Republicans Are Trying to Change the Way You Pay for Health Care. That's a Big Problem, a New Study Shows

Money is not a client of any investment adviser featured on this page. The information provided on this page is for educational purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. Money does not offer advisory services.

As Republicans in Washington work to overhaul America's healthcare system, they've given an outsize role to a fast-growing financial product known as the health savings account.

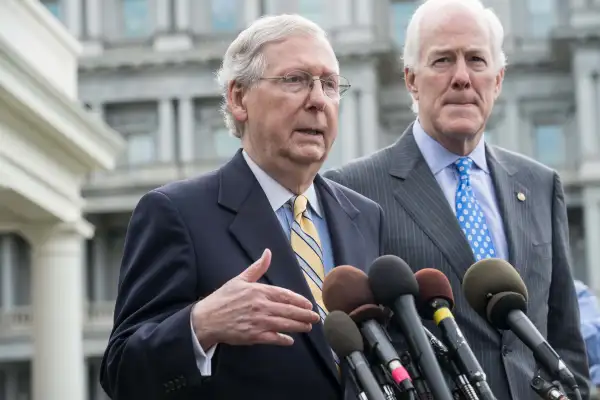

Both House and Senate versions of Republicans' Obamacare overhaul include provisions to greatly expand the use of HSAs, which deliver big tax breaks tied to health care spending. The idea is that these accounts encourage Americans to take more personal responsibility for their own health care costs, while also allowing them to put away money in the short term that can grow to offset medical costs later on.

The problem? Many of these accounts, typically offered by banks and credit unions, are riddled with high fees and mediocre investment options that blunt benefits to consumers, according to a new study from research firm Morningstar.

Often billed as health care's answer to the IRA, HSAs offer big tax savings -- designed to take some of the sting out of employees' out-of-pocket costs -- to Americans with qualifying high-deductible healthcare plans. Account holders get a triple benefit: They can contribute untaxed income, avoid capital gains and dividend taxes as contributions grow, and then spend money tax-free on qualified medical expenses.

Yet while HSA assets have swelled -- rising to $37 billion by the end of 2016 from less than $12 billion five years ago, according to Devenir, an HSA research and investment firm -- many of the large investment firms that dominate the consumer-facing retirement space (such as Fidelity, Schwab, and Vanguard) have remained on the sidelines. And among the 10 institutions that do offer popular, commercially available HSAs direct to consumers, Morningstar found only a single one that passed muster on both saving and investing fronts.

That raises questions about whether HSAs genuinely deserve an expanded role in Americans' financial lives. "You run the risk of nudging people into accounts that still have a lot of room for improvement," says Morningstar analyst Jake Spiegel.

While the HSA market can be opaque, Morningstar analyzed fees and investment options for what it estimated to be the 10 most popular HSA providers that sold accounts directly to individuals. The list included familiar names like Bank of America, as well as credit unions and specialty providers.

HSAs typically involve two components -- a checking account, which savers use to deposit and spend money, and an an investment account, where any money that is not spent immediately can be invested for future healthcare expenses. Only the HSA Authority got positive marks on both fronts from Morningstar.

One big problem: HSAs typically charge hefty maintenance fees -- often hitting account holders twice -- with one fee for the checking account and a separate fee for the investment account. On top of those, there also comes a third layer of fees, which account holders pay to invest HSA balances in mutual funds. The upshot is that with at least half of the providers, HSA investors pay estimated annual fees of 1.18%, Morningstar calculated -- roughly $177 on a $15,000 investment. To put that in context, it's more than twice what the mutual fund industry's main trade group says investors pay to invest in a typical 401(k).

There is one important caveat, notes Devenir co-founder Eric Remjeske, who has reviewed the Morningstar research: Not all HSA investors pay full freight. Morningstar's research is based on prices HSA providers offer to the public. However, the majority of HSA holders sign up for plans through employers, when they sign up for their company's health insurance plan -- and large employers frequently persuade HSA providers to waive some fees or pick them up on behalf of their employees, Remjeske says.

That said, many retail HSAs are as good or better than plans sold through employers, and account holders that do enjoy employer-sponsored perks may lose them when they switch jobs.