How the New Republican Health Bill Fails 'The Jimmy Kimmel Test'

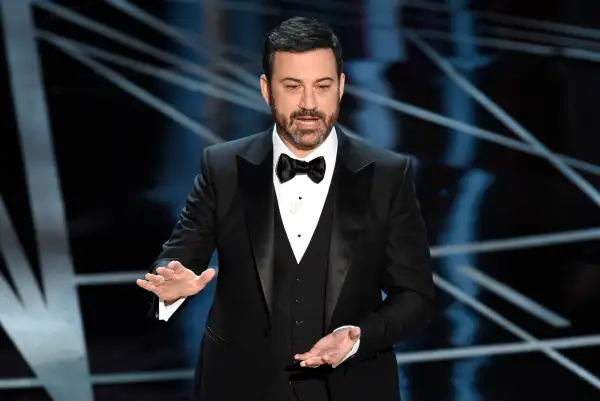

Republicans are staging a last-ditch effort to repeal and replace Obamacare, yet their latest bill fails the “Jimmy Kimmel test,” the comedian said on his show last night.

That phrase was coined this spring by Sen. Bill Cassidy, a Republican from Louisiana and one of the sponsors of the latest repeal-and-replace legislation. Cassidy said at the time that any health care bill lawmakers proposed should make sure that children like Kimmel’s son, who was born with a congenital heart defect, could get all the care they needed in the first year of life.

But Cassidy’s bill doesn’t deliver on that promise, Kimmel said yesterday. GOP senators are attempting to rush a vote on their legislation by Sept. 30. There hasn’t been public debate on the bill, and the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office has said that its experts won’t have enough time to provide full estimates of the bill’s impact on the deficit, health insurance coverage, or premiums by late next week.

Proponents are counting on this secrecy to move a bill that would do a lot of damage to many, Kimmel said. “They want us to treat it like an iTunes service agreement,” he said. “They’re counting on you to be so overwhelmed with the information that you just trust them to take care of you.”

Last night, Kimmel broke down how the bill fails his test. (Cassidy appeared on CNN Wednesday morning to defend his proposal.)

Just how would it fail the "Jimmy Kimmel test"? Here's three big ways:

1. It would discriminate against people with pre-existing conditions.

The legislation retains the Obamacare provision prohibiting insurers from denying coverage on the individual market to those who are sick or have chronic conditions. However, it would allow states to apply for a waiver allowing insurers to charge people with pre-existing conditions more. Under the bill, someone with asthma in a state that waived protections would face an annual premium surcharge of $4,340, while patients with metastatic cancer would be charged an extra $142,650, according to an analysis by the Center for American Progress.

2. It wouldn’t lower premiums for middle-class families.

Under Obamacare, single people making up to $48,240 and families of four making up to $98,400 receive subsidies from the federal government to lower their monthly insurance premiums. This assistance, which flows directly from the government to the insurance carriers, has helped make coverage affordable for middle-class families. The GOP bill would eliminate these subsidies and replace them with block grants that the states could allocate as they saw fit. “States will be squeezed,” says Dan Mendelson, president of Avalere, a Washington, D.C.-based consulting firm. States that want to maintain robust premium assistance for their residents would likely not have enough money to do so, Mendelson said, and premiums will rise.

3. It could restrict the kind of care that patients receive.

Kimmel expressed concern about the return of lifetime limits, the caps on care that insurers were allowed to impose before Obamacare. A premature baby, or one who needed multiple complex surgeries like Kimmel’s, could blow through a lifetime limit of $1 million in his first year of life.

The provisions in the bill do not explicitly list lifetime or annual limits as one of the insurance market rules that could be waived, says Chris Sloan, senior manager at Avalere. However, he notes, lifetime limits are tied to covered benefits, and states could allow insurers to restrict their list of covered benefits. For example, an insurer could decide to exclude maternity care from standard covered benefits. Patients who wanted that coverage may need to pay much more than for a standard plan—the Center for American Progress report estimates that consumers would pay an extra $17,320 more in premiums for pregnancy. And if a plan excludes a type of treatment altogether, then a lifetime limit wouldn’t even apply.