The 8 Greatest Political Money Scandals in American History

- 4 Smart Money Moves You Should Make in February

- Money Checklist: 4 Ways to Get Your Financial Life Together in January

- Congressmen to Wells Fargo CEO: Do You Think What You Did Was Criminal?

- Lawsuit Alleges Exactly How Wells Fargo Pushed Employees to Abuse Customers

- How to Get Up to 5% Interest on Savings Even Though the Fed Didn't Raise Rates

As the presidential campaign between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton winds down, we've weathered more than a year of insults, accusations of lying, charges of sexual assault, and allegations of financial impropriety surrounding both candidates.

Trump declared bankruptcy four times, directed more than a quarter of a million dollars from his charitable foundation to settle legal disputes stemming from his personal businesses, used money from the foundation to buy himself an autographed football helmet and commission a painting of himself -- and exploited a tax loophole so “legally dubious” that his lawyers advised him against it.

Meanwhile, repeated questions have been raised about potentially shady actions by the Clinton Foundation, including: How did the Clintons’ charitable work intersect with their for-profit speeches? How did their speeches intersect with Hillary Clinton’s work at the State Department? And did the foundation steer money improperly to friends' companies?

So far, none of these accusations has risen to the level of scandal, but if they did, Trump and Clinton would follow a long line of American political characters with dubious financial dealings.

Here are eight money scandals that outraged the public in their day. Some of the politicians involved were convicted, some leveraged their connections to walk out of court, and in a few cases, corruption didn't stop them from getting reelected or even running for president.

The good news is, those politicians aren't on the ballot this year.

L'Affaire Hamilton

Money scandals emerged early in the nation's history. In fact, Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury, was accused repeatedly of using his power to enrich friends.

Several of Hamilton’s friends and family members were tangled in financial scandals, seeming to provide evidence that Hamilton conspired to enrich them and his party. Little evidence linked Hamilton directly to those scandals. But his affair with a married woman, Maria Reynolds, brought back corruption speculation.

In 1792, Maria’s husband, James Reynolds, who had repeatedly blackmailed Hamilton to keep the affair quiet, was imprisoned on forgery charges. Hamilton refused to “help,” and the husband retaliated by not only leaking the affair but also by lying that Hamilton was his partner in crime.

To clear himself of the corruption scandal, Hamilton admitted the affair.

While the scandal is widely known as a sexual one, (thanks to the Broadway musical), the corruption speculation would haunt Hamilton for the rest of his career -- and impede his ability to bring his economic plans to fruition, says Peter Kastor, history professor at Washington University in St. Louis.

The Whiskey Ring

Hundreds of people -- from government agents and politicians to distillers and distributors -- formed the Whiskey Ring in 1871 to raise campaign funds for President Ulysses Grant's 1872 reelection. They hid the 70-cent-a-gallon whiskey tax and split it among the members. After Grant's reelection, it became a purely commercial undertaking, defrauding the federal treasury through an extensive network of bribes to the tune of $1.5 million a year.

The Ring fell apart after a new Treasury Secretary, Benjamin Bristow, arrived in office in 1874 and began investigating. As prosecutors arrested 300 Whiskey Ring members, Bristow pointed his finger at Orville Babcock, the president's friend and private secretary. Except for him, everyone charged in the whiskey fraud was convicted, but Grant stood by Babcock.

The president ordered a special agent to spy on government prosecutors, issued a policy that eliminated any incentives for people to share evidence against Babcock, and – realizing those weren't sufficient to save him – volunteered to testify for his friend. Ten days after the whiskey case jury found Babcock not guilty, he was indicted in another scandal, but acquitted once more. In 1884, Babcock drowned while serving as the Chief Inspector of Lighthouses.

The Credit Mobilier Scandal

This scandal began with a sham company: Crédit Mobilier was created by Union Pacific Railroad executive Thomas Durant to stash profits by giving work to himself and billing the railroad a price that guaranteed profit. Credit Mobilier not only protected its investors' personal holdings from corporate law, but also ensured payments because the railroad was supported by government bonds.

When Oliver Ames took over Union Pacific's presidency, he and his Congressman brother Oakes Ames introduced the shell company to Capitol Hill. In 1867 alone, Rep. Ames distributed Credit Mobilier stock to two senators and nine representatives, all of whom held positions relevant to the railroad industry, according to a PBS article. After the New York Sun exposed the scandal in 1872, the House investigated and found 14 legislators who received bargain-rate Credit Mobilier shares, including Vice President Schuyler Colfax and then-Rep. James Garfield, who later denied the charges and became president.

The Beloved Governor

In 1934, the federal government convicted North Dakota Gov.William Langer on charges of corruption and forced him to leave office. He had required state employees to donate to his party, and staff in departments funded by federal grant complained.

