Here's What Happened to Stocks During Watergate and Other White House Scandals

Money is not a client of any investment adviser featured on this page. The information provided on this page is for educational purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. Money does not offer advisory services.

Stocks are enduring their worst stretch of 2017 as Washington is in the grips of yet another scandal that requires a special prosecutor.

The Dow Jones industrial average tanked more than 370 points Wednesday on news reports that President Trump allegedly asked now-former FBI director James Comey to end the bureau's investigation into former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn and his possible ties to Russian influence.

Those reports — and Trump's firing of Comey last week — sparked an immediate debate about whether the president may have obstructed justice as the FBI investigates whether Russia tried to interfere with the U.S. presidential elections.

The Justice Department has now appointed former FBI Director Robert Mueller as a special prosecutor to investigate whether there was any coordination between Russian officials and Trump campaign associates to interfere in the 2016 elections.

For investors, there are two immediate fears: At the very least, this scandal is sucking all the oxygen out of Washington, making it that much harder for the Trump administration to push its agenda for cutting taxes and stimulating growth through infrastructure spending.

The "markets had risen on the expectation of tax and health reform along with an infrastructure spending plan, but the constant string of high profile distractions involving the president or members of his administration has put all that into jeopardy," said Tom Siomades, head of the Investment Consulting Group of Hartford Funds.

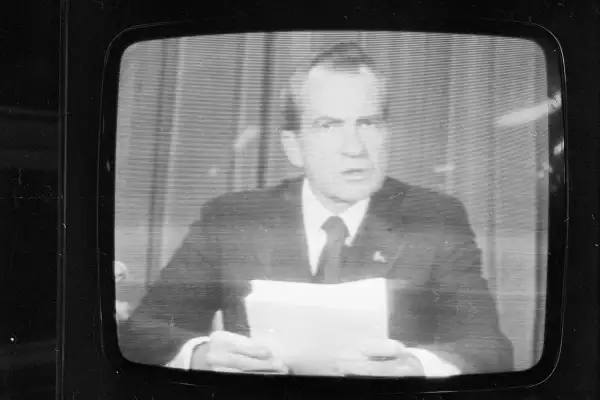

What's more, many "worry that the market will react negatively to the firing of FBI Director Comey, as it did following President Nixon's firing of Archibald Cox, the Watergate special prosecutor, in October 1973," notes Sam Stovall, chief investment strategist for CFRA.

"Investors are now concerned that President Trump will be impeached and are looking warily at historical precedent," Stovall noted.

What does that history show?

Constitutional crises are never good for the stock market. During the Watergate scandal, when Cox was fired and then-Attorney General Elliot Richardson resigned in protest — the S&P 500 fell 14% from October 1st through November.

But investors shouldn't jump to conclusions. Nixon's so-called Saturday Night Massacre took place while Wall Street was already mired in one of the worst bear markets in history. From January 1973 through August 1974 — a period that includes the conviction of the Watergate burglars, Nixon's resignation, global oil shock, Middle East turmoil, and a dramatic spike in inflation — stocks lost 42% of their value.

"[T]he 1973-to-1974 slump seemed endless," Jason Zweig wrote in Money in 1997. "[I]n a crescendo of calamity, war broke out in the Mideast, oil prices quadrupled, Richard Nixon resigned over the Watergate scandal, and inflation hit an annual rate of 12.2%."

Today, Wall Street is in the midst of one of the second-longest bull markets ever. Inflation continues to be muted, and oil prices seem to have stabilized.

This doesn't mean that the stock market is out of the woods just yet.

The S&P 500 fell nearly 20% in the weeks leading up to special prosecutor Kenneth Starr's report on President Clinton, which ultimately resulted in Clinton's impeachment. And that was in the late 1990s, when the stock market and economy were booming.

"However, after investors concluded that this event would not likely lead to recession, the [market] then went on to recover the entire decline and set a new all-time high" at the end of November, says Stovall, months before the Senate acquitted Clinton in February.

"This time around, while the current crisis may trigger a correction, we do not think it will lead to recession and therefore will not result in a new bear market."

Still, that means a correction — defined as a loss of 10% to 20% of the stock market's value — could be lurking around the corner, depending on what the special prosecutor finds.