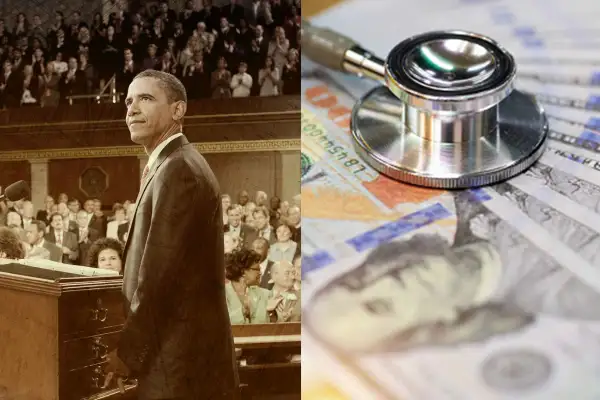

Money Then & Now: The Affordable Care Act and the rising cost of health

We just launched Money Archives, a new experience where we're digitizing decades of our print Money magazines. This is the fifth and final article in a series of stories that examine how personal finance — and our coverage of it — has evolved over time.

Back in 2010, the entire country seemed to be focused on one thing: the enactment of a sweeping and deeply contentious piece of legislation by the name of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, otherwise known as Obamacare.

In the May issue for that year, Money took a deep dive into the intricacies of what became known as the ACA, analyzing its provisions and how it might achieve its ambitious goal of insuring nearly every American.

Before the ACA, an estimated 16% of Americans didn’t have health insurance. Insurers could deny coverage to anyone with a pre-existing condition and had a lot more leeway in canceling someone's plan if they got sick. Insurance companies also had the power to set annual or lifetime limits on how much they would spend on patients.

The law essentially banned those practices. It also expanded Medicaid eligibility, granted tax credits to help pay for premiums and allowed young adults to stay on their parent's plans until age 26. All of this helped slash the uninsured rate, which was 8% in early 2022, a historical low.

But, as we reported in our 2010 story, the ACA did not address some important issues, and the financial burden on patients stemming from high health care costs was chief among them. As we said in our story, "The huge increase in per-person spending on doctors, hospitals and pills'' was directly impacting both the government and people's budgets.

Within the past two decades, health care costs have risen higher and faster than almost any other industry, increasing around 110% since 2000. (Prices for all other consumer goods and services have risen 71% within the same period.) And, while insurance plans will cover a share of these costs, the portion that has to be paid by patients — including premiums, deductibles and even covered medications — can still be unaffordable for many.

The price of health

Cynthia Cox, vice president at the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), a nonprofit health care policy research organization, says that America’s health care system is better off in many ways because of the ACA.

"People have more affordable coverage, and more people are covered,” says Cox. “But we're still, as a society, spending much more on health care than any other country does." said

She notes that one of the main problems is that U.S. hospitals, doctors and pharmaceutical companies charge much higher prices for their services and products.

While most countries can strictly regulate the prices health providers are allowed to charge, there is no such regulation here, and price negotiations between insurance companies and health care providers in the U.S. happen largely behind closed doors.

This can lead to prices varying widely for patients with similar health insurance policies, even within the same hospital. A 2021 report from the New York Times found that a colonoscopy at the University of Mississippi Medical Center cost $2,144 if the patient had an Aetna plan, compared to $1,463 for a Cigna plan and $782 if the individual had no insurance at all.

What we pay out of pocket

Soaring health care costs are certainly reflected in how much customers are paying for health insurance premiums. Take, for example, the monthly premiums for a mid-tier plan for a 40-year-old, which increased from $273 in 2014 to $438 in 2022. Some states have experienced even more drastic changes: In Iowa, for example, the average rose from $253 to $502 in the same time period.

Average monthly premium for a 40-year-old (all states)

| 2014 U.S. average | $273 |

| 2022 U.S. average | $438 |

Average monthly premium for a 40-year-old (Iowa)

| 2014 Iowa average | $253 |

| 2022 Iowa average | $502 |

From its inception, the ACA tried to offset the cost of premiums by providing tax credits, but only to those earning up to four times the federal poverty level. (That would be $54,360 for individuals and $111,000 for a family of four in 2022.) However, making even $10 over that threshold was disqualifying, which meant many middle-class households have not been eligible for a break. "Even if you would have to pay, say, 20% of your income on insurance, there was still no help available for you," mentioned Cox.

The 2021 American Rescue Plan Act (ARP) temporarily suspended that income cutoff so that people earning more than four times the federal poverty level could qualify for assistance. This provision, which capped annual premium spending at no more than 8.5% of one’s income, was extended by the Biden administration through 2025.

When it comes to out-of-pocket expenses, the ACA placed limits on how much a patient must pay under its plans. These limits, however, are high and are set to rise every year. For instance, in 2022, that maximum out-of-pocket maximum is set at $8,700 for an individual and $17,400 for a family. In 2023, that cap will be even higher — $9,100 for an individual and $18,200 for a family.

The ACA and the price of prescriptions

The ACA established that health plans needed to include prescription drug coverage. Under its provisions, insurance companies had to cover at least one drug in each category and class from the official list of approved medications, and pharmaceutical companies had to offer increased rebates to lower the cost of Medicaid-covered drugs.

However, in practice, the cost for the same medication varies significantly between plans and insurers, depending on required co-pays and coverage. And, as the price for prescription drugs rose, the financial burden on patients has increased.

In 2022, Congress passed the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), an attempt at regulating the price of prescription drugs. The law allows the government to negotiate costs for certain Medicare-eligible medications and cap out-of-pocket expenses for seniors. It also requires that companies pay Medicare rebates if they raise the price of their drugs faster than the pace of inflation.

Because of the IRA’s provisions, the Department of Health and Human Services will negotiate prices for 10 drugs in 2023. This number will increase each year until 2029, when 60 drugs will be subject to negotiated prices. While this might seem limited, Cox considers this legislation a meaningful step toward drug price reform, especially since there's been such hesitation to regulate health care prices directly before.

"I think there's starting to be a recognition that that's why our health care system is so unaffordable. It's because we don't have any of that regulation that other countries do," Cox suggested.

"There's an even bigger challenge ahead that the new law only begins to tackle: figuring out how to get a grip on exploding health care costs. This law can't work in the long run otherwise."

As we reported in Money's 2010 breakdown of the law, the price of health care was one problem the ACA did not — or perhaps could not — tackle. Twelve years later, the issue remains.