True or False: Ignoring the Census Could Cost You $5,000

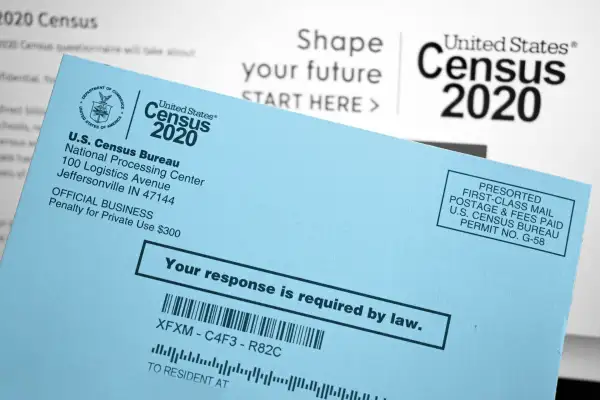

Every decade, the Census Bureau sets out to count every single individual in the United States.

An accurate count is important: It guides public funding decisions and helps determine how many congressional representatives each state gets.

Web and mobile response options that rolled out this year were supposed to make things easier, and lead to a better response rate. But the COVID-19 pandemic has forced the bureau to push back the deadline, and completely rethink how it will resume operations. Now, experts worry the pandemic could affect the accuracy of the nearly 250-year-old population survey, and lead to an inaccurate distribution of resources.

Data from the census impacts how $1.5 trillion of funding gets spent, says census expert and consultant Terri Ann Lowenthal.

“You can’t overstate the importance of responding to the census and helping ensure your community has an accurate count,” she says. “We have to live with the results for the next 10 years.”

There are a lot of questions up in the air right now. When is the census actually due? How will census takers go door-to-door amid a global pandemic? Can you get fined for not taking it?

Here’s everything we know so far.

How has the coronavirus impacted the census?

Thomas Wolf, an attorney with the Brennan Center who specializes in the census and redistricting, says the early phase of census operations has been significantly disrupted by the pandemic, and the timeline going forward is already shifting.

While the majority of the country has the opportunity to self-respond online, by phone, or through the mail, Wolf says the Census Bureau still relies on door-to-door counting in some parts of the country, including rural areas and Puerto Rico. And the pandemic has thrown a wrench into that effort.

The Census Bureau planned to have a 60.5% self-response rate by early May, Wolf says. But as of mid-month, only 56% of the country had responded, and less than 50% had responded in rural states like Montana and Wyoming.

Looking forward, Wolf predicts issues with getting an accurate count in low income areas, which tend to have less WiFi access, if COVID-19 prevents census takers from going door-to-door for much longer.

“There’s a ceiling on how many people can self-respond if the bureau can’t help by going door to door, and that ceiling is far too low,” he says.

When is the census due?

“Census Day” was originally scheduled for April 1, 2020, but according to the latest information from the Census Bureau, we now have until October 31, 2020 to respond online, on the phone, or through the mail. The bureau was initially planning to start the door-to-door knocking phase for those who haven’t responded by May, but that’s now been postponed until August, Lowenthal says.

The bureau is also still trying to figure out how to continue door-to-door operations given the public health risk posed by COVID-19, Wolf says. What’s most important now, he says, is for public citizens to ease that burden by self-responding as soon as possible.

“The number one variable that will determine how complicated, expensive, and labor intensive the census is going forward is the number of people that self-respond,” he says. “The fewer door knockers needed, the less likely it’ll be impacted by the pandemic.”

What if I don’t do the census?

According to information from the Census Bureau, it’s against the law not to complete the census. If you don’t fill it out, or if you answer any question incorrectly on purpose, you could theoretically face a penalty of up to $5,000. Experts say it’s unlikely you’ll actually have to dish out thousands of dollars to the Census Bureau if you don’t respond — but you should still make it a priority.

The Census Bureau isn’t a law enforcement agency, so it can’t directly penalize people who don’t participate. Instead, Lowenthal says, the bureau uses a “carrot over the stick approach” to promote participation. “The bureau wants to convince people that being counted is in the best interest of their family and their community,” she says.

The real risk that comes from not responding to the census is the lack of funding and political representation it can cause, says Kristen Seefeldt, an associate professor at the University of Michigan’s Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy.

“Inaccurate counts could lead to some communities that need funds not getting them, especially lower income, immigrant, and rural communities,” she says.

More from Money:

A State-by-State Guide to Getting Pandemic Unemployment Assistance Benefits

Are Cities the Source of Your Next Stimulus Check?

The IRS Says You Can Call This Phone Number and Talk to an Actual Person About Your Stimulus Check