2020 Finally Broke the Unemployment Safety Net. Now What?

When this is all over, it may be tempting to frame the trauma COVID-19 has inflicted on the U.S. workforce as a tragic, yet inescapable consequence of the public health crisis upending our lives.

Donisa Robinson, a 51-year-old chef who lost her job at the Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) in March, knows better.

From her work station behind the Terminal B sushi counter, Robinson saw the pace of the economic slowdown first hand. Flights from China started getting canceled back in January, she remembers, and the airport’s slowing stream of domestic travelers tapered off soon after.

So it wasn’t a huge shock when HMSHost, the concessions conglomerate that owns her old restaurant, gave her a pink slip. In her mind, the company “should have been putting plans in place,” to prepare Robinson and her laid-off coworkers for the worst; seeing as it applied for —and received—millions in rent relief from local governments nationwide.

"That's a cold piece of work," she says. "We were on the front line. And we got no kind of nothin.'" (HMSHost did not respond to a request for comment.)

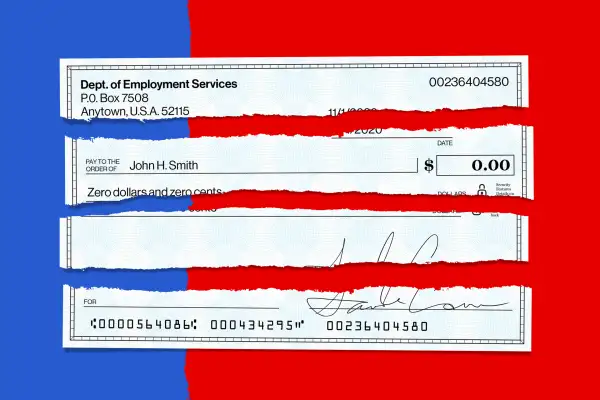

As if there wasn’t enough salt in the wound already, the state of California says Robinson is entitled to $368 in unemployment insurance (UI) every week; a mind-boggling sum in a city where the monthly rent alone averages more than $2,500.

Each $600 weekly payment Robinson got from the CARES Act was a lifeline, but those checks dried up months ago. She’s doing what she can to avoid losing her home—selling homemade cocktails for cash, inviting her son and sister to move in and help with the rent—while applying to every job she can. But she’s an hourly employee in an industry that struggles to take care of its own even in the best of times. And this is not one of those times.

Eight months into the Coronavirus pandemic, the Trump administration is doubling down on the claim that the economy is rebounding “very, very strongly.” For workers like Robinson, that couldn’t be further from the truth.

New research from Columbia University shows that the U.S. poverty rate was higher in September than in April or May, when nationwide shutdowns locked people in their homes and disconnected large swaths of workers from the labor force. The effects have been particularly severe for Black and Hispanic people, who, historically, are twice as likely to be unemployed as white people. And a new analysis by Money shows that unemployment insurance doesn't cover basic costs of living in most states.

Even if Congress successfully passes the second stimulus package it’s been batting around for weeks, bureaucratic red tape and eligibility gaps will keep many Americans from getting the help they need.

The trouble lies in a mishmash of factors that reinforce America’s worsening wealth gap: Tax policies skewed in favor of employers, shareholder influence, a hiring culture that discourages upward mobility.

Underscoring all of this is an unemployment insurance system that doesn’t always work for the unemployed. This has been true for years, but in the middle of a pandemic, and our government’s chaotic approach to keeping the economy alive in the depths of it, the system is imploding.

A ticking time bomb

Applying for unemployment benefits in the richest country in the world shouldn't be that hard.

At its most basic, the program is designed to provide temporary benefits to people who lose their jobs “through no fault of their own" (workers who quit voluntarily or get fired for misconduct generally don’t qualify). It’s overseen by the federal government, but paid almost entirely by state taxes levied on employers — each state builds up a trust fund to fall back on in lean times, when unemployment is high, and to replenish during periods of economic growth.

That’s the idea, anyway.

Many states have opted to keep the tax burden on businesses as low as possible, effectively drying up the reserve money needed to pay out UI to laid-off employees. Over the last eight years, states have been steadily decreasing the amount of UI taxes they collect from employers, despite warnings from the federal government to do the opposite.

In Texas, the average employer UI tax rate is 1.14%, the lowest it’s been in 11 years. California hasn’t increased its “taxable wage base,” the maximum amount a company can owe for each employee, since 1983. It currently sits at $7,000 — by comparison, the state's West Coast neighbors have taxable wage bases more than five times that amount: Oregon’s is $40,600; Washington’s is $52,700.

Instead of raising taxes on businesses after the 2008 recession, 10 states cut the number of benefit weeks people can apply for. (In Florida and North Carolina, benefits max out at just 12 weeks.) The UI tax burden is still so small for U.S. companies that for every one dollar that was collected in 2019, $.81 went to paying back money states borrowed to cover claims from the previous year, according to data from the Department of Labor (DOL).

That means less money for people who lose their jobs, and more hoops to jump through to qualify for it.