Instead of stepping down, Langer declared North Dakota independent, instituted martial law and barricaded himself in the governor's mansion until the State Supreme Court would rule on whether he could stay. A small group of cronies joined him for about 10 days, says Kim Porter, history professor at the University of North Dakota.

The court stood by the federal indictment. Amazingly, Langer not only was reelected governor, but also won a seat in the U.S. Senate in 1940 and served until his last breath.

The Senate did question Langer's "moral turpitude" as a public official. A report alleged a chain of shady episodes, including one in 1932 when he kidnapped his client from a local jail, took him to another state and persuaded the client's ex-wife to re-marry the man so she couldn't testify against her husband. The Senate ultimately voted to keep Langer, and paid him $16,500 for defending himself.

Known as "Wild Bill," Langer was largely popular. In fact, farmers marched on the state capitol when the federal government ordered him to leave.

The Teapot Dome Scandal

In April 1922, a front-page story in the Wall Street Journal reported on a contract between the U.S. government and Mammoth Oil to develop the Teapot Dome naval oil reserve in Wyoming. "The arrangement entered into marks one of the greatest petroleum undertakings of the age and signals a notable departure on the part of the government in seeking partnership with private capital," the article said.

Turned out, as revealed by a Senate investigation, Interior Secretary Albert Fall -- who served under President Warren Harding -- accepted $300,000 in government bonds and cash from the president of Mammoth Oil in exchange for the Teapot Dome contract. He was also found to have received a $100,000 "interest-free loan" from the Pan-American Petroleum and Transport Company for another reserve in California. Convicted of bribery, Fall served a year in jail (and became the first former cabinet member convicted of a felony).

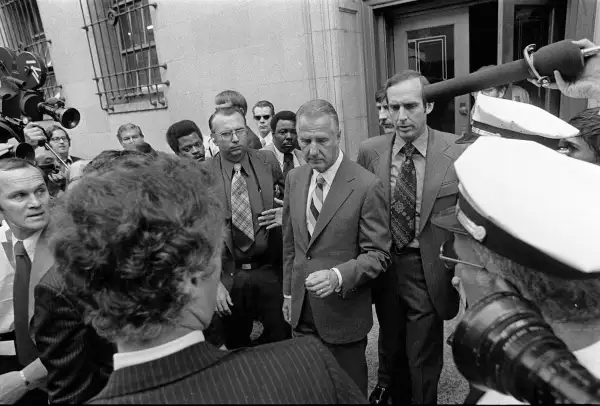

Disgraced Vice President

Less than a year before President Richard Nixon resigned, his vice president, Spiro Agnew, pled guilty to a charge of federal income tax evasion. He became the first U.S. vice president to resign in disgrace.

Nixon wasn't shocked, and argued that in states such as Maryland, where Agnew served as governor before picked as VP, taking campaign contributions from contractors was "a common practice," according to the Senate Historical Office. "Thank God I was never elected governor of California," Nixon joked with his chief of staff H.R. Haldeman.

Even less funny is Nixon's naive belief that Agnew was his insurance against impeachment. No one would want to remove Nixon if Agnew was next in line, right?

The Milk Money Scandal

In December 1973, John Connally was a rising Washington star, President Richard Nixon's Treasury Secretary and a presidential hopeful for 1976.

Yet seven months later, a federal grand jury indicted Connally on charges of perjury and conspiracy to obstruct justice. Prosecutors said the American Milk Producers Inc. bribed Connally with $10,000 to persuade Nixon to pump up milk prices. In 1970, the administration raised milk support prices by 75% to $4.66 per hundredweight and imposed import quotas on ice cream and three other dairy products. An attorney for the American Milk Producers wrote Nixon that the farmers have been in touch with his financial men to set up "appropriate channels to contribute $2 million for your re-election."

Connally ultimately was acquitted. His character witnesses in the 1975 trial included First Ladies Jacqueline Kennedy and Lady Bird Johnson.

The Man Who Bought Washington

Perhaps the largest corruption scandal of our time involved lobbyist Jack Abramoff, who bilked at least $80 million from Indian tribes and bribed his way around Washington. At the height of his success, Abramoff owned two restaurants near the Capitol, bought a fleet of casino boats and leased four arena and stadium skyboxes.

The exact count of legislators who were showered with gifts from Abramoff and jetted off with him golfing in Scotland is still unclear. But as Abramoff pled guilty to charges of corruption and tax offenses in 2006, 10 officials were convicted in the scandal. Former Republican House Majority Leader Tom DeLay was found guilty of money-laundering in 2011, after a 2005 indictment forced him to resign. Then-chairman of the House Administration Committee, Rep. Bob Ney (R-Ohio) resigned after pleading guilty to conspiracy in 2006.