The 2017 MacArthur Fellows Were Just Announced. Here’s How 6 ‘Genius’ Grant Winners Spent Their Life-Changing Prize Money

Jacob Soll has told this story so many times, he almost sounds removed from it.

Not bored, or jaded really. But detached — like it happened to a friend of a friend. Or he read about it in a book, and is a little incredulous.

“It was like Oliver Twist or something,” he says. “I was the lowest paid professor at my university. My roof was falling in, pipes were exploding. When I got the call, I was literally walking to the library in the rain, thinking about how ruined I was.”

It was fall 2011, and the MacArthur Foundation had just named the historian to its fellowship program, an honor that came with a no-strings-attached prize of $500,000 and a mighty boost of career-changing prestige.

Like every good rags to riches story, Soll made a speedy U-turn. The prize, colloquially called a “genius grant,” instantly elevated his professional status. He got a big salary bump, fixed his leaky roof, and threw himself into his work with renewed purpose — selling a proposal for his book on financial accountability, “The Reckoning,” soon after.

“The MacArthur changed everything,” Soll said after returning from a recent meeting with Alexis Tsipras, the prime minister of Greece, on the country’s debt crisis. “Absolutely everything.”

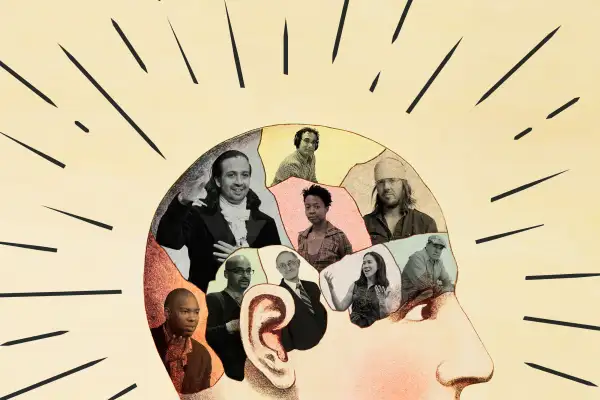

Today, the MacArthur foundation announced its newest batch of fellows — a 24-person list that includes a diverse set of new winners from a variety of different fields. The class of 2017 includes playwright Annie Baker, journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, computer scientist Regina Barzilay, musician Rhiannon Giddens, Pulitzer Prize winning author Viet Thanh Nguyen, and Princeton psychologist Betsy Levy Paluck.

Since 1981, the Chicago-based organization has awarded close to 1,000 of these prizes to a revolving roster of the most influential people in art (Kara Walker, Lin-Manuel Miranda); academia (Amos Tversky, Angela Duckworth); literature (David Foster Wallace, Junot Diaz), and science (Sally Temple, Peter Huybers), among other fields.

Drawn from a foundation started by the philanthropists John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur, the fellowship has changed some in its decades-long tenure (today, it’s worth $625,000, paid out quarterly over a period of five years). But it’s still one of the most notoriously tight-lipped prizes in the world; winners are nominated anonymously by a secret panel of sorts and announced every fall with little fanfare. There’s no splashy awards ceremony or four-course meal. And the driving idea, to give fellows no-strings support to spend their time, money, and mental real estate however they choose, is the same as it’s always been.

This year, though, the prize comes with a little extra oomph.

***

This past spring, President Donald Trump and his administration released their 2018 budget proposal that would make debilitating cuts to federally-funded art, academic, and science programs. Among them: the National Arts and Humanities Endowments, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the Institute of Museum and Library Services, and the National Science Foundation.

With wide swaths of public grant money now facing extinction, competition for private funding will only heat up. And the MacArthur Grant, one of the only no-strings attached prizes in the world, will be more coveted than ever.

“The MacArthur gives you permission to take risks,” says Ruth Behar, a 1988 fellow. “Once you’re blessed in that way, it’s hard to imagine what your life would have been without it.”

Behar, an anthropologist born in Havana and raised in New York, was working on a research project in Mexquitic, a tiny town in Mexico, when she learned she’d won the fellowship. Only one telephone existed there with a notoriously unreliable owner, so it took nearly two weeks to get the news.

When she returned to the United States, her status rose so suddenly and unexpectedly, that a friend compared it to having a long-forgotten book become an overnight best-seller. Within a year, the 32-year-old Behar made tenure at the University of Michigan, where she’d worked for just two years before getting the MacArthur.

A young mother at the time, Behar spent part of her grant supporting her family, and paying for the house in Ann Arbor, Michigan where she and her husband, fellow anthropologist David Frye, live today.

