Social Security's Buying Power Has Dropped a Whopping 33% Since 2000. Here's What the Average Check Is Now

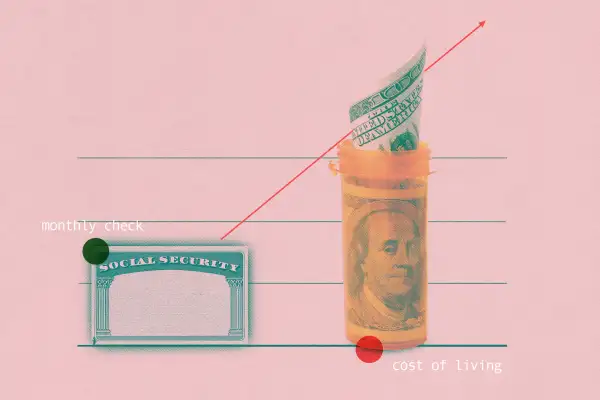

Social Security benefits have lost one third of their buying power since 2000, according to a report released Tuesday by The Senior Citizens League, a non-profit organization.

Retirees’ monthly benefit checks have not kept up with the skyrocketing costs of prescription drugs and other essential goods and services, resulting in a 33% drop in purchasing power.

Since 2000, typical expenses for seniors have risen twice as fast as the yearly cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) to Social Security, the report says. This annual raise is supposed to counteract the impact of inflation on Social Security, and while benefits rose 2.8% for 2019 (the highest increase since 2012), it is not enough to compensate for the mounting bills that seniors have to pay. The cost-of-living adjustment is based on increases in the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W). The bump to benefits was 2.0% in 2018, 0.3% in 2017 and there was no adjustment at all in 2016.

"Drugs, housing and food are rising at several times the rate of Social Security," says Mary Johnson, a Social Security and Medicare policy analyst at The Senior Citizens League, who authored the report. "What's stacking the deck are things like Medicare Part B."

Prescription drug prices have increased 253% since 2000 and Medicare Part B premiums have risen almost 200%, along with items like home owners' insurance and real estate taxes, according to the report.

The average monthly Social Security benefit in 2000 was $816.60 a month, and someone who collected that amount 19 years ago would have $1,226.60 today, thanks to the annual cost-of-living boost. But that still falls short: to retain the same purchasing power as $816 in 2000, the monthly check would need to be $1,634.50, according to the report. Meanwhile, the average check for all retirees is $1,461, according to the Social Security Administration.

This puts the 60 million Americans who collect Social Security at risk for a declining standard of living — particularly the more than two thirds who rely on Social Security as their main source of income.

Calculating the annual cost-of-living adjustment using the CPI-W may play a factor in Social Security's diminished buying power, according to Johnson. That measure of inflation tracks the spending habits of younger workers, but younger Americans have different spending patterns than retirees, and they don’t spend as much on healthcare costs — which are growing at a much faster pace than overall inflation.

Johnson believes a better way to offset inflation in Social Security benefits is by using the Consumer Price Index for the Elderly (CPI-E), which does track the spending of retired people age 62 and older; Congress would need to pass legislation to make any changes to the COLA calculation.

"As people live longer in retirement, their savings have to go a lot farther, and their Social Security benefits have to be adequate to last for 25 or 35 years," Johnson says.

She estimates the cost-of-living adjustment for Social Security in 2020 will be around 1.7%.