Hillary Clinton Has Managed Her Estate the Way She Does Everything Else

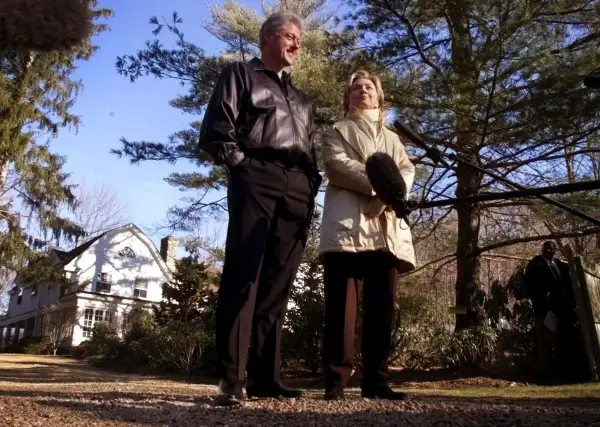

Democratic presumptive presidential nominee Hillary Clinton's campaign has been widely characterized by her pragmatism, caution, and meticulous preparation. Such extensive planning may be seen as either positive or negative in a candidate -- but there is no denying it is an asset when it comes to managing finances.

And Clinton's most recent financial disclosure form -- released in late May -- shows that she and her husband, Bill, have applied that same detailed forethought to their estate planning. Through the establishment of property and insurance trusts, the couple has employed tax strategies that ensure that, after they die, at least some of their millions of dollars in assets will be shielded from the estate tax. That tax is currently levied on estates of more than $5.45 million per person, or $10.9 million per couple; anything above that is taxed at rates that start at 18% (for the first $10,000 above the threshold) but rise quickly to 40%.

The irony: Clinton has taken these steps even though she has made public her own hopes for reforming the tax code, proposing a change to that would lower the estate tax threshold to $3.5 million and raise the top rate to 45%.

- Read More: Bernie Sanders Is a De Facto Millionaire

What the Clintons Are Worth

Clinton's revised rules would likely take a bigger bite out of her own estate, presuming the duo will have an estate worth much more than the exemption at the time they die.

The couple currently holds investments valued at between $10 million and $50.1 million, according to the disclosure forms. They have between $5 million and $25 million in a Vanguard 500 index fund, between $5 million and $25 million in a JP Morgan account, and between $50,000 and $100,000 in U.S. Treasury notes. (The federal forms allow candidates to declare assets within wide brackets, making more precise numbers hard to come by.)

In 2015, Hillary took home more than $5 million in royalties from her book Hard Choices, and $1.48 million in honorarium payments for speaking engagements, while Bill earned about $5.25 million in honorarium payments, according to Hillary's most recent financial disclosure form. Her 2014 tax return, however, showed that the couple's adjusted gross income was even higher that year at $27.9 million -- largely because the couple did more speaking engagements.

Real Estate Moves: Residence Trusts & Split Shares

Clinton's disclosures do not include the value of the couple's homes or retirement accounts, which do not have to be released. But while published reports suggest that the couple's real estate holdings are a smaller part of their net worth than their investment assets, their house is key to the couple's estate planning strategies.

One way the couple has chosen to limit the tax hit on their estate is via residence trusts, which prevent any growth in the property's value from being counted in the couple's estate -- and, therefore, from being taxed when passed along to heirs. "When you create these trusts, the benefit you're relying on is the appreciation down the road -- you're counting on it to grow into something much more valuable," says Michael Delgass, CEO of wealth management firm Sontag Advisory.

In general, residence trusts work by locking in the value of a home at the time it's transferred into the trust. If you expect your house's value to continue to grow, you move the home's ownership into the trust, and name the trust's beneficiary. When the trust expires, the home gets transferred to your beneficiary, and the size of your estate gets calculated using that earlier home value.

The Clintons established two such trusts in 2010, the disclosure form shows, and shifted ownership of their home in Chappaqua, N.Y., into them the following year. If the value of their home continues to grow, the move could save their estate hundreds of thousands of dollars in taxes, says estate planning and taxation expert Jonathan Blattmachr, who co-authored Bloomberg BNA's tax management book on personal residence trusts.

The Clintons bought the property for $1.7 million in 1999, and it had a market value of $2.3 million last year (four years after they moved the property into the trust), according to an estimate by Zillow for MarketWatch. When the IRS values the gift to the trust, however, it assumes the home is worth less than its present-day value, because heirs won't own it for some number of years -- typically 10 to 15, advisers say, although the length of a residence trust's term can vary widely. "The longer the term, the smaller the [value of the] gift," says Blattmachr. (The catch: Don't make the term too long, because if you die before the trust expires, the asset moves back into your taxable estate, and any appreciation counts against your estate tax exemption.)

In a move that reduces the Chappaqua home's valuation by even more, the Clintons also divided ownership of the house into separate 50% shares, with each share residing in its own trust, according to property records obtained by Bloomberg. That further discounts the value of an indivisible asset like a house, advisers say, because the whole is worth more than the sum of its parts, since neither could be sold independently for full value. Advisers say this strategy alone could easily cut the home's total value by another 15% to 30%.

The couple do own another home in Washington, D.C., estimated by Zillow to be worth $5.76 million, but they have not placed it in a property trust. Blattmachr says this could be for one of several reasons: The couple could think their D.C. home is unlikely to appreciate as much as their New York home, or they could intend to sell it, which becomes more complicated when inside one of these trusts.

Life Insurance Trusts

The disclosures also suggest that the Clintons aim to use life insurance as a key part of their estate planning strategy, both to defray future estate taxes and to pass on large sums tax-free to heirs, advisers say.

The couple holds five life insurance policies with a combined cash value between $1.28 million and $2.6 million. The cash value of a whole or universal life insurance policy at any given time is essentially the amount that has accumulated in the policy -- usually via investments or interest -- and that the insurer would pay out if the policy were canceled. The financial disclosure form does not specify what the death benefit of each of the Clintons' policies is, but financial advisers say it would likely be greater than the current cash value.

"It seems odd that they would continue to carry so much life insurance unless these policies are designed to transfer assets outside of the estate," says Lubbock, Texas, financial planner Brent Dickerson. "Typically, whenever your net worth is at the level theirs is, life insurance isn't really a must, because you’ve already got financial security. You don't need to protect your family from possible financial catastrophe if the breadwinner dies."

The couple hold three larger policies, two for Bill and one for Hillary: Two of those policies have a cash value between $500,000 and $1 million, while one is worth $250,000 to $500,000. (The Clintons also hold two smaller policies -- one in each of their names, and both valued between $15,000 and $50,000.) Each of the three larger policies is held in its own irrevocable life insurance trust.

In general, life insurance payouts to beneficiaries do not get taxed as income. But by placing the policies in the trusts, the Clintons have also taken the death benefits of those policies out of their estate -- meaning that money won't count toward the Clintons' estate tax exemption.

The move also allows heirs to use that life insurance payout -- rather than having to sell assets -- to pay the taxes the estate will owe, says Lake Oswego, Ore., financial planner Joe Alfonso.