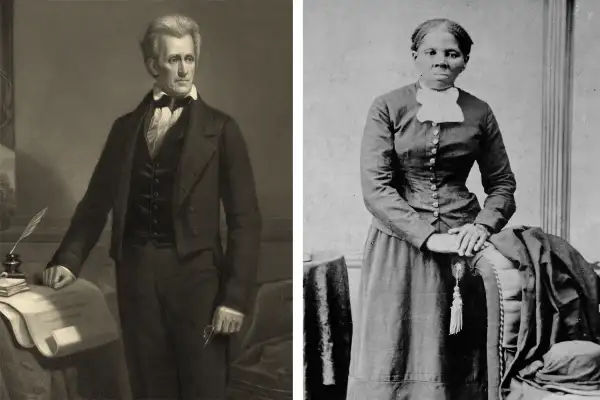

Let's Admit It's Weird Harriet Tubman and Andrew Jackson Will Share the $20 Bill

Yesterday, the Treasury Department gave feminists everywhere something of a surprise victory when Secretary Jack Lew announced abolitionist trail-blazer Harriet Tubman will replace former president Andrew Jackson on the face of the $20 bill.

Last we heard, a woman was set to replace Alexander Hamilton on the $10 bill. Then, Hamilton-mania struck, thanks in part to the eponymous Broadway musical, and suddenly the Founding Father was staying put; a woman, it was reported, would move to the back (talk about symbolism).

Many had suggested that instead of dumping Hamilton, the Treasury should boot Jackson, a slave owner and trader and noted opponent to the national banking system, on the $20. But there was no indication until Lew's announcement that that was even option. So it was a pleasant surprise.

Lew also announced that Lucretia Mott, Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Alice Paul would be featured on the backside of the re-designed $10 bill, another victory for people who championed putting more women on the bills.

But lost in the excitement of the announcement was the fact that while Tubman would indeed be replacing Jackson on the front, Jackson wasn't completely disappearing. He's instead staying on the $20—on the back of the bill.

In other words, the new $20 will feature a former slave and hero abolitionist on one side, and a slave owner on the other. Does that seem a bit tone deaf to anyone?

Jackson owned hundreds of slaves in his lifetime, and built his wealth off of their labor on his plantation. Not to mention, he also engineered the genocide of thousands of Native Americans through the Indian Removal Act and the Trail of Tears.

Tubman, meanwhile, devoted her life to fighting injustice, escaping slavery and returning to help dozens more of her family members, fighting for women's suffrage, spying for the Union, and much more.

Again, a former slave who helped save the lives of an untold number of other slaves on one side, the man behind the forced removal and resultant deaths of thousands of Native Americans on the other? A man who built his wealth off of what the woman fought her entire life against, on money, together? That's a lot of layered meaning to unpack.

Read Next: It Could Be a Decade Before You Hold a Harriet Tubman $20 Bill In Your Hand

There are many reasons to celebrate that Tubman's visage will soon be on our currency. Besides being the first woman in over a century to grace a paper note, she will be the first African American to do so. Her representation will equate the accomplishments of a black woman with those of white men, a symbol of worth and equality that's long overdue.

But it will also be a reminder that America was built on the backs of enslaved people who gave their bodies and their lives to a system that counted them as property, unable to acquire themselves the money that their owners earned off of their labor. (Never mind the fact that a woman still won't be featured on a bill by herself. George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, Benjamin Franklin—they're all the sole proprietors of their currency. I guess it was too much to ask that a woman be given the same honor.)

Though, in a country still grappling with the legacy of the racism engrained in it from the beginning, perhaps there's no better representation of what we've been and what we aim to be than the uncomfortable juxtaposition of Jackson and Tubman.