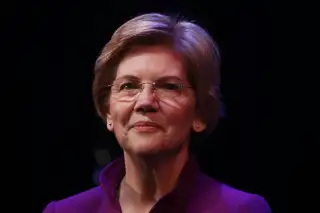

Elizabeth Warren Just Unveiled a Plan to Provide All Families With Child Care That’s Affordable — or Even Free

Democratic presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren unveiled a sweeping universal child care proposal Tuesday that aims to eliminate or lower child care costs for millions of Americans and increase the quality of child care providers — all with funding from her proposed tax on the ultra-rich.

Under the Massachusetts senator's new proposal, no family would spend more than 7% of their income on child care costs, and families who earn 200% or less of the federal poverty line (around $50,200 a year for a family of four) would have free access to child care.

Using federal funds to subsidize child care facilities, the proposal also aims to improve the quality of child care and early education programs to provide better salaries for these employees and ensure more children have access to higher quality programs that would "put them on track to fulfill their potential," Warren says.

The plan itself creates a public option for child care, using government funding while maintaining control on the local level through a network of center- and in-home child care providers, thus creating a national standard for child care. The initiative would cost an estimated $70 billion a year — and Warren says it would be funded by her proposed "wealth tax" on Americans who earn $50 million or more a year.

The child care proposal is the latest in Warren's progressive agenda which targets, in part, wide-ranging economic issues and corporate responsibility. The senator is the first of the crowded 2020 Democratic field thus far to propose universal child care as part of her platform — though others have proposed plans to help working parents and their children, too.

Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand has proposed a federal paid leave program, and Sen. Cory Booker has proposed creating "baby bonds," which would give children in the U.S. $1,000 in an account that would grow into several thousand dollars by the time they turn 18. Sen. Bernie Sanders, who announced his run for president Tuesday, proposed a bill in 2011 that aimed to provide all children "ages 6 weeks to kindergarten, with access to a full-time, high quality, developmentally appropriate, early care and education program."

The Trump administration has also addressed on the issue of high child care costs through the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, doubling the Child Tax Credit to $2,000 per child and expanding the benefit to wealthier Americans.

Money spoke with two economists who explained the potential impact of Warren's universal child care proposal. Here's what they said — and here's how it would work.

Eliminating and lowering child care costs

The average American family spends 17% of their income on child care costs, according to economist Chris Herbst, an associate professor at Arizona State University whose research focuses on child care and welfare policies.

That percentage varies largely from state to state, of course. Separate data from the Economic Policy Institute shows that child care in Massachusetts and Oklahoma, the state Warren represents in the Senate and the state she grew up in, eats up 19.5% and 13% of a family's income, respectively.

Even with the wide range, these high percentages show how unaffordable child care really is, economists say. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services says child care is affordable if it costs 10% of a family's income — and Warren's proposal takes that a step further, aiming to cap expenses at 7% and eliminating costs entirely for families earning less than 200% the federal poverty rate.

Spending so much on child care has limited not only the quality of care children can receive, but also the ability for parents to keep their jobs. That's particularly important for families who have felt the brunt of decades of slow wage growth. "We have seen very little gains in the last three or four decades in terms of families getting ahead, so it’s becoming more imperative for some children to be supported by two full time working parents," says Elise Gould, a senior economist at the Economic Policy Institute.

"If childcare costs are too high, [parents] may elect to just drop out of the labor force altogether," adds Herbst. "It hurts families budgets, hurts economic growth, and tends to hit women's labor force participation decisions harder than men's."

Eliminating or lessening the cost for child care can open the door for families to spend elsewhere or save more, economists say.

A policy funded by her proposed tax on the ultra-rich

Transforming the child care system comes with a hefty $70 billion price tag. But Warren says this policy could be funded by her proposed tax on the wealthiest Americans.

Introduced in January, the proposal includes an annual 2% tax on each dollar Americans who earn $50 million or more make, and a 3% tax for those who earn over $1 billion. That impacts around 75,000 households around the country, and would generate $2.75 trillion over 10 years, Warren says. "That's about four times more than the entire cost of my Universal Child Care and Early Learning plan," Warren says in a press release. Using this tax to fund this proposal avoids the possibility of increasing the deficit, Warren argues.

"It's certainly true that you have to make a sizable investment to tackle this problem," says Gould, of the Economic Policy Institute. "It's so widespread."

An emphasis on better quality and better funding

Being able to afford child care is one thing. But being able to afford high-quality care is a whole other issue, Warren argues.

It's a difficult balancing act for child care providers to ensure not only that their services are affordable, but also that their employees are being paid well.

"You have to handle both issues at once — access and affordability, and at the same time making sure you’re paying teachers well to get high quality they want," Gould says.

Part of the proposal includes paying child care providers similar wages as those received by public school teachers. Child care providers and daycare workers earn around $9 to $10 an hour on average, according to estimates from PayScale. With more funding, providers can create higher standards for their staffing, provide an education-based curriculum, make more services available to children, and hone in on intellectual development, Herbst, the ASU professor, says.

"There's far too little discussion about how poor childcare quality can be in the United States," Herbst says. "That has to do with how teachers are paid, the kinds of teachers that are attracted to child care employment, how child care programs are regulated, and the sorts of staff requirements teachers are held to."

"At the end of the day, those aspects are more important than subsidies," Herbst adds.