'I Knew It Wouldn't Last Long.' What These Former Pro Athletes Can Teach Us About Preparing for Retirement

By the time he was playing his second year in the NFL, Andrew Hawkins was surrounded by Lamborghinis, Ferraris and Bentleys. He decided it was time to buy himself a nice car.

Nothing too flashy, though, maybe a Mercedes or an Audi. Whatever it was would be an upgrade from the used 2005 Chevy Impala he bought in college.

During a practice break at a Cincinnati Bengals training facility in 2012, he was scrolling through car models on his phone when Mike Brown, the billionaire owner of the Bengals, pulled into the parking lot. He was driving a late model Chevy Impala, practically identical to Hawkins’ — but Brown didn’t even have the CD player.

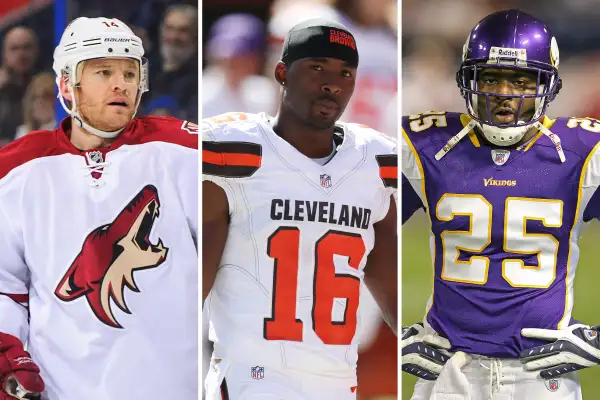

“It was a wake up call for me,” Hawkins, who retired from the NFL in 2017, tells Money. (He also played for the Cleveland Browns, among others, and signed with the New England Patriots.) “I thought, ‘this is the richest guy in the entire city, he’s a billionaire. If he’s got my car, I’m good.’ Hawkins waited another five years before buying the Mercedes he’s still driving today.

Professional athletes have much shorter careers than average workers, so they need to learn their money lessons fast. They also face the challenge of earning large sums of money at a young age, which is just one of many factors contributing to the staggering statistic that 78% of NFL players either go bankrupt or are under financial stress within two years of retirement.

Still, avoiding financial duress in retirement is something all Americans can relate to — after all, the majority of people 65 and older rely on Social Security as their main source of income. Staying financially healthy as you get older comes from following the same core principles, whether you're running for a first down or climbing the management ranks at a corporate job. Here's what athletes can teach the rest of us about getting your finances together and preparing for retirement.

Live Beneath Your Means

Hawkins was lucky to learn about the financial side of his career from his older brother who previously played in the NFL. Many athletes have little-to-no experience managing their finances being drafted straight out of college in their twenties, and don’t necessarily have exposure to others who do either.

It may seem — to the athletes themselves at first and to the general public — that they make a ton of money (and to be sure, some really do). The average salary across all sports for a professional athlete is around $1.9 million, according to Frank Zecca, managing director of wealth management company Octagon Financial Services (OFS), which specializes in managing athlete and celebrity wealth. But after paying your taxes, your agent, your financial advisor, helping family and friends, and maintaining a certain lifestyle, you’re often left with much less than Lamborghini money.

"The money seems easy because you can’t spend it as fast as it's coming in," Hawkins says. "But for a guy who gets his first big contract at 27, it took you 27 years to make that money. Take the time to figure out how to set yourself up financially.”

Hawkins waited to buy his Mercedes until he had his nest egg secured after receiving a signing bonus in his late 20s. Despite cashing a seven-figure check, he still made himself live below his means, a financial golden rule most Americans, athletes or not, struggle to live by.

The NFL has one of the best 401(k) programs out there, with a two-to-one match. Hawkins told his fellow footballer players to max out their retirement accounts immediately (something we should all do).

“It’s free money,” he says. “The young guys say ‘they’re taking my money,’ and I say 'no, this is free money, you’re just giving yourself extra money later on.'” Most American workers aren't contributing enough to their 401(k)s, with the average retirement account balance hovering at just $95,600, according to a report from Fidelity, despite the fact that financial advisors say you need a minimum of 10 times your annual salary saved up to live comfortably in retirement.

Contributing to 401(k)s and IRAs may be less sexy than getting in early on an IPO, but they offer more security since the IRS imposes a penalty in most cases if you access them before age 59½, mitigating the common temptation to dip into your savings when you want to splurge — a tendency that is heightened when you're expected to show up at fancy dinners and wear expensive clothes, a lifestyle that is hard to avoid when you’re in the spotlight.

“In college, you go to Olive Garden because it’s all you can eat for $7.99 on Wednesday nights, then all of sudden you’re in the NHL and you’re going to top of the line steakhouses throwing down a lot of money at the end of the dinner with everyone,” Jeff Halpern, retired NHL player and current Tampa Bay Lightning assistant coach, says. "Guys get called out for being cheap when it comes to picking up a bar tab, picking up a meal for the trainers, and you don’t want to be that guy. That stuff grows.”

