Supreme Court Says Using Race in Admissions Decisions Is Fair Game

Affirmative action has survived another court challenge, after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 4-3 on Thursday that the University of Texas-Austin's consideration of race in admissions was legal.

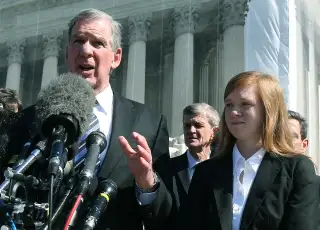

The case, Fisher v. University of Texas-Austin, stems from 2008, when Abigail Fisher was rejected by the university. She claimed it was because she was white. The university said it was because she wasn't academically qualified.

Texas has a unique admissions policy known as the Top 10 Percent Plan, in which the highest-ranked students at every high school are automatically admitted into a public university. The University of Texas-Austin fills the majority of its class through that plan, but for the last slice of the class, it uses a “holistic review” of individual applicants, which includes considering their race along with other achievements and experiences.

Court precedent allows universities to consider race as one of several factors in evaluating a student, but only if the university has no way of achieving diversity without considering race. That, in part, is what the court was evaluating in Fisher, since Texas's segregated high schools means that some level of diversity is achieved through its percentage plan.

When the case was heard in December, many observers predicted it might result in stricter rules around the legal use of affirmative action, if not the end of affirmative action altogether. But after Justice Antonin Scalia's death in February, the court's future decision was less certain. In the end, Justice Anthony Kennedy sided with justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor, and Stephen Breyer. (Justice Elena Kagan recused herself.)

Kennedy wrote in the majority decision that universities should have "considerable deference" in defining the importance of diversity and when the student body has reached that level of diversity. Even with Texas's Top 10 plan, only one in five undergraduate classes had more than one black student enrolled, and 12% of those classes didn't have any Hispanic students.

"Though a college must continually reassess its need for race-conscious review, here that assessment appears to have been done with care, and a reasonable determination was made that the university had not yet attained its goals," Kennedy wrote.

Thursday's decision ends Fisher's years-long run in the courts (this is the second time the case reached the Supreme Court), but it's not the end of the legal debate over race in admissions. Eight states have rules, often laws passed by voter referendum, which prohibit the consideration of race in admissions to public colleges. (They are Arizona, California, Florida, Michigan, Nebraska, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, and Washington.) And as the Chronicle of Higher Education notes, the same advocacy group that backed Fisher has filed separate lawsuits against Harvard University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill that take aim at race-conscious admissions.

Almost 30% of four-year institutions consider race in admissions, and 60% of the most selective colleges do, according to a recent survey by the American Council on Education. The practice is slightly more common at private colleges than public ones. Still, many colleges have begun moving away from race-based policies or at least supplementing them with policies that focus on socioeconomic factors, in what is known as class-based admissions.