Your Brain Does Really Weird Stuff When It Thinks About Money

Money is an emotional topic, which partly explains why we all struggle to spend, save, and negotiate in an optimally rational way. But what's really happening inside our brains when money comes up?

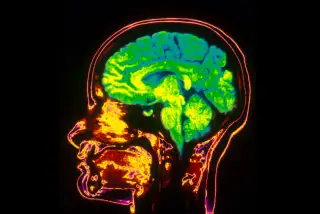

Well, a Harvard Business Review article by author Kabir Sehgal looked for answers to that question by breaking down some of the most important money-related fMRI studies of the past two decades. The answer, in short, is a whole lot.

Here are three of the key takeaways:

That stomach pain you feel when your money is at risk is real.

In one 2003 study, test subjects were asked to play a game known among behavioral economists as the "Ultimatum Game": a pair of strangers are given a sum of money and asked to split it. One person acts as the "proposer," the other as the "responder." If the pair can't agree on a split, no one walks away with cash.

Not only did "responders" turn down more than 50% of unfair offers (an irrational choice, given that something is better than nothing), but the study found that such offers activated a part of the brain associated with anxiety, pain, and hunger. That part of the brain even has so-called spindle cells—a type of cell primarily found in the digestive system.

As Jason Zweig writes in his 2008 book Your Money and Your Brain, “When you get a ‘gut feeling’ that an investment has gone sour, you might not be imagining. The spindle cells in your insula may be firing in sync with your churning stomach.”

Your brain making money looks a lot like your brain on cocaine.

In 1997, a study put brain scans of cocaine addicts high on their drug of choice next to brain scans of non-addicts playing a money game in which they had the potential to win or lose cash.

What it found was striking: Game-players who were about to make money displayed heightened brain activation in the nucleus accumbens, a part of the brain tied to reward, pleasure, motivation, and addiction. The brain scans of addicts high on cocaine were almost indistinguishable.

So when people say money is a drug, they may not be far off.

Risky decisions and safe decisions happen in a different part of the brain.

In a third study—this one in 2005—researchers used fMRIs to monitor the brain activity of participants as they chose between stocks and bonds based on a small amount of information about the performance of each.

Participants were prone to two types of investing mistakes: risk-seeking mistakes (going for the stock when it was unwise) and risk-aversion mistakes (going for the bond when a stock would have been more promising). And in the brain, the two looked completely different.

Whereas risk-seeking mistakes were associated with high activation of the nucleus accumbens, risk-aversion mistakes were linked to activation of the anterior insula, a hub of social emotions and self-awareness which other studies have found lights up when people "feel pain, anticipate pain, empathize with others...see disgust on someone’s face...[and] decide not to buy an item."