Money Classic: Predicting the Future of Work and Retirement (1985)

Money is turning 50! To celebrate, we’ve combed through decades of our print magazines to uncover hidden gems, fascinating stories and vintage personal finance tips that have (surprisingly) withstood the test of time. Throughout 2022, we’ll be sharing our favorite finds in Money Classic, a special limited-edition newsletter that goes out twice a month.

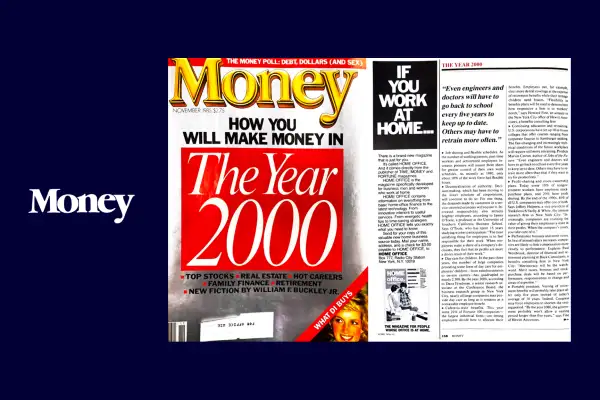

This excerpt, featured in the 16th issue of Money Classic, comes from a story in our November 1985 edition.

Editor's note: This story includes language that isn't inclusive. Preferred language is always evolving, and Money is committed to writing stories that do not discriminate on the basis of race, color, sex (including gender identity and sexual orientation), religion, age or disability.

Almost every aspect of your working life will be altered by the end of the millennium — and generally for the better. You'll spend less time in a more comfortable office, and you'll receive new custom-tailored fringe benefits. Your paycheck will be bigger, and though inflation and Social Security tax increases will undoubtedly cut into your buying power, performance bonuses will help make up the difference. And you'll retire earlier, though you probably won't stop working. More likely, you'll walk away from your company with a modest pension and set up your own business.

This brave new workworld will not spring from any sudden wave of corporate altruism but from the efforts of tough-minded business strategists to adapt to irresistible demographic pressures, rapid technological advances and aggressive competition.

By the turn of the century, the 76 million members of the postwar generation will have realized that they can't all have it all — and still squeeze into executive suites. As a result, those who aren't content to stay where they are will have to switch careers or start businesses of their own. But right behind this vast cohort is a smaller 41 million-member generation born between 1965 and 1976. This diminished labor pool will force firms to compete fiercely for the top talent, so companies will beef up benefits to make jobs more attractive.

Over the past 15 years, women have gone to work in ever larger numbers, and they now make up 44% of the work force. Says Harvard labor economist David E. Bloom: "That is probably the single most important change that has ever taken place in the American labor market." But this growth is largely over. By 2000, women will increase their labor force share by only two percentage points. They'll also win additional representation in top management as today's 35-year-olds gain business experience. Rand Corp. economist James P. Smith figures

that women will represent about 30% of top executives, compared with about 10% today. Women can also expect to earn more, but won't achieve equal pay with men. Women now earn 64% as much as men do; on average by 2000, says Smith, they will make 80% as much. More blacks are also likely to find their way into the ranks of business managers.

According to a report by the College Entrance Examination Board, the number of black students pursuing business and management courses is increasing, while studies in such fields as education and social sciences are declining. The proportion of blacks in college, however, has temporarily leveled off. And overall, the Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that

the number of minorities needing jobs will grow at twice the rate of whites over the next 10 years.

The next 15 years will bring a steady improvement in the nine-to-five lives of most workers. Eager to stay competitive, successful companies will want to find and retain the best employees. (For a look at how IBM does it, see page 165.) One way to keep workers happy without adding substantially to overhead is to offer some, if not all, of the following:

- Shorter working hours. The 40-hour week, the norm in the 1940s, has shrunk to 36.1 hours today and will continue to erode. Because of growth in service industry jobs that don't strictly adhere to fixed hours, the average workweek may drop to 34 hours by 1995.

- Job sharing and flexible schedules. As the number of working parents, part-time workers and semiretired employees increases pressure will mount from them for greater control of their own work schedules. As recently as 1980, only about 10% of the work force had flexible hours.

- Decentralization of authority. Decision-making, which has been moving to the lower echelons of corporations, will continue to do so. For one thing, the demands made by customers in a service-oriented economy will require it. Increased responsibility also attracts brighter employees, according to James O'Toole, a professor at the University of Southern California Business School. Says O'Toole, who has spent 15 years studying worker participation: "The most satisfying thing for employees is to feel responsible for their work. When employees make a share of a company's decisions, they feel that its profits are more a direct result of their work."

- Day care for children. In the past three years, the number of large companies providing some form of day care for employees' children — from reimbursements to on-site centers — has quadrupled to nearly 2,500. By the year 2000, according to Dana Friedman, a senior research associate at the Conference Board, the business research group in New York City, nearly all large companies may provide day care as long as it remains as a nontaxable employee benefit.

