‘Nobody Cares About Us.’ Federal Contract Workers Who Won’t Get Back Pay Feel Forgotten After Government Shutdown

For Bonita Williams, the partial government shutdown doesn’t feel quite over.

The 56-year-old State Department custodian missed one of her regular $600 paychecks when the department shuttered in December. But, unlike the 800,000 impacted federal employees, Williams can’t depend on any back pay to help clear the stain the shutdown has left. As a federal contractor, she has no guarantee that she will ever get back that missed paycheck, and the financial toll of the longest partial government shutdown in history is just setting in.

She had her car repossessed. She couldn’t afford to buy her grandchildren's favorite lunches and snacks. After missing January rent payments, Williams now worries about the possibility of eviction and is starting to pack her bags for a potential move to North Carolina, where her mother left a home behind.

“The only choice I have is to pack up and try to make it to North Carolina,” Williams, whose son was also put on furlough, says. “I don’t know when my rent office is going to ask me (to leave). I can’t be sitting on the streets.”

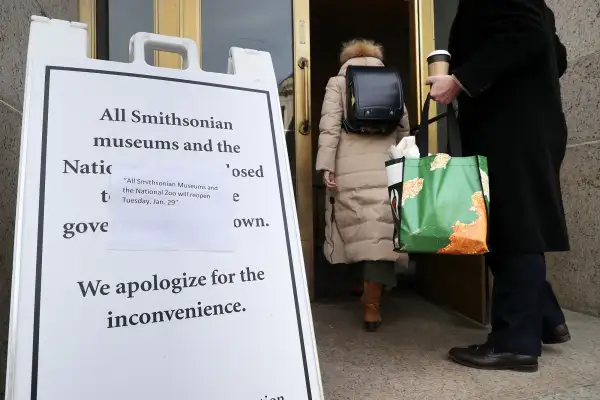

Williams and up to 1 million contractors have found themselves in a state of financial limbo as the government reopens its doors this week. None of these employees — who range from security guards at Smithsonian museums to janitors in the State Department to analysts with other government agencies — are guaranteed any back pay despite involuntarily losing their paychecks. These employees have not received back pay historically, as their paychecks come from the third-party agencies that employ them and not the government itself. But the unprecedented nature of the 35-day shutdown meant it affected more contractors than ever before: As the shutdown grew longer, the number of impacted contractors grew larger as funding lapses hit departments and agencies at different times.

Contractors who spoke with Money since the shutdown came to a close last week say they applied for unemployment and food stamps, took out loans, and dipped into any savings they did have to make ends meet, on top of other personal and financial sacrifices. They say they have been held "hostage" in this shutdown, and worry about what would happen if the government were to shut down again on Feb. 15, after its latest round of funding runs out.

Workers say they also felt hurt that President Donald Trump didn’t mention them in his speech Friday when he thanked 800,000 federal employees and promised them their back pay “very quickly or as soon as possible.” Now, federal contractors not only feel the financial strain of these missed paychecks, but they also feel forgotten.

“I’m not asking for a raise. I’m not asking for a trip to Washington,” says a senior management analysis with the U.S. Customs and Border Protection agency, who asked to remain anonymous out of employment concerns. “It’s horrible to feel like we’re forgotten or that our bills and our lives are less important since we don’t get back pay and they do.”

“We’ve been overlooked like nobody cares about us because we clean,” adds Williams, the State Department custodian. “We are human, too, and we work just as hard as anybody in the federal government.”

The effects of the shutdown continue in different forms as these employees return to work and wait for their next paycheck — without back pay — to come. Loniece Hamilton, a 25-year-old single mother who works security at the Smithsonian's American History Museum in Washington, D.C., used unemployment and food stamps to stay afloat for three weeks without a paycheck. But now she worries about her bills and how she will get to work without any cash in the bank.

“I feel as though we were taken for a joke,” Hamilton says. “I’m just confused. How are we going to get to work with no money?”

Now, federal contractors are fighting for that back pay. A number of federal workers, predominantly those represented by the Service Employees International Union, plan to visit the Capitol on Tuesday to meet with members of Congress about using legislation to compensate these workers. (The Department of Labor, Office of Management and Budget, and the White House did not respond to a request for comment.)

Already, members of Congress have voiced support for providing back pay, and, before the shutdown came to a close, a group of Democratic senators introduced legislation to do just that.

That bill cites the strife of Lila Johnson, a 71-year-old janitor at the Department of Agriculture who missed her biweekly paychecks as a result of the shutdown. To financially bolster her retirement, Johnson has worked part-time at the department to help make ends meet and care for her great-grandchildren. Now, she says she’s behind on everything — car notes, rent, loans, credit card payments — and doesn’t think she’ll get out of this hole until at least March.

“It was a struggle and it still is a struggle,” Johnson, who plans to visit members of Congress to push for this legislation, says. “This money can really get people a little back on track. It would mean a hell of a lot to me to get my back pay.”