in assessing the outlook beyond the second quarter is reflected by the kinds of analysis that Mr. Kleintop and others on Wall Street are resorting to. In addition to the universally weak profit-and-loss statements and economic data, Mr. Kleintop is scrutinizing satellite camera images of Vienna rush-hour traffic (back to 50% of pre-coronavirus levels Tuesday!) and case counts in Denmark.

Others are watching air-quality data from China, taking a counterintuitive stance, says Quincy Krosby, chief market strategist at Prudential Financial. As the air grew dirtier in April, traders were taking “solace” that China’s factories and automobiles were coming back into action, Ms Krosby says.

“If we start to see, as people interact again, a rise in some of the new cases in some of these countries that have reopened that’s probably the worst-case scenario…that delays reopening in the U.S. or other countries and creates a ‘w-shape,’” said Mr. Kleintop.

The danger of aftershocks

Other analysts foresee a painful “w-shaped” recovery because they worry, even without another spike in Coronavirus cases, damage caused by moth-balling large sectors of the economy will create unpredictable aftershocks.

According to this theory, the stock market has absorbed the “first order” effects of COVID-19 – the medical emergency and the temporary freeze in income and consumer spending. The end of those events is, arguably, in sight.

But the ripple effects are just beginning – the oil crash that could easily bury major American shale producers; the likely bankruptcies of sprawling bricks-and-mortar chains such as JC Penney and, potentially, Neiman Marcus; the changes in human behavior that could transform the airline and cruise line businesses. The fiscal stimulus and tax-roll depletion could cause sovereign debt crises, particularly in countries such as Italy.

And any major bankruptcy or sovereign-debt crisis could have ripple effects of their own.

“The market is focused on the temporary aspect of the virus, ignoring the massive second round effects and the permanent damage to both the consumer and corporations,” said Lorenzo Di Mattia, manager of hedge fund Sibilla Global Fund. Di Mattia does not see the revival in earnings growth that the stock market has priced in for 2021.

Even those, like Joe Kinahan, chief market strategist at TD Ameritrade, who see markets as gradually stabilizing, are not predicting a smooth ride for the balance of the year.

“I find it hard to believe it’s going to be straight back up, ‘dingdong the witch is dead!’”

More from Money:

You're Probably Terrified to Look at Your 401(k). Here's Why It Might Not Be as Bad as You Fear

Investors Are Losing Interest in Active Mutual Funds. So Why Do Fund Companies Keep Launching More?