“The system is under-funded in many states,” says Till von Wachter, a professor of economics at U.C.L.A. “If you're constantly worried that the system is underfunded, you don’t have a big incentive to get a lot of people in it."

That wasn't always the case.

Unemployment insurance was first pitched as a life raft for people recovering from the Great Depression — regulators added it to the Social Security Act of 1935 as a means to “offer protection against many of the major hazards of modern economic society.” But by many counts, the program has actually gotten less generous as it's aged.

For one, UI started out as a tax-free source of income, making every check worth about 15% to 20% more than those issued today, says Gary Burtless, a senior fellow of economic studies at the Brookings Institution.

Also, back when UI was designed, paying for healthcare didn’t require a full-time job. Medical costs are one of the most expensive aspects of modern life, and can be especially onerous if you’re between jobs and aren’t on an employer-sponsored health plan. According to a report from the Kaiser Family Foundation, the average family health insurance plan costs nearly $1,800 a month — a financial burden most unemployed people have to shoulder themselves.

“That’s a pretty big share of compensation that’s not replaced by the UI system,” Burtless says.

Overall, he says, “The protection you receive from UI benefits has gone down. That means a lot of the unemployed are definitely worse off.”

UI checks themselves haven’t gotten any more robust over the years. On December 31, 2009, the average weekly benefit amount was $308.73, according to data from the Department of Labor. Ten years later (a month before COVID-19 hit the U.S.), it sat at $368.97. Accounting for inflation (“2009 dollars”) drops that number to $309.97 — just $1.24 more than the average weekly payment a decade prior.

Nationally, unemployment insurance is far removed from what people need. And employers aren't making things any easier.

Juan Giraldo, a 40-year-old resident of Los Angeles, California, says he had to rely on credit cards to cover his bills, and food banks to feed his family, after his unemployment claim got denied in April.

Giraldo drives a port truck up and down the California coast. Like Donisa Robinson and her airport colleagues, his industry was one of the first to be impacted by the pandemic — by spring, Giraldo's workload had already been reduced by about 80%, he says, and his company contract forbids him from applying elsewhere.

The company Giraldo works for claims he’s an independent contractor, a designation that disqualifies drivers like him from receiving traditional unemployment insurance. Labor advocacy groups say this is a misclassification that saves the port trucking industry an estimated $1.4 billion in UI tax and wage violations, and have won several class-action lawsuits over the distinction. (Over in Silicon Valley, companies like Uber, Lyft, and DoorDash are currently financing the most expensive proposition in California's history for the right to keep labeling drivers as "contractors.")

After months of back and forth, California’s Employment Development Department (EDD) determined that Giraldo was, indeed, an employee, and approved him for UI. This is a pervasive issue among truck drivers, he says. But many are too afraid of employer retaliation to speak up.

“It’s really denigrating,” he says. “They’re taking from us ... the opportunity to have a better life.”

The explosion

It’s hard to articulate just how ill-equipped unemployment offices were at managing the onslaught of UI applicants they were bombarded with this spring when, all over the country—in places as disparate as Camden, New Jersey, and Anchorage, Alaska—some 23 million people were suddenly out of a paycheck.

Federal aid outlined in the CARES Act helped more people qualify, like freelancers, recent college graduates, and applicants with patchy employment histories. And everyone who qualified for UI got that extra $600 a week through the end of July. (For a few weeks after that, President Trump tapped FEMA funds to provide some applicants with another $300 a week.)

But not everyone qualified.

In March, less than 15% of unemployed people received benefits in 10 states, according to the Pew Research Center.

For the other 85%, a chain of near-insurmountable hurdles stands in the way of government aid. Maybe their employer misclassified them as contractors, as Juan alleges his has. Maybe they work off-the-books jobs in child care, cleaning, or hospitality. Or exhausted their unemployment benefits before the pandemic even hit. Maybe they’re immigrants, homeless, or live in one of the rural or tribal patches of the country without reliable internet access. Maybe they don’t even know UI exists — in the emergency form that the CARES Act put forth or otherwise.

To make matters infinitely worse, many states lacked the infrastructure necessary to quickly dole out aid to those who were approved. In September, 60% of the people who received their first benefit payment in Kentucky had waited longer than 70 days to receive it, according to DOL data. Others are still waiting: As of this writing, Oregon owes “hundreds of millions of dollars” to laid-off residents, and representatives don’t expect that to change before the end of November, according to The Oregonian.

Even states like Nevada, which took steps to aggressively restore them after the last recession, are approaching dire straits.

“The scale of this is completely unlike anything we’ve seen,” says David Schmidt, Nevada’s Chief Economist. “In the first week of business shutdowns in the state, we took more than ten times more claims than the worst week we’ve ever had. This is something you’ll never find precedent for, ever.”

In other words: losing your income in 2020 is a brand new—and uniquely vile—circle of hell.

Just ask Mohamed Jama, a 38-year-old Uber and Lyft driver in Seattle, who says he gets less than a quarter of his regular salary in UI benefits. For two months, Jama says, he didn’t get anything at all.

