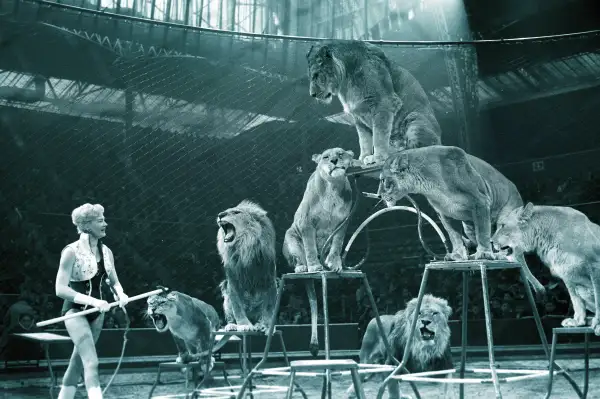

The Lions of Wall Street Are Finally Obeying Ordinary Investors

Money is not a client of any investment adviser featured on this page. The information provided on this page is for educational purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. Money does not offer advisory services.

Even today, a full four years after the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act was signed into law, it remains unclear whether this massive set of financial regulations has made our banking system fundamentally more stable. But one thing about the law is certain: It's gotten the financial industry much more interested in individual investors.

How important have mom and pop become to the titans of capital? On Thursday Morgan Stanley reported second-quarter operating profits jumped by nearly half to $1.3 billion. The biggest contributor wasn’t the bank's investment bankers or traders, but its army of 16,000 financial advisers working with Main Street clients. That didn't happen by chance, either: Chief executive James Gorman, a former management consultant who took over the storied bank in the wake of the financial crisis, has made a point of made a point emphasizing relatively steady activities like wealth management.

That flies in the face of Wall Street tradition. Historically, so-called Masters of the Universe have earned their status advising on giant mergers or trading bonds, which were far sexier (and more profitable) than telling well-to-do lawyers and dentists which stocks to buy. Then the financial crisis hit. Hot-shot bond traders, who once seemed able to conjure millions from thin air, no longer looked so bright. Meanwhile, blockbuster corporate deals that investment bankers specialize in dried up. The economy has finally bounced back. But relatively calm financial markets combined with new regulations like higher capital requirements and the so-called Volcker rule have made it harder for Wall Street trading machines to regain their glory.

That’s given Main Street financial advisers new prestige. It’s not just Morgan Stanley. Big banking firms like UBS and Bank of America, which acquired Merrill Lynch in 2009, have been racing to poach – and keep – top advisers, offering signing bonuses and other perks, even as they’ve sometimes thinned ranks among bankers.

Of course, for you and me, the $10,000 question is not who’s top of the pecking order but whether advisers' new stature will mean better treatment for small investors who, to put it mildly, haven’t always been the Street’s top priority.

In some ways, being a chief profit engine could be a curse more than a blessing. The more banks rely on small investors for profits, the harder they’re going to push to wring every last cent out of their customers. There’s some evidence of this already: While big banks used to be satisfied with handling clients’ investments, they're now leaning on advisers to pitch fee-laden products like loans and credit cards.

The attention that banks give to individual clients hasn’t been evenly distributed, either. Wealthy clients tend to be more profitable. And banks have pushed advisers to focus on these, sometimes at the expense of middle-class investors.

But there’s hope too. On Wall Street profitability eventually becomes clout. Wealth management divisions traditionally haven’t had much. One of the most painful examples: During the financial crisis many small investors got burned after buying instruments known as auction-rate securities, which were supposed to offer the safety of cash but turned out to be illiquid during the crisis. One of the industry’s biggest stars – Smith Barney’s Sallie Krawcheck, then among the highest ranking women on Wall Street – pushed Citigroup to provide restitution to her division’s clients. Instead, she was shown the door. Maybe in the future that sort of thing won’t happen.