Here's What the Most Expensive Ticket on the Titanic Would Have Bought You

Even if it had dodged that iceberg 104 years ago today, the R.M.S. Titanic might still be remembered as the most luxurious ship of its time, perhaps of any time.

Costing $7.5 million in 1912 dollars to build and furnish—the equivalent of $180 million today—it spared no expense, except in the little matter of lifeboats.

While the second- and even third-class accommodations on the Titanic were a cut above what passengers might find on other ships, it was in first class that the White Star Line tended to go, let’s say, overboard.

So what did a first-class ticket on the Titanic buy you?

Consider the case of Charlotte Drake Cardeza, age 58, of Philadephia.

While not on the A+ list with other Titanic millionaires like John Jacob Astor IV and Benjamin Guggenheim, Cardeza was a yachtswoman, big-game hunter, and patron of the arts. The family fortune came from her father, a wealthy textile-mill owner.

Cardeza had no trouble affording what is believed to have been the most expensive ticket on the ship: $2,560 in 1912 dollars, or more than $61,000 today.

She boarded the ship in Cherbourg with her 36-year-old son, Thomas, her maid, and his valet. They also brought along 14 trunks, four suitcases, and three crates of other stuff.

The Cardezas occupied what was referred to as a three-room suite, with two bedrooms and a sitting room, plus two wardrobe rooms and a bath. Their servants were assigned to interior cabins nearby.

Their suite was one of two most luxurious aboard the ship. Its mirror-image counterpart would most likely have been occupied by the financier J.P. Morgan, who controlled the company that owned the Titanic, had he not backed out before the ship sailed.

The suite’s most unusual amenity was a private, 50-foot-long promenade deck. Not only could the Cardezas avoid the lower classes if they were so inclined, they didn’t even have to mingle with their fellow plutocrats.

Added all up, the Cardezas’ accommodations occupied the square footage of a small ranch house.

Related: How Bad Was Income Inequality on the Titanic?

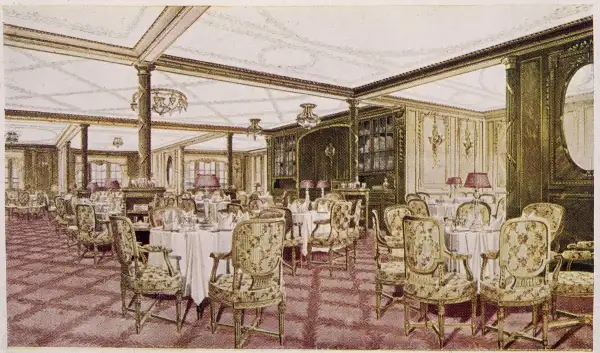

At meal times, the Cardezas would have had their choice of the first-class dining room or the privately owned a la carte restaurant, which charged extra. Few menus survive, but one from the dining room’s final meal shows that patrons enjoyed a dinner of 10 courses.

If first-class passengers had any doubts about their place in the food chain, the menu would have reassured them. The courses included oysters, salmon, chicken, lamb, duckling, and squab, plus two offerings of cow (filet mignon Lili in the fourth course, sirloin of beef in the fifth).

After dinner, Thomas might have headed to the first-class smoking room, a male-only bastion. Charlotte could have retired to the first-class lounge, a popular venue for card playing and conversation, with decorations modeled after Versailles.

If the Cardezas regretted that extra helping of, say, pate de foie gras or peaches in Chartreuse jelly, they might have planned a next-day visit to the salt-water pool, the Turkish bath, the squash court, or the gymnasium. The last was equipped with the latest exercise machines of the day including both an electric horse and an electric camel.

Whether or not their wealth had anything to do with it, both Cardezas and their servants found seats in a lifeboat on the Titanic’s last night, unlike 1,500 other people who were either trapped on the ship or bobbed in the 28 degrees Fahrenheit waters until overcome by hypothermia.

They did have to leave those 14 trunks and other baggage behind. Months later, when Charlotte Cardeza filed a claim against the Titanic’s owners, the list of her lost dresses, furs, jewelry, and other possessions ran on for 16 single-spaced typed pages—a testament not only to her spending power but to what must have been a remarkable memory.

Included on the list was $5,500 in 1912 cash, the equivalent of $132,000 today. But that was small change compared with her total claim, which she valued at more than $177,000—or $4.2 million in 2016 dollars. (You can read the claim in its fascinating entirety online, courtesy of the National Archives.)

Unlike many less-affluent passengers and crew members, the Cardezas were hardly impoverished by the disaster. Both continued to live in the style to which they were accustomed until her death in 1939 and his in 1952.