I Read Sen. Ben Sasse's Takedown of Millennials and It's Very Wrong

For the past few years, it would seem that Baby Boomers and Gen Xers have derived no greater pleasure than disparaging the millennial generation in any way possible, from mourning the industries they destroy, decrying their lack of character and decaying masculinity, pointing out their inability to get jobs and pay attention, and preaching about their selfishness and amorality.

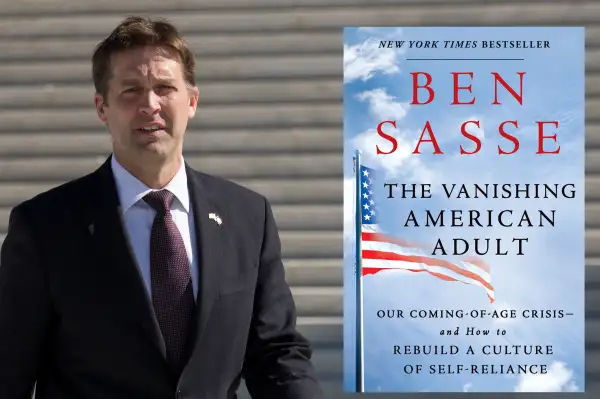

In that regard, 45-year-old Nebraska Senator Ben Sasse's book, The Vanishing American Adult, says nothing new—rather it compresses all of the standard Boomer complaints in a neat 263 pages, while ignoring all of the very real, structural problems that workers today face.

Disclaimer: I am a millennial. I have, at one point in time, used an air conditioner, a modern day contraption that Sasse says “breeds softness and entitlement." I post on the Social Medias. Regular paychecks since I was 16 suggest I'm not lazy, despite Sasse's assertion that young people no longer know the value of hard work.

So I had to fight several urges to throw The Vanishing American Adult straight into the recycling bin. Why? It is not, as many a Sasse may believe, because my attention span has been warped by countless days spent taking Buzzfeed quizzes, but rather because of his predictable diagnoses of the ills of my generation — tired, overplayed tropes that help older audiences, convinced that the kids are getting everything wrong, feel superior.

“How did we get to this point,” Sasse asks on page 18, “where a large portion of our people in the prime of their lives are stuck in a sad sort of limbo, ordering pizza on cell phones while streaming Netflix from their parents’ basements, where they live?”

It doesn’t get much more insightful than that. Sasse blames the usual suspects for all of these freeloading youngins using up ma’s WiFi: More video games, less marriage, less religion, a renewed interest in socialism, helicopter parents, and safe spaces.

Millennials are the Worst: Sasse's Argument

It turns out, a handful of personal anecdotes and cherry-picked Medium posts are enough to make sweeping generalizations about entire generations of people. According to Sasse, kids these days are soft and weak and ill-prepared for the future because he once witnessed some 18-year-olds at Midland University, where he was president, decorate only half of a Christmas tree. Worse still, his daughters said they “needed air conditioning” to sleep.

Sasse admits we are shifting to a knowledge-based workforce, but won't let go of the past, where you grew up working on the farm, got hitched to your high school sweetheart, and mom stayed home with the kids while dad went out and earned enough money to take the family to Disney World.

No disrespect to Mickey Mouse, but that type of idealized middle class family dynamic existed for few people in the U.S. in the good old days, and is even less common now.

To use that type of family and worker as the standard to which all young people should be held is to buy-in to the tired stereotype that there is but one type of millennial: A person that is oft-maligned for drinking soy lattes and eating avocado toast. A person that grew up earning participation trophies and taking piano lessons to add to their Ivy League applications. A person that is relatively privileged, likely white, and, ultimately, rarer than media coverage and Sen. Sasse's personal experiences would have you believe.

Reading Sasse’s book, you’d be forgiven for thinking no other type of millennial exists, because the Nebraska Senator appears to have forgotten about them. What advice does he have for the predicted 40% of the workforce that will be employed in gig economy jobs by 2020, with no hope for benefits like health insurance and company-sponsored retirement accounts? What does he have to say to those who have enlisted in the military? Or the 50 million Americans who live in communities boasting over 55% unemployment, or the 30% of high school dropouts who left school to work and support their families? Do they simply not exist, or are they not worthy of his advice to embrace hard work?

You see this total erasure of the vast majority of Americans (millennial and otherwise) in passages such as, “we seem collectively blind to the irony that the generation coming of age has begun life with far too few problems…” (emphasis in the original) or, “[t]he riddle before us is how to construct alternative ways of building long-term character in an era when the daily pursuit of food and shelter no longer compels it.”

Does the Senator know that one in six American children are undernourished, according to Feed America? That between 1979 and 2010, household disposable income for people aged 25 to 29 has stayed stagnate, according to the Guardian, while increasing for the rest of the population? That the wealthiest 20% of millennials earn eight times more than the other 80% of their generation, an unprecedented level of wealth stratification?

Millennials Aren't the Worst: Ben Sasse's Missing Point

Nowhere in The Vanishing American Adult does the Senator seriously take issue with the fact that, as the Guardian put it, “it is likely to be the first time in industrialized history, save for periods of war or natural disaster, that the incomes of young adults have fallen so far when compared with the rest of society.” There’s $1.3 trillion in student debt, rising home, healthcare, and childcare costs. The Senator is quick to complain about millennial laziness and entitlement, that they are putting off families and home ownership longer, but he is mum on the factors that could contribute to young people not only feeling less-than-optimistic about the economy, but contribute to them being structurally shut out of many of the gains to be made in it.

Sasse does offer some genuine insights. The lines between adolescence and adulthood have become increasingly blurred, and algorithms shaping the media and information we consume based on our past clicks is a real problem. We should all be lifelong learners, and embrace critical thinking, and focus less on material consumption. The chapter in which Sasse discusses the pitfalls of our public education system is a worthwhile read, if one-sided.

But the way forward is not to shame young people for snapping selfies and wish for a return to the work that the country was built on centuries ago. It is to ensure that they and other workers have the skills they need to succeed in the 21st century, and to dispense with the notion that a few focus group-tested statements can apply equally to 83 million+ people. To read this book is to assume that all young people enjoy upper middle class lives, with few cares in the world. And that says more about the author than the generations he is attempting to advise.