What My Music Teacher Taught Me About Money

After I delivered my most recent book, a former colleague asked if I'd be interested in filling in as a reporter at my local newspaper. Assignments included writing about puppies being reunited with their mother - literally a fluff piece - and it wasn’t how I wanted to spend my time.

It's not that I felt above it. But it wasn't part of the plan. I was an author now. But I thought about the regular paychecks, my non-existent savings account and the family of four I support. And I started thinking about a lesson I had learned decades ago as a young musician: If you don't want to do it, you probably should.

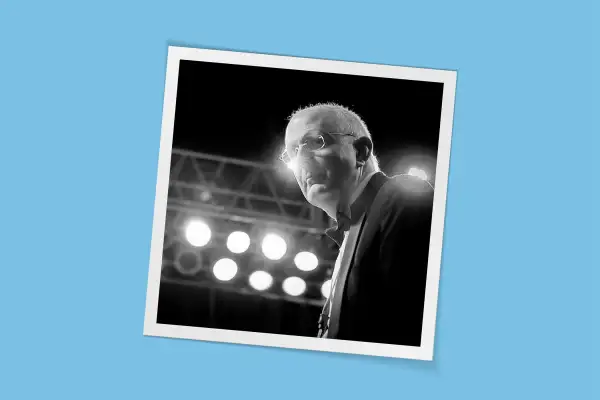

I first met Dan Bukvich, the director of the University of Idaho's jazz choir, the summer before I entered eighth grade. Standing on the main floor of one of the university's dorms, I asked a counselor at its summer music camp which of the optional classes I should sign up for. He suggested “Rhythm, Rhythm, Rhythm.” He wasn't sure what the class entailed, but the syllabus was immaterial. All that mattered was that it was taught by Bukvich.

When I entered my freshman year at the university and started taking percussion ensemble, jazz choir, private drum lessons, music theory and the appropriately titled DancersDrummersDreamers from Bukvich, the message became even more clear. It didn't mater what class Bukvich taught, he was always teaching the same thing. They were all vessels and excuses on which to impart his lessons.

Looking back, he was teaching more than how to sing the correct bass part to the Beach Boys' “In My Room.” He got that few of his charges would be singing for a living. So, he taught something bigger. During those years in school, he was teaching us how to be professionals and, for lack of a better word, adults.

“Don't let someone else ruin your experience!” he'd holler. (In a choir with 200 voices, there was ample opportunity to point fingers.) “If you don't want to do it, you probably should,” he'd say when the suggestion came up during music theory that copying rhythms was below our intellect. I'll never forget his most famous lesson, the one they're going to chisel onto his tombstone: “If you can't get out of it, get into it.”

He got that every job – whether it's singing in a band or pushing paper behind a desk – came with mundanities and frustrations. But they are inescapable. Since they could not be avoided, he taught us to embrace them.

He was right about all of it, of course.

At these temporary jobs, I'm surrounded by smart people who have different skills, goals and perspectives than I do. They think differently than I do. And they think about different things. Working with them on projects seemingly unrelated to my primary hustle, the circles in my professional world's Venn diagram invariably overlap.

Sure, there are also the classic office minutiae – assets, deliverables and conference rooms. Through those, Bukvich is the angel on my shoulder with the perfect backbeat, reminding me during long, boring meetings not to waste these prescribed breaks, but to mine them for inspiration and some much-needed extra cash. There have been other “interruptions” to my “plan,”of course. I often get into them for the money, but I get far more out of them.

Chris Kornelis's latest book is Rocking Fatherhood: The Dad-to-Be's Guide to Staying Cool