Tammie Jo Shults, Who Safely Landed the Deadly Southwest Flight, Has Been Breaking Glass Ceilings for Years

When an engine exploded on Southwest flight 1380 Wednesday, pilot Tammie Jo Shults calmly alerted air traffic control and prepared for an emergency landing in Philadelphia.

"We are single engine," Shults, a former U.S. Navy pilot, said, according to a recording of the correspondence. "Part of it's missing," she added. "They said there's a hole and someone went out."

Shults later landed the Boeing 737-700 jet with one engine and a shattered passenger window, with 144 passengers and five crew members on board. A horrific scene unfolded inside the cabin when the engine explosion blew open a passenger window, partially sucking out the passenger sitting next to it. That passenger later died in a hospital, according to a Philadelphia-based NBC affiliate, and seven others were injured during the ordeal.

As the crisis unfolded in her aircraft's cabin, Shults alerted air traffic control about the "injured passengers" and requested medical professionals to be ready when the plane touched the ground. The National Transportation Safety Board, or NTSB, is currently investigating the event. Shaken passengers later praised Shults as a "hero" for her poise under pressure and her ability to prevent more deaths or injuries.

"This is a true American hero," passenger Diana McBride Self wrote in a post on Facebook. "A huge thank you for her knowledge, guidance and bravery in a traumatic situation. God bless her and all the crew." Self said Shults "personally" spoke to passengers after they landed.

“She has nerves of steel. That lady, I applaud her," passenger Alfred Tumlinson told the Associated Press. "I’m going to send her a Christmas card — I’m going to tell you that — with a gift certificate for getting me on the ground. She was awesome."

In a statement late Tuesday, Shults and Southwest Airlines First Officer Darren Ellisor, one of the other crew members on board flight 1380, said they were “simply doing our jobs.”

“On behalf of the entire Crew, we appreciate the outpouring of support from the public and our coworkers as we all reflect on one family’s profound loss,” the two said in a statement.

When reached by phone Wednesday morning, Shults’ husband, Dean Shults, said they were both unable to comment.

Shults is one of a small percentage of female pilots in the commercial airline industry. Just 6.33% of commercial pilots are women, according to 2016 data from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). And starting at a young age, Shults faced adversity throughout her career as she navigated the male-dominated field.

Here's what to know about the barrier-breaking pilot.

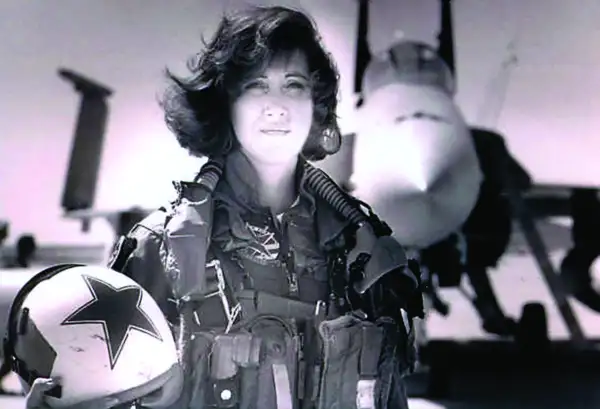

She was one of the Navy's first female fighter pilots

Before she became a Southwest pilot, Shults was one of the first female fighter pilots in the U.S. Navy. Shults initially had limited options in the Navy due to combat exclusion laws that prevented women from flying combat aircraft. But when the law was repealed in 1993, she became one of the first women to fly the Navy's combat jets.

She then learned to fly the F/A-18 Hornet — a newer Navy fighter jet at the time, she wrote in a passage for the book Military Fly Moms, which features insights from female pilots. But she still had to do so in a support role. "Women were new to the Hornet community, and already there were signs of growing pains," she wrote. She struggled with her training unit, she said, due to their lack of "open-mindedness about flying with women." But that mentality was hardly anything new for female pilots at the time.

"Not only is Tammie Jo a great pilot but she is a person of character and integrity," said Linda Maloney, who flew with her in the 1990s in the Navy and who wrote Military Fly Moms, told Money.

"She is one of the best ... personable, warm, caring and just an amazing person," Maloney added.

She faced adversity as a female pilot from the get-go

By even expressing interest in aviation, Shults was met with adversity. As a senior in high school in New Mexico in 1979, she attended a lecture from a retired colonel on aviation as part of a vocational day program, she wrote in Military Fly Moms.

"He started the class by asking me, the only girl in attendance, if I was lost," she wrote. "I mustered up the courage to assure him I was not and that I was interested in flying. He allowed me to stay but assured me there were no professional women pilots."

From there, she struggled to understand her desire to fly, as the field wasn't very accepting of women. She had limited opportunities for most of her career in the Navy before the combat exclusion law was repealed, and she still lands in the minority as part of a small percentage of female pilots for commercial airlines.

"Tammie Jo's professionalism and skill doesn't surprise me at all," Kathryn McCullough, a retired Northwest Airlines captain and member of the International Society of Women Airline Pilots, told Money in an e-mail. "That is what baffles me ... Why don't more airlines want women pilots? We are calm, capable and more than qualified."

The Air Force didn't want her

Indeed, when starting her career, the Air Force "wasn't interested in talking to" her, she wrote in Military Fly Moms. "But they wanted to know if my brother wanted to fly," she noted.

The Navy "was a little more charitable," she said, and allowed her to fill out an application for aviation officer candidate school. It wasn't until a year after she took her Navy aviation exam did she find a recruiter to process her application. "Within two months, I was getting my hair buzzed off and doing pushups in aviation officer candidate school in Pensacola, Florida," she wrote.

Other women inspired her to pursue her goals

While attending MidAmerica Nazarene University in Kansas, Shults found new inspiration to become a pilot. She met a woman who received her Air Force wings, therefore having the ability to operate an Air Force aircraft. "I set to work trying to break into the club," Shults wrote.

In the Navy, Shults worked for Commander Rosemary Mariner, the first female commander of the Point Magu, California-based VAQ-34, a tactical electronic warfare squadron of the U.S. Navy that is no longer active.

"Commander Mariner opened my eyes to the incredible influence of leadership," Shults wrote. "She was a shining example of how to lead."

Shults grew up next to an Air Force base

"Some people grow up around aviation," Shults wrote in her contribution to Maloney's Military Fly Moms. "I grew up under it." She would watch the daily air show as a kid and found the desire to become a pilot herself.

She's married to another pilot

Shults met her husband, Dean, when they both were in the Navy. Calling him her "knight in shining airplane," the couple married just 10 months after they met and both, fortunately, then had orders to transfer to the base in Lemoore, California.

They both left the Navy together in the 1990s to focus on their family life. Now, they have children and are both Southwest pilots.