- Cafeteria-style benefits. This year some 22% of Fortune JOO companies — the largest industrial firms — are letting employees decide how to allocate their benefits. Employees can, for example elect more dental coverage at the expense of retirement benefits while their teenage children need braces. "Flexibility in benefits plans will be used to demonstrate how responsive a firm is to workers' needs," says Howard Fine, an actuary in the New York City office of Hewitt Associates, a benefits consulting firm.

- Continuing education and retraining. U.S. corporations have set up 18 in-house colleges that offer courses ranging from corporate finance to hamburger making. The fast-changing and increasingly technical conditions of the future workplace will require still more retraining. Predicts Marvin Cetron, author of Jobs of the Future: "Even engineers and doctors will have to go back to school every five years to keep up to date. Others may have to retrain more often than that if they want to try for promotions."

- Profit-sharing and stock-ownership plans. Today some 10% of nongovernment workers have employee stock-purchase plans, and 20% have profit sharing. By the end of the 1990s, 40% of all U.S. companies may offer one or both. Says Jeffrey Halpern, a vice president of Yankelovich Skelly & White, the opinion research firm in New York City: "Increasingly, companies are realizing the value of giving their employees a stake in their profits. When the company's yours, you take care of it."

- Performance bonuses and merit raises. In lieu of annual salary increases, companies are likely to link compensation more closely to performance. Explains Paul Westbrook, director of financial and retirement planning at Buck Consultants, a benefits consulting firm in New York City: "Meritocracy will be the watchword. Merit raises, bonuses and stock-purchase deals will be based on performance, responsiveness to change and areas of expertise."

- Portable pensions. Vesting of retirement benefits will probably take place after only five years instead of today's average of 10 years. Indeed, Congress may force employers to shorten the vesting period. "By the year 2000, the government probably won't allow a vesting period longer than five years," says Fine of Hewitt Associates.

As conditions for most workers improve, the nation's labor unions will continue to fade. Five years ago, 23% of all employed workers belonged to unions; this year, it's only 18.8%. Fast-growing service businesses are successfully resisting labor's entreaties, and many companies are voluntarily providing benefits that unions have fought for in the past. Says Jeffrey Hallett, president of Trend Response & Analysis Co. in Alexandria, Va.: "By the year 2000, union membership should be closer to 10% as the managements of egalitarian-style firms increase benefits and transfer more equity to employees through profit-sharing and stock-purchase plans."

Blue-collar jobs meanwhile are being lost ever more quickly to advanced automation techniques. Although industrial robots have not caught on as quickly as expected, some 18,000 are now at work in U.S. factories. Studies by Ramchandran Jaikumar, an associate professor at Harvard Business School, found that each robot replaces from one to five employees, depending on its sophistication and use, while one worker can operate two to 10 robots by himself. By 2000, the number of robots in fields such as manufacturing, toxic-waste disposal and food processing is expected to increase tenfold.

With so many blue-collar jobs vanishing, retraining will be essential. Some employees will have to learn new skills and change careers; others will have their skills upgraded, blurring the distinction between engineers and craftsmen. Asserts Peter J. Hubshman, executive vice president of DCTECH Research Centers, a Washington, D.C. high-precision-machine company: "We've found that quality increases when the traditional stratification of engineering and machining departments disappears."

In the office, some 10 million desktop computers are now used routinely, and industry analysts predict an increase to 30 million by the end of the century. The computerized office will be cleaner, cooler and quieter than its paper-and-pencil-laden predecessor, though workers will probably continue to complain about the lack of privacy afforded by open layouts and partitions that reach only partway to the ceiling.

Computers will intrude even further into the workplace as more companies turn to them to help decide whom to hire or promote. Successful companies, however, won't forget that the most creative employees are often those who don't fit the software profile. Hewlett-Packard in Palo Alto, Calif., for instance, presented an employee award for "meritorious defiance" recently to two employees. They pursued an idea against opposition from higher-ups and stuck with it until it was accepted.

One way to avoid the office of the future will be to work at home. Today as many as 25 million people do it, according to Electronic Services Unlimited, a New York City research and consulting firm. The number is expected to double by 2000. Employers have found that they can cut costs by letting workers stay away from the office. According to Jeffrey Hallett, companies save on average about $400,000 a year on office space when 100 employees work at home.

Numerous studies of how people work at home show a curious side effect: they miss the bustle and social interaction of the office. A possible compromise may be to rent space in a mini office park where many different professionals and entrepreneurs will work. Some will share their space and split the rent by working only two or three days a week.

Working at home creates another problem for the year 2000. Under pressure to produce and with a bonus hanging in the balance the worker will find that once he's able to work anywhere, he's working everywhere. Then the question will become when to stop.

Subscribe to Money Classic.