The other portion went directly to her work. Born into a Cuban-Jewish family, Behar began making regular trips to Havana, and writing about the Jewish community there. In the years since, she’s published dozens of articles and a handful of books chronicling the lives of Cuban Jews, a dwindling minority ever since Fidel Castro came to power in 1959.

She had always been interested in the subject matter. But the fellowship gave her the confidence to pursue it.

“I felt like I had won an academic lottery,” she says.

***

There are infinite ways to spend a surprise, no-strings-attached prize. Some MacArthur recipients, like Behar, use theirs to venture into new professional territory. Some, like Gene Luen Yang, a comic book artist and 2016 fellow known for reinventing Superman as a Chinese superhero, use the money for practicalities — bills, college savings, emergency funds.

“If I wanted to, I could buy a Batmobile,” Yang says about the sudden influx of cash. “But I have four kids, so that’s not going to happen.”

On September 29, 2015, the day after Lin-Manuel Miranda was announced as a MacArthur recipient, the Hamilton creator tweeted that he’d “slept in because we paid off my wife's student loans YESTERDAY and we celebrated with wine and backgammon.”

Philip DeVries, an insect ecologist and 1988 fellow, used most of his grant for trips to the field, and a few other miscellaneous items (his first purchase? a pair of red Converse sneakers).

A self-described “plastic bag, notebook, and butterfly net kind of guy,” DeVries discovered “singing caterpillars,” a butterfly species that produces an acoustical call to attract ants, which protect them from predators. His writings on the phenomenon in the early ‘90s continues to guide ecologists’ understanding of insect symbiosis today.

Like many MacArthur fellows, DeVries used the prize as a sort of permission slip to take creative leaps, make mistakes, and experiment without financial restraint.

“No strings attached means you don’t have to report to the National Science Yadda Yadda or the Public Broadcasting Whatever,” he says. “I could go wherever, and do what I wanted.”

Thomas Palaima, an expert on ancient civilizations and a 1985 fellow, used his grant to relocate from New York to Texas, and launch the Aegean Scripts and Prehistory program he leads today at the University of Texas in Austin.

“In 1985, my salary was something like $22,000,” he says. “This totally transformed the state of my career.”

Palaima is concerned about the recent threats to public research grants. It’s never been particularly easy to be an academic living outside major research hubs, but he says funding from sponsors like the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) have helped level the playing field, “where insiderism and domination by the two coasts, plus Chicago and Michigan, was at least in principle neutralized."

Escalating state cuts to higher education have already forced public universities to reduce their curriculums, faculties and research capabilities. When Palaima first took his position, 47% of the school’s operating budget came from government appropriations. This year, it’s down to 12%.

With federal grants and state funding now facing the guillotine, “Of course, we in the humanities and creative arts are worried,” he says.

The MacArthur Foundation, for its part, has a long history of awarding funds to many of the creative efforts with which the Trump administration takes ideological umbrage.

Aside from the fellowship program, the foundation has provided aid to organizations devoted to minimizing climate change, passing criminal justice reform, and supporting investigative journalism.

The foundation, and its fellowship program, are billed as nonpartisan.

“Neither our careful selection process nor the criteria we use (exceptional creativity and potential) change because of elections or politics,” says spokesman Andrew Solomon.

Nevertheless, as public funding becomes increasingly politicized, the grant could be a savior to those caught in the crosshairs. Contributions from past fellows, like 1984’s Frank Sulloway, whose research shaped psychologists’ understanding of the link between birth order and personality, and 1986’s David Page, who went on to map the Y-chromosome, will no doubt loom large.

Environmental engineer Kartik Chandran, a 2015 fellow, may be the next “genius” to follow in those footsteps. Soon, he’ll launch a massive experiment, where Chandran and a group of researchers will live waste-free in a building run by renewable resources. It's an undertaking he hopes will serve as a model for experts working to solve global conservation challenges.

The project comes at a peculiar time for energy research. If passed, the White House budget would cut funding from the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, an agency tasked with moving the U.S. to a clean energy economy, by more than 70%. Just this week, the E.P.A. reversed a key Obama-era policy that worked to reduce the amount of carbon dioxide emitted from power plants.

By comparison, Chandran says the $625,000 he got from the MacArthur foundation, “is all devoted to making this a reality.”

“It’s too early to tell what the magnitude of the cuts will be,” Chandran says of the federal budget. “But in any case, this work cannot stop. We have to keep going.”