Average Americans also have a habit of ratcheting up their spending when their paychecks grow. Financial pros say that curbing this tendency, known as lifestyle inflation, is key to being able to save enough for retirement.

Four time track and field Olympian Lauryn Williams decided to become a financial advisor when her sports career ended after seeing first-hand the need for athletes to take greater control of their financial lives. You need to take certain steps before jumping into the stock market, she advises, especially given the unpredictable twists and turns athletes' careers can take.

"People see a lot of money and they're like, 'ok how do I invest?'" she says. "I say investing is important but do you have a budget? Do you understand what your monthly cash flow looks like? What do you actually need to live a normal life? Without that in place, you spend a lot more than you need, and saving becomes something you put on the back burner and maybe never happens."

Don't Bank Everything on Future Income

Planning on income you might never have, whether it be from pie-in-the-sky investments or expectations about your career longevity, is one of the financial fumbles that Zecca sees.

“For an athlete, one of the biggest mistakes they can make is planning on non-guaranteed income,” Zecca says. “Saying, 'I’m going spend the first contract and I’m going to save when I get my second contract' — and then those contracts never happen, or someone gets hurt or something goes wrong.”

Athletes need a strong financial foundation early on because they are often at their peak earning years at the beginning of their career, whereas most of us build our earning power over time. College-educated women attain a high salary of $60,000 at 40 years-old and college-educated men realize a high salary of $95,000 at age 49, according to Payscale, whereas the average NFL player is drafted at just 21-years-old.

Although later than athletes', average workers' earning power still peaks earlier than many assume. Financial advisors often refer to the years right before retirement as your "peak earning years" when you should be saving most aggressively for retirement.

But for many workers, this simply isn't the case. Some 56% of workers 50 and older are laid off at least once or leave jobs under financially difficult circumstances, according to an analysis by ProPublica and the Urban Institute. If you wait until your mid-50s to start saving seriously for retirement, you might find that your peak salary has passed you by. Sock away as much as you can before that, even if that means juggling other priorities.

Plan in Advance for Transitions

Spending wisely early on gives you the opportunity to set yourself up with a life after sports, says Clevan “Tank” Williams, who was drafted to the Tennessee Titans in 2002 and retired prematurely in 2009 due to a recurring knee injury after also playing for the Minnesota Vikings and, briefly, the New England Patriots. He now works as an on-air analyst for Yahoo Sports in addition to running his own real estate development business. The same goes for anyone preparing for an encore career.

Once he figured out his career was coming to a close, Williams started taking advantage of the career transition programs offered by the NFL. Players have the opportunity to enroll in short-term programs at prestigious places like Harvard or the University of Pennsylvania to explore their professional interests and make connections in their desired field.

“I naturally gravitated towards real estate,” he says. “I was able to connect with a really great professor at Wharton and basically leverage his network into my Stanford network, and that was how I got my first job after football.” Williams worked for a commercial real estate fund, a competitive field where agents often have to work for a full-year without pay until they close their first deal.

“I had to work for free and show them I was passionate about what I wanted to do,” he says.

He made the smart move to start figuring out his second career while he was still active in the NFL, which allowed him to take advantage of his name recognition and set up meetings with people who otherwise may not have talked to him. Hawkins did the same. (A biopic about Hawkin’s extraordinary hustle to make it to the NFL in the first place starts filming this summer.)

“I would network with as many people as I could while I was in the league,” Hawkins says. “Because people thought it was cool that the starting receiver for the Cleveland Browns was emailing them or giving them a call, so I used that opportunity because I knew it wouldn’t last long.”

Most Americans have to prepare for numerous career adjustments these days, with the average American holding a total of 12 jobs in their lifetime, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Careers experts endorse Hawkins' and Williams' approach: to the extent possible, it's helpful to lay the groundwork for your next job when you're still employed at your prior one. That way, you can test the waters while you still have the security of a regular paycheck coming in. Also, as the athletes' experience suggests, it's easier to network when you're still employed.

Financial security aside, having meaningful ways to spend your time is also paramount after living out your dream on the field or the ice, says Halpern, who played for the Washington Capitals and several other teams and found a secondary career passion in coaching on top of co-founding a fast-casual restaurant business. Having a purpose after sports doesn't just come from work, says Halpern. Many athletes get involved in charity work or working with schools to support children's ambitions.

Halpern was always responsible with money, thanks in part to his accountant mom, and saved from the beginning, knowing that his earning potential would decrease when his playing career ended. Hawkins followed a similar path.

Despite having multiple jobs as on-air talent for ESPN, running his own podcast and working in business development at LeBron James and Maverick Carter's sports media platform, Hawkins still saves consistently and keeps retirement top of mind.

“You can never be too early," he says, "but you can definitely be too late.”

The previous version of this article incorrectly identified Octagon Financial Services (OFS) as Octagon Wealth.