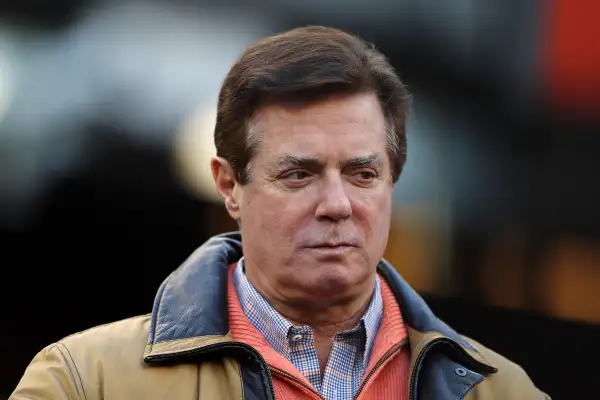

Paul Manafort Is Accused of Money Laundering. Here’s What That Means

President Trump's former campaign manager just got accused of something you usually hear about in gangster movies, "money laundering."

In an indictment unsealed Monday morning, Paul Manafort and his right-hand-man, Rick Gates stand charged with conspiracy to commit money laundering and conspiring against the United States, among other claims. The scheme, investigators claim, has been going on as far back as 2006. But how does one launder the $75 million that allegedly flowed from offshore accounts, as investigators claim?

At its simplest, money laundering is when you take the profits from an illegal activity and "launder them" to make it seem like they come from a legitimate source. For petty gangsters, that can mean running an all-cash side business like a pizza parlor or a dry cleaner that can be used to explain profits for loan sharking or running a sports book. Manafort is accused of operating something essentially similar but far more complex -- a network of offshore accounts, shell companies, bank accounts and seemingly legitimate businesses transactions.

In the case of Manafort and Gates, investigators claim that at least some of the laundered money started as payments from Ukraine—in particular the pro-Russian political party, the Party of Regions. The indictment alleges that both Manafort and Gates worked as lobbyists on behalf of the Regions party and its then head, Viktor Yanukovych, President of Ukraine (Yanukovych was elected in 2010, but removed from office in 2014).

The problem was that neither Manafort nor Gates registered to lobby on behalf of a foreign government, a process that requires submitting paperwork and a statement under oath to the Department of Justice. (The indictment doesn't specify why he wanted to avoid this.)

“In order to hide Ukraine payments from the United States authorities, from approximately 2006 through at least 2016, Manafort and Gates laundered money through scores of United States and foreign corporations, partnerships and bank accounts,” according to Monday’s indictment.

If that’s true, then the money they raised from the Regions party and related lobbying efforts had to be ‘washed clean.' Manafort and Gates did this by first funneling the money into offshore accounts in Cyprus, the Grenadines, St. Vincent and elsewhere, according to the indictment. Investigators claim that Manafort laundered more than $18 million through offshore accounts, while Gates transferred more than $3 million.

From there, Manafort used the money to make real estate purchases, spending $1.5 million to help purchase a $2.85 million brownstone in New York's fashionable SoHo neighborhood, as well as other million-dollar properties in Brooklyn and Arlington, Va.

Manafort also allegedly used these real estate properties as collateral to take out loans, a move which may have helped him convert his valuable real estate back into cash that he could spend, investigators claim. For example, Manafort took out a $3.2 million loan against the SoHo property in March 2016. (Manafort also allegedly lied on his mortgage application, claiming it was a secondary home for his daughter and son-in-law when in fact he was renting it out for thousands dollars a week as an Airbnb rental.)

In addition to buying real estate, Manafort and Gates used the offshore money, tax free, on a wide variety of personal expenditures, including clothing, antiques, home improvements, and even private school tuition for Gates’ children. Specifically, Manafort spent $5.4 million with a home improvement company in the Hamptons between 2008 and 2014, as well as $934,350 at an antique rug store in Alexandria and $849,215 at a clothing store in New York, according to the indictment.

The indictment didn't state whether prosecutors believe these payments amounted to lavish personal spending or part of a secondary effort to route more cash back to Manafort and Gates. However, overpaying for goods is another common way to launder money. “Overpayment for services is a very popular method of money laundering for good reason— it takes a very keen eye to notice, and is even more difficult to prove,” according to the Whistleblower Justice Network.

Investigators contend that Manafort, since 2008, spent at least $12 million from offshore accounts without paying any taxes on the income. And, according to the IRS, any income from whatever source derived (legal or illegal) is taxable.

In all, Manafort and Gates are facing a dozen counts ranging from money laundering to failing to file proper paperwork. Sentences for those convicted of money laundering can be as high as 20 years in jail and up to $500,000 in fines.