Every time Jama logged into Washington’s UI portal to see where the money was, it showed his payments as “pending,” he says. Attempts to sort out the issue his local unemployment office’s jammed phone line got him nowhere.

“They would say, ‘at least you’re getting paid. Some people are getting nothing,’” he says.

Jama lives with his grandpa, who’s in poor health, and the thought of passing along COVID-19 to him scares Jama to death. He’s done his best to avoid contact with the outside world, but to keep a roof over both of their heads, Jama will need to start driving again soon.

When we spoke in early October, his UI checks had once again stopped coming.

This isn’t an isolated incident. Social media is filled with people begging for clarity on why they still, after all this time, haven’t received aid. Others want answers to a long list of contradictions the system has unearthed. Why is answering one confusing question on your UI application preventing so many people from getting benefits? How can the government figure out how to quickly disperse billions of dollars to American businesses, but not its citizens? If Trump has “created more jobs” than any other president, and the U.S. is “rounding the corner” on Coronavirus, two claims the president has been shouting from the rooftops, why can't they find work?

In early October, the same week Trump ordered aides to stop negotiating with Democrats on another stimulus package, the top post on the subreddit r/unemployment was just a long list of suicide hotlines.

“It’s like we’re pawns,” says Jake Wells, a Brooklyn, NY-based actor and filmmaker.

Wells posted on the r/unemployment Reddit in September with a heartwrenching story about a friend who committed suicide a few days prior, after learning that a furlough from a department store had turned into a permanent layoff.

He's trying to stay positive, and says he went on Reddit to encourage people to do the same. Wells had to navigate the UI system himself this summer, but was able to come off of it when he started booking gigs again.

“Obviously, I’m one of the lucky ones,” he says. “Nothing about this system encourages anything better for people."

The aftermath

When Alex Trujillo, a 24-year-old coffee shop manager living in California, decided to move back home to Washington, D.C. this spring, things went surprisingly smoothly.

Trujillo is a salaried employee at a bougie coastal coffee chain, so they basically just transferred from one location to another. (Trujillo uses they/them pronouns.)

Their parents, on the other hand, may as well have been living on a different planet.

Trujillo's mom and dad have been working in the D.C. restaurant industry since they moved from Mexico nearly 20 years ago. The couple lives with their 23-year-old and 10-year-old sons, and it’s been close to six months since anyone in the house got a paycheck. They aren’t U.S. citizens, so they don't qualify for government aid.

Finding the resources to cover the entire family’s rent, utility, and healthcare bills is now a constant stressor, and Trujillo moved across the country to help them figure it out.

Recently, however, Trujillo has received some unexpected help. Local food banks have kept the family’s fridge stocked, and a social worker has helped them avoid eviction. After Trujillo set up a GoFundMe campaign, the family was able to pay some of the bills they’d fallen behind on.

“They’ve never had to worry about their next meal,” Trujillo says.

The U.S. response to COVID-19 has been a disaster by many yardsticks. But if there’s a silver lining to the cloud cast by months and months of bureaucratic incompetence, it’s that, at a time when millions of families are feeling abandoned by their government, their neighbors are stepping in.

Mutual aid groups have sprung up in every U.S. metropolitan area to deliver groceries and medical supplies to underserved communities. When Disney announced it was furloughing—and then laying off—28,000 “cast members,” one employee launched a food pantry out of her garage for those impacted. On Reddit and Facebook, strangers are helping diabetics get insulin, parents get diapers, and job seekers get gas money.

In the coming months, this kind of support will be vitally important.

By early 2021, many out-of-work Americans will have fallen into “long-term unemployment,” the point where their benefits typically run out, and their odds of getting back into the workforce slims. Communities of color will be hit hardest: Research shows that Black workers are often the first to get fired during downturns and the last to get rehired when the economy rebounds.

“People that will reach the point of long term unemployment at certain points over the next 10 or so months … can easily dwarf the highest numbers we had during the great recession,” says Joseph Carbone, president of jobs development group The Workplace. “And that makes me sleepless.”

Many of the jobs that have been lost to the pandemic will never come back, Carbone says. Restaurants will shift to take-out only, or close permanently. Retail shops will go online. Parents will decide to work remotely—or keep working remotely—instead of paying for a nanny.

These are the jobs that can’t be done over Zoom, and more often than not, are filled by people who can’t afford to lose them.

Mohammed Jama, the cab driver, is weighing the pros and cons of sleeping in his Prius. Chef Donisa Robinson has over 30 years of professional experience — but can’t get a callback to save her life. Jake Wells is drafting lengthy Reddit posts to keep strangers from hurting themselves.

For many Americans, our broken unemployment system has made weathering a job loss practically unbearable, even in the best of times. And this is not one of those times.

More From Money:

Unemployment Benefits Fail to Cover Basic Living Expenses in Most States, a Money Analysis Finds

The Best Life Insurance of 2020

How to Apply for Unemployment Benefits and Get